Donating

Where Does All the Money Go?

For followers of the “Effective Altruism” movement, it’s especially important that donated funds contribute towards measurable success. With this principle, huge achievements are possible even with a small sum of money – if it’s used in the right way. But the concept has also encountered criticism.

By Wolfgang Mulke

Sebastian Schwiecker has never been willing to tolerate the hardship and misery that is rife in many countries. “I have a world improver gene in me,” says co-founder of the charitable giving platform “effektiv-spenden.org”. Hunger and disease, poverty, factory farming and climate change are his adversaries. But simply collecting money and giving it to aid organisations is not in line with his expectations. You see, the economist – an experienced banker and social entrepreneur – aims to achieve the maximum possible effect: Schwiecker is a member of the “Effective Altruism” movement.

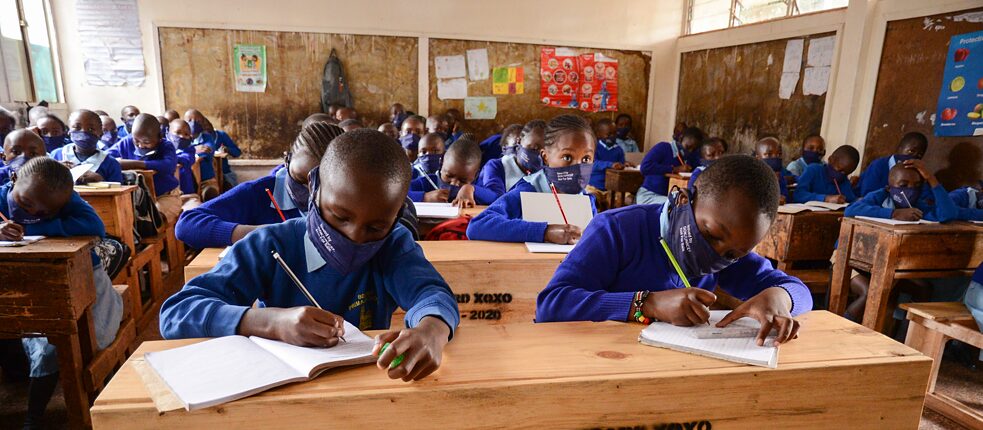

Of course the benefactors want to relieve suffering and improve the world, but not at all costs. The idea is to invest the money or other resources, such as manpower, at the point where they can be most effective. Schwiecker likes to illustrate this with a research paper by Nobel Prize winners Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer on combatting poverty in Kenya. They studied the impact of various methods designed to improve the standard of children’s education. The authors investigated the effect an outlay of 100 dollars has on the regularity of school attendance.

How do you facilitate maximum school attendance on the same budget? A study on tackling poverty in Kenya looked at this question – and returned some surprisingly clear results.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/ZUMAPRESS.com/Dennis Sigwe

How do you facilitate maximum school attendance on the same budget? A study on tackling poverty in Kenya looked at this question – and returned some surprisingly clear results.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/ZUMAPRESS.com/Dennis Sigwe

Pills Instead of Uniform

The result is surprising. If the money is invested in scholarships, children receive around 100 additional days of teaching. A donation for school uniforms allows 260 more days in school, but a health programme to prevent diseases caused by worms facilitates 5000 extra days of education. Effective altruists use research findings like this as a basis for investing their money where it will have most impact.

According to this principle, Effective Altruism follows a cost-benefit calculation that seems more like a business model. The priority is not alleviating individual emergencies, it’s the question of where the available budget can be applied most usefully. Major donors in particular, who contribute portions of their private assets to improve the world, consider it important that the funds are used efficiently. Generally speaking they set themselves a target of donating ten per cent of their income – like the biblical tithe system, according to which the faithful were supposed to give ten per cent of their income to the church.

Individual Cases Don’t Matter

Other aspects of donation come off worse with this model. For example, if there was a choice between funding medicine for a sick child with a specific sum, or using it to finance a project that helps many children in a different way, the individual child would lose out.

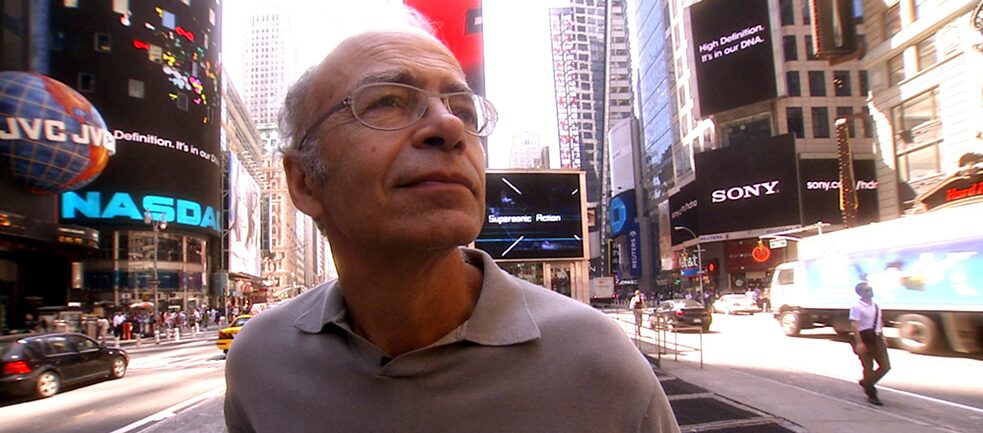

So analysis replaces individual compassion with this approach. Australian philosopher Peter Singer, who places the value of an individual behind that of the situation as a whole, is considered a pioneer in this field. The movement initially took hold in the UK and USA. They collect and evaluate donor data, and analyse organisations and their work in respect to their efficacy. One of the largest rating organisations is GiveWell in the USA, which for instance publishes a list of the top donation opportunities according to efficiency aspects. An in-depth analysis of what aid is possible and necessary is the movement’s main starting point. This is a factor which until now has been insufficiently addressed in the charitable giving sector, even though organisations award themselves a quality seal. “The donation quality mark tends to be more of a protection from dodgy initiatives,” stresses Schwiecker, “but it doesn’t offer much information about the quality of the organisations.”

Widely respected and strongly criticised: public appearances by Australian philosopher Peter Singer often culminate in protests, including by organisations representing people with disabilities.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/Zeitgeist Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

Widely respected and strongly criticised: public appearances by Australian philosopher Peter Singer often culminate in protests, including by organisations representing people with disabilities.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/Zeitgeist Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

Measured Humanity

This calculating philanthropy is also subject to plenty of criticism, for example from human rights organisation Medico International. “Aid like this perpetuates misery, it doesn’t alleviate it,” contends Thomas Gebauer of Medico in criticism of Effective Altruism. He views it as a “questionable cult”, which doesn’t tackle the causes of suffering or aspire to change the underlying conditions in structural terms.

Kai Fischer, a social marketing expert, also believes the approach to be wrong. “It’s true that the right questions are being asked, but the answers are not convincing and they lead in the wrong direction,” he claims. This economic ideology leads to the exclusion of the very people who are particularly disadvantaged, for instance in remote regions, he reckons. Aid in these locations is comparatively expensive to provide and therefore not effective in terms of this movement. “Values are the top priority in the non-profit sector,” argues Fischer – for example physical integrity, medical care and access to culture.

So it’s a little odd that protests keep happening at public appearances by Paul Singer, the pioneer of Effective Altruism – and the protesters include people with disabilities: the fact is that on the basis of a purely quantitative cost-benefit calculation, people with physical or mental disabilities would probably not be entitled to much support – it would simply be too expensive to help them.