Congress and exhibition

Overview of the German library system in 2019

Guaranteeing free access to knowledge and information is the primary goal of public and research libraries in Germany. How is the German library system structured, and what challenges do they face within the sector?

By Jürgen Seefeldt

In Germany, information is considered a significant factor in economic and social progress. Information-sharing establishments, which include libraries, play one of the central roles in this context. Looking objectively at the library system, it soon becomes obvious that – for historical reasons – libraries divide into two main areas: public libraries and research libraries. Their primary goal is the same: helping to spread knowledge in order to create knowledge-based societies, because general, freely accessible information is viewed as a key resource for the economy, politics and democracy.

However, because both types of libraries are different in many ways, it’s a good idea to present each one separately with information on their political and legal backgrounds, to ensure clear understanding of their role as well as their educational and cultural mandate.

Decentralised and networked

The Federal Republic of Germany consists of 16 states. Responsibility for all cultural affairs, science and art, as well as schools and education, essentially falls to the states – as defined in basic law, the German constitution. The towns and communities, of which there are around 11 000, play quite a significant part in this “cultural sovereignty” within the scope of their cultural autonomy at a local level. A national library law, which they do have in many European and Anglo-American countries, doesn’t exist in Germany. It’s true to say that in recent times the parliaments of six of the 16 states have passed extremely general and non-binding library laws that describe the current status of the regional library structures – however they do not stipulate any obligatory standards or provide more detailed guidance regarding provision of a support framework by the funding bodies, nor do they specify entitlement to certain payments.Some of the typical features of the library sector in Germany include its localised structure and absence of a central authority for planning and control – as well as the huge variety of library types and large number of different funding sources, which can be categorised under the headings public, church and private. This diversity opens up plenty of opportunity for independent development and creative journeys – however individualisation also brings with it the risk of fragmentation. But since no library can perform to its full potential if left to its own devices, across-the-board partnerships between the libraries are of immense significance, as is the creation of establishments that provide functions and services from a central point. But most importantly, this situation means that a strong representation of interests is essential at national level. There are four main organisations that make this kind of national control possible, starting with the Deutscher Bibliotheksverband e.V. (DBV, as a union linking the institutions) as well as the two staffing unions BIB (Berufsverband Information Bibliothek e.V.) and VDB (Verein deutscher Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare e.V.), which function under the BID (Bibliothek und Information Deutschland e.V.) umbrella together with the Goethe Institut e.V. and the ekz bibliotheksservice GmbH service for libraries group. The Competence Network for Libraries (knb), which is anchored to the DBV in Berlin in organisational terms and financed by the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK), also fulfils essential coordination functions in several centralised roles.

Public libraries: number, structure, media types

The public library, which fulfils a central mandate in the education system with its provision of services and media, and contributes significantly towards achievement of equal opportunities for individuals, is one of the most widespread types of library nowadays. The database of German library statistics (DBS) lists more than 9 000 public library locations. Their funding bodies are mostly the regional authories in cities and communities, but the Catholic and Protestant churches also maintain libraries in their church communities that are accessible to the general public.In larger cities with more than 100 000 inhabitants, the public libraries frequently amalgamate to form a library system with a central library and branches in the suburbs. These are augmented by special units such as libraries for children and young people, music libraries, an art collection or mobile and school libraries with a branch library function. Admittedly it is still the case that most of the material borrowed consists of printed reference works, fiction and children’s books, but the proportion of media loaned electronically via library websites has been increasing constantly for 10 years and now accounts for 15–20% of all loans. This refers to ebooks, e-papers, digital audio books and e-journals, which are downloaded on mobile user devices such as ebook readers, tablets or mobile phones and made available to users and readers for up to four weeks thanks to the protection of special IT rights management software.

Network publications like this are currently available in over 2000 public libraries (as a 2019) for a growing number of customers. The service is called “Onleihe”, a portmanteau word made up of the term “online” and the German word “ausleihen”, meaning to loan or borrow. The market is defined by two providers, DiViBib, a subsidiary of the Reutlingen-based ekz group, and a company called Ciando. The e-media is only purchased as a licence – so libraries don’t actually have ownership of the media. Many of the participating libraries have joined forces to form “regional associations”, often up to 80 of them, which enables them to use a shared loan platform in combination with cooperatively organised media selection and acquisition to provide a growing e-media pool for the region effectively and at a competitive price. This allows even users living in rural areas to use the “Onleihe” service, as long as they have registered with a participating library.

