Worlds of Homelessness

To live without a keep

These days, it seems that absolutely everyone is being somehow tracked, statistically recorded and entered into spreadsheets of one kind or another. There’s just one group of people that no-one appears interested in: the homeless. Nobody knows how many of them there are, how many new people find themselves living on the streets, how many manage to escape from their homeless plight, and how long they remain without any fixed abode. Gradually, however, interest in this group is growing, and we are beginning to learn more about them and their situation.

By Jutta Allmendinger

This is because homeless people are becoming increasingly visible. Although no concrete figures are available, we have a sense that there are more and more of them. In addition, our stereotypes about homeless people are being shaken up. While in the past we dismissed them as being drug addicts or alcoholics, as mentally ill or criminal – the deserving homeless to use the language of poverty researchers – we are now forced to concede that this is not in fact true. Healthy, honest, and hard-working people in employment can also become homeless. Rapidly rising rents, a declining stock of affordable housing, increasing distances between home and work – sometimes that can be all it takes to make a person homeless. Concerns and fears have shifted from the peripheries of society into the spotlight.

All of these woeful examples make it clear that having a home should be a human right.

In Germany, we are not yet seeing tent cities such as those to be found on the streets of Midtown in Los Angeles. Nor are there any parking garages that remain open at night so that the homeless can sleep in their cars, guarded by security firms and catered for by food trucks. Actually, parking garages are viewed as a privilege, and many simply sleep in cars. Most people in Germany are more than a paycheck away from homelessness, as the saying goes in California. Even the upper middle classes can be heard talking about how close homelessness has become: poor protection against redundancy, little in the way of savings, heavily-mortgaged homes, a lack of social insurance to cover sickness and old age, and no housing allowance. What is more, forced evictions are far easier than in Germany.

All of these woeful examples make it clear that having a home should be a human right. And this means having affordable housing, sufficient incomes, and good local government services. Other steps are also necessary. Investors should be obliged to channel part of the total construction costs into building affordable social housing.

We need more and better accommodation for homeless people; accommodation that is safe and also open to the homeless individual’s partner or pets. The help that is on offer must also be made available to those in gainful employment. “Housing first” schemes that are designed to get homeless people into their own place quickly and unconditionally must be expanded with greater resolve. The public transportation network is particularly important for homeless people and must be extended and maintained. And yes, we need to know a lot more about the homeless themselves.

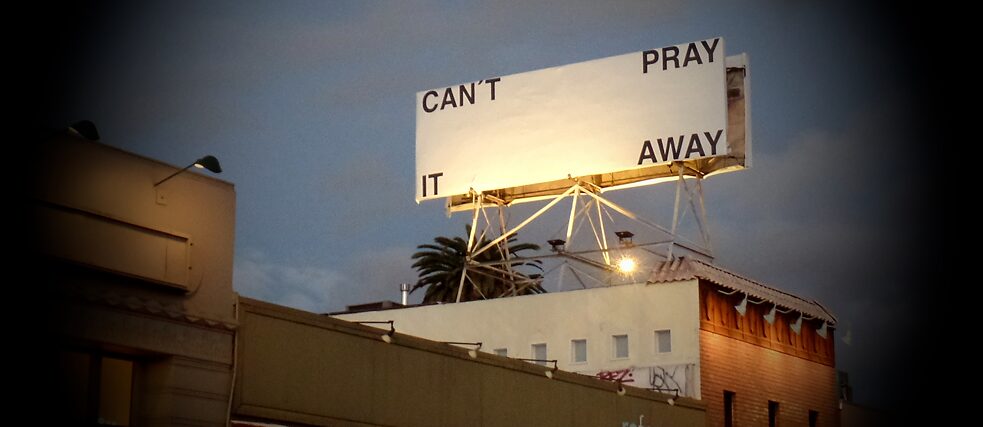

Our attitude is the key, however: no matter how close homelessness has come to us, we cannot stand its proximity. Germans too are “nimbys”: the homeless should be somewhere out there, but “not in my backyard”. Architecture that is defensive and hostile toward the homeless speaks volumes. We should not approach the topic of homelessness only to then lose sight of it again.