Solidarność was one of the biggest social movements of the twentieth century: by staging a series of peaceful protests, it fought for and brought about the first elections in an Eastern Bloc state. We look back at the beginnings of the collapse of the Iron Curtain.

Poland in the year 1980: the economy is in tatters. Shelves in shops are empty, and when bread or sugar do happen to be available, people queue for hours to get their hands on the bare necessities. While prices of basic foods soar, wages stagnate. And yet it is not only the economic hardship that bothers people. It is their anger at the feeling of powerlessness, their disappointment at a regime that for decades has rigorously suppressed any attempt to express an opinion or protest. The communist government, firmly in the hands of the Polish United Workers’ Party – which in turn was controlled by the Soviet rulers – found itself facing an existential crisis in 1980.The repressive control exerted by the state apparatus already started to show its first cracks when Pope John Paul II, the still relatively newly elected head of the Catholic church, invited himself to visit his home country in 1979. The deeply religious and Catholic Poles idolized the Pontiff. His sermon ended with an appeal to the Holy Spirit “to renew the face of this land”. This gave new hope to many of his compatriots, leading to a sense of new beginnings in the air.

Enough is enough!

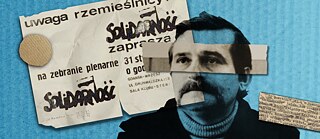

There was particular discontentment in the factories of the coastal region around Gdansk, where large shipyards formed the backbone of industry. Workers laboured under hazardous conditions, were badly paid and had virtually no say in matters. 1970 had already seen a violent uprising in Gdansk when prices were suddenly increased. The government had responded with force – tanks rolled through the streets, shots were fired and more than 80 people died.The final straw came in August 1980, when a shipyard worker was fired just before she reached retirement age,: workers went out on strike and established a union called “Solidarność” (Solidarity) led by Lech Wałęsa, an electrician who had also been involved in the 1970 protests.

The strikers reached an agreement with the government after 18 days: the first independent trade union in a communist country was permitted. This was a historic turning point, as Solidarność was by then a mass movement. It had nearly ten million members by the end of 1981 – roughly a third of the Polish population.

A threat to the communist regime

The Solidarność movement was supported not only by the working classes, but also by intellectuals and the Church. It embodied the hope of a democratic future for a country that had been oppressed for decades. The organization demanded fundamental reforms and came to pose a growing threat to the Polish government and the entire communist system in Eastern Europe.This prompted the regime to take tough action: on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland, which led to massive suppression of the opposition. Solidarność was outlawed, its leaders – including Wałęsa – were arrested and the movement had to go underground. The spirit of resistance remained unbroken, however. Solidarność survived in exile, supported by international solidarity movements, especially in Western Europe and the USA. And it survived above all thanks to the support of the Catholic Church and its Polish head. Pope John Paul II not only travelled to his home country several times during this period of upheaval, but also attracted considerable public attention in 1983 by visiting Wałęsa, who was under house arrest at the time. Besides providing Solidarność with financial support from the Vatican Bank’s funds, he sought dialogue with the Polish military, which resulted in martial law being lifted.

A political thaw and free elections

Trust in the Polish government continued to erode. Solidarność became a symbol of resistance to the system and inspired opposition movements in other Eastern Bloc states.The leaders in Moscow also realized that it was no longer possible to simply continue their repressive stance: in the Soviet Union, CPSU General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev had begun his reforms of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), expanding the scope for political change in Eastern Europe. Economic and social pressure in Poland ultimately resulted in negotiations between the government and the opposition, leading in 1989 to the famous Round Table talks.

These negotiations paved the way for – to some extent – free elections in June 1989. Solidarność won all the seats they were able to stand for and the communist regime was forced to form a coalition government with the opposition. In August 1989, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a close confidant of Wałęsa, became the first non-communist prime minister of an Eastern Bloc state since the Second World War.