Mobile libraries, school libraries, libraries for children and young people

In many states, there are communities on the outskirts of town as well as in rural areas in which mobile libraries in the form of book buses are used to supplement static library facilities. There are around 90 mobile libraries operating 110 vehicles, in most cases as part of an overarching library system. Their goal is to bridge the gap between the better-developed library services in towns and less good ones in rural regions. The buses, which offer internet access and WiFi plus an on-board toilet and reading area, provide between 3000 and 5000 media items on their daily tours, with up to six stops each lasting one hour. In rural areas in particular a mobile library serving 15 to 20 stops a week can be a very effective solution.Reading promotion in library terms – in other words making reading fun, teaching reading skills and ensuring information literacy – is something that can be assured by school libraries too. School libraries are places of learning that need to have good amenity value. Admittedly their status in Germany is still inadequate. A variety of organisational structures are used for school libraries. If they are operated as an independent organisation within a school, the school is the body with responsibility and the library services are financed through school funds/donations, or grants from an external sponsor. As well as this model, there are integrated forms, where the school libraries and public libraries use shared spaces and infrastructure, and are often subsidiaries of a municipal library system; this latter version usually tends to be the more effective solution. According to estimates, around 20% of the around 44 000 schools in Germany have an integral school library, or have set up a special reading corner. In objective terms however, only 5 percent of those schools at most have libraries with good resources and well-trained staff. One key factor in the success of school library work is the availability of sufficient space, a regular media budget and above all appropriately qualified personnel with librarian skills as well as educational competence.

Due to the special social, educational and political significance of library work for children and young people, all public libraries devote particular attention to this target group. In many towns a specialist library for children and young people, or a dedicated department, is considered standard. The trend is moving towards separate libraries or areas for children and teens. Special zones for all types of digital media, including consoles for gamers and facilities for relaxing, chatting, working and learning, complement the selection of books. These days, the fittings and furniture in kids’ library areas are designed to be far more colourful, individual and modern than they used to be.

Thanks to the results of last year’s PISA studies, public libraries have been more focused than ever on developing reading promotion as a core activity there. Traditional reading promotion (involving reading aloud from picture books, meet the author sessions etc.) and modern promotion campaigns are part of the standard repertoire today, with the modern approach being more focused on digital and multimedia programmes. Examples are hybrid picture books that work with Augmented Reality. These allow children of pre-school age to experience traditional picture books with text in different ways, using a variety of apps on their tablet or phone, and including sound and video clips.

The proportion of residents with a migration background in cities can be up to 25 percent, which includes 50 different nationalities and language groups. Many public libraries have reacted to the large number of refugees and asylum seekers, and identified them as an important new target group. New ideas for intercultural library work have been developed in order to integrate them as library users. As well as special guided tours of the library and young people’s storytime sessions, it has become common in some places to provide items such as cheap library tickets for refugees or multilingual book packages and media boxes for parents and children. Libraries function as public spaces for social interaction, so that their users can use internet workstations and Wifi networks to maintain contact with their family and friends overseas. Picture books, bilingual and multilingual literature for teenagers and adults, stories and reference books in simple language, dictionaries, English-language books and foreign newspapers have all proved useful to help learn about the German language and society.

What’s new? Makerspaces, Library of Things, libraries as “Third Places”

Libraries are increasingly open to embracing new and experimental ideas, as well as offering the public a forum for practical experiences. Space concepts like Makerspaces help motivate people to join in and experiment. The first humanoid robots, 3D printers and Virtual Reality headsets are being used – all of which are an attempt to familiarise the public with new and important developments, and tap into new user groups for the library.One of these new trends is the “Library of Things”, where – alongside the usual book and non-book media – useful objects such a tools, instruments, kitchen appliances, games, skateboards, sewing machines or child car seats are available for users to borrow – a concept that is becoming increasingly popular.

It’s relatively common to see modern, often architecturally adventurous, library buildings built over the past 12 to 15 years dominating the urban skyline in cities and medium-sized towns. Developing them into a concept termed the “Third Place” has become a matter of library policy in many places: libraries want to be seen in visual terms too, which increases public awareness. If home is seen as the “First Place”, work as the “Second Place”, then the function of the “Third Place” should be to offer a creative way of linking leisure with social interaction, communication and information-sharing. A good premise for making this become reality is that the library here is starting to adopt the role of a non-commercial forum and natural partner by providing attractive, stylishly furnished facilities for interaction and free discussion whilst having access to a broad range of learning and education services, as well as media of all types.

Research libraries: types, sponsors, media

The large group of research libraries includes, at state level, around 100 academic university libraries and more than 200 libraries affiliated to universities of applied science in the 16 Bundesländer, the state and regional libraries with primarily regional (but in some cases national) responsibilities, more than 2500 specialist libraries associated with companies, research establishments, churches, clinics and scientific associations, regional parliament, ministry and high court reference libraries, as well as on a national level the German National Library – which functions as a national depository library and has branches in Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig – the three Central Specialist Libraries (for economics, engineering and natural sciences as well as medicine, the environment and agricultural sciences) and diverse research libraries, plus government, local authority and court libraries at top level. The states or the central government are responsible for funding these establishments, and occasionally mixed funding models are seen. The libraries affiliated to academic universities and universities of applied science are primarily intended to provide literature and information for the benefit of the students there, but they can also be used by non-students for research purposes, although this is not always free of charge. Most universally oriented state / Bundesland libraries serve as regional libraries providing academic information to locations across the region, they also most importantly collect all forms of media works published regionally and make them publicly accessible on the basis of the state-specific depository regulations.Although we can see from library statistics that printed media is still being acquired in large quantities, there is an increase in the proportion of digital media – e-journals, ebooks, retro-catalogued library collections, databases or other electronic resources. Purchasing them or acquiring National and Alliance Licences is usually done by forming a consortium with the support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Federation; DFG), with the result that the financial scope of individual libraries is increased. Tools such as the Database Information System (DBIS), which includes more than 12 000 databases so far, or the Electronic Journals Library (EZB), make access to e-media easier for library users.

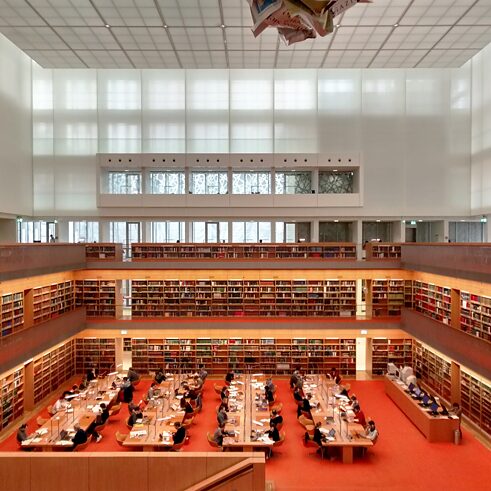

There is a definite tendency towards research libraries becoming intensively used learning spaces. State, regional and university libraries are recording a rise in the number of users who are populating their reading rooms and increasingly using their open access collections. There is often a shortage of working space, so that regulatory measures have to be implemented at short notice, and capacity needs to be increased in the long term. So it’s also essential to continue rolling out construction projects for learning centres or learning environments. Despite increasing digitisation, the library still remains a physical space. In future, construction planning and the need for space will rank amongst the top concerns libraries will face on an ongoing basis in years to come.

Digital libraries, national and international

In the past ten years the focus of the academic library sector has been on the accelerated development of digital libraries, in this context primarily on the creation of centres for digital information and publications. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft funding programmes were oriented towards intensive development of electronic resources. Germany has made a start on the digitisation of its historical collections in line with UNESCO requirements, with the aim of making cultural heritage generally accessible and transforming the country into a nation of digital culture. Many academic libraries have constructed highly productive digitisation centres and offer free online access anywhere in the world to a large number of medieval scripts and other precious ancient artefacts from their collections.It’s true to say that state and regional libraries don’t really have a hope of competing commercially against financial heavyweights like Google Books, so the strength of digitally created library products lies not in their quantity but in their quality and their commitment to guaranteeing free access and long-term availability. What we are seeing is that ease of access to these collections is increasing interest in the cultural treasures and causing more people to be interested in museums, libraries, archives and other cultural establishments.

The idea of the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library; DBB) entails the presentation of Germany’s entire spectrum of cultural and scientific treasures. The target audience for this doesn’t consist solely of academics and researchers, it’s aimed at all members of the public. In terms of perspective, it offers straightforward free access to millions (currently over 24 million items) of books, archive materials, printed music, pictures, sculptures, musical works, and audio/film documents. And yet it isn’t just on a national level that the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek is of particular relevance. As an element of the European Digital Library “Europeana”, which is funded by the European Commission, it also makes an important contribution to raising awareness and improving visibility of the German cultural legacy at a European level.

Implementation of open access and long-term archiving

The German library associations agree with research establishments and numerous academic organisations that open access to scientific knowledge and cultural heritage should be encouraged. The open access movement is promoting a new strategy for scientific communication that’s available alongside existing traditional channels and uses the potential offered by the internet for communicating research results. This form of publishing should allow authors to guarantee rights of freedom and use to all users, and keep a copy of their work on the archive server of a trustworthy institution to ensure that it remains accessible in the long term. Since the alternative publication model competes with the current distribution methods used by traditional publishers, it’s understandable that these publishers view open access publishing as advocated by libraries with a critical eye.There’s no doubt that long-term archiving represents a huge challenge for all the research libraries operating here – another reason being the sheer volume of electronic publications. The German National Library (DNB) law was created as a legal framework for the collection and retention of deposit copies of all “media works in non-phyiscal form” published in Germany, to guarantee general availability. In view of the rapid growth in this sector, libraries, archives and other heritage institutions are on the lookout for practical solutions. This applies in particular to libraries for whom electronic resources represent the main source of information provision. In Germany the DNB is responsible for archiving websites in the “.de” domain, an almost unmanageable task of Herculean proportions. Ultimately the long-term archiving of websites is a matter that’s left to each institution, and the individual state libraries with their regional collection obligations are faced with the necessity of having to manage the situation with budgets that have so far been very limited. In view of the rapid changes in the media and society, preserving the cultural legacy – in both a physical and non-physical capacity – has achieved a high priority status internationally. Germany’s cultural assets are part of a collective human memory, and as such they are of global significance and universal value. Politicians and society have a responsibility to ensure that they are preserved and can be passed down to future generations.

Digitisation of valued collections and global access to them via digital means has some huge benefits – not just from the perspective of users, but also in terms of conservation. But even in a world that’s becoming increasingly digitised, the printed original still has its value and needs to be kept in the long term. To guarantee that, appropriate climate conditions and other protection mechanisms are required to prevent it from being destroyed. In line with suggestions from librarians and with backing from the state, a coordination point was set up for the preservation of written cultural legacies at the Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The aim of this establishment is to gather and analyse information on the preservation of printed cultural assets, develop networks to encourage cooperation between the institutions, draw public attention to the dangers faced by printed cultural assets, and provide support for model projects nationally. For instance, several million printed works and shelves full of paper in archives and libraries need to undergo mass deacidification, because acidifiers and wood-based paper were used for printing them.

Between the present and the future – the library in the digital age

Confidence in the significance and remit of the libraries and their future role in the education and culture framework of an industrial state has not necessarily grown over the past ten years. Will the new technology result in libraries of the future only working within a virtual space, or being replaced by cloud-based libraries? Depending on perspective, the challenges of finding the right strategy to develop a respected culture and education establishment remain immense. Now that we are influenced by the internet, smartphones and digital media, reading printed books is no longer something that’s taken for granted. At the same time we also repeatedly hear of shocking reports that a growing number of people in Germany are functionally illiterate. On that basis, reading skills and reading promotion are still absolutely essential alongside (digital) media competence – throughout life.It’s important to emphasise, not just for the relevant policy-makers but also for the benefit of the media and population, that libraries occupy a key role in an information-based society. Libraries can only do justice to this role and its associated expectations if they recognise and accept the challenges posed by an information-based society, if they consistently take advantage of the scope for technological innovation and organisational improvements, and confront the political, financial and structural weaknesses of the German library system with ideas and creativity – as well as confidence in its function and democratic responsibility on a pan-societal scale.