The Goethe-Institut

Around the World

The Goethe-Institut has more than 150 locations worldwide; some housed in historical buildings, others in temporary pop-up spaces. They bear witness to a rich and varied history and have weathered political upheavals, crises and natural catastrophes over the decades.

Starting in Germany

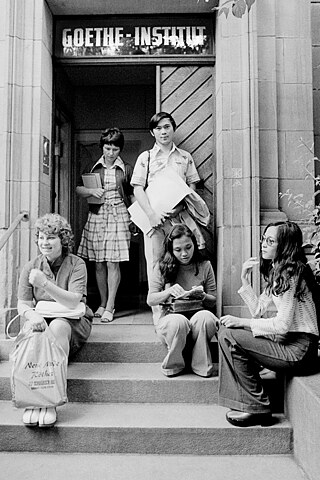

The challenge: show Germany in the best possible light. The question: how to come across to visitors as open, hospitable and peaceful and highlight the positives of a country that was waging war against half the world just a few years before. The answer: focus on idylls with small-town charm, country air and half-timbered houses. So the Goethe-Institut establishes the first institutes in small, southern German towns in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Like the Alpine town of Bad Reichenhall, the villages of Murnau and Kochel near Oberammergau, and the small village of Achenmühle near Rosenheim. This has an added benefit: the cost of accommodations for language learners are lower too. And what could create a better environment for young foreign students to learn German than places with few distractions apart from alpine meadows and mountain streams? The number of institutes in Germany grows to twelve by the end of the 1950s. Ultimately, around twenty schools are established in the Federal Republic of Germany in the first two decades after the organisation is founded.

The first institutes

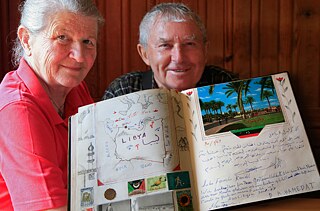

A guest book serves as a record of cultural exchange and hospitality

In Höhenmoos not far from Achenmühle, young people from Alaska, Spain and Singapore meet for lunch or musical events at the Kreidls’ inn in the 1960s. They host individual Goethe-Institut language students for a few months at a time, and many personal relationships develop. Visitors leave a written record of their stay in a guest book. “I’m leaving, but my heart will always be here,” one Spanish student writes in farewell. Even decades later, some Goethe-Institut alumni make it a point to drop in on the Kreidls whenever they are in Germany. A lot has changed since then. The Goethe-Institut Achenmühle no longer exists, and in 2021 Maria Kreidl passed away at the age of 87. Still the memories remain, forever held fast in a guestbook that tells stories of convivial evenings, cultural exchange and hospitality.

Learning German in Schwäbisch Hall also means seeing the big picture in a small setting.”

Text BoxIn the 1970s and 1980s, the Goethe-Institut adapts its location concept to changing demand and greater competition from other language course providers such as universities and adult education centres. The newer schools are preferentially located in larger cities or university towns like Göttingen and Freiburg. Today, the institute in Schwäbisch Hall, founded in 1965, is the last one not located in a major German city. Institute director Sabine Haupt does not see this as a disadvantage: “I think our small town is the ideal German city,” she says, adding: “Learning German in Schwäbisch Hall also means seeing the big picture in a small setting.”

The times are changing

Just one year after the Goethe-Institut is founded, the first international institute opens in Athens, and activities beyond Germany’s borders rapidly take off in the 1960s. The Federal Republic of Germany has opened itself to the world again and is being represented by the Goethe-Institut as a German cultural institution. Spearheaded by then head of the Cultural Department at the German Foreign Office Dieter Sattler, around 100 German cultural institutes maintained by the Foreign Office and German-foreign societies abroad are gradually integrated into the Goethe-Institut from 1959 onwards. Over the years, a comprehensive network develops and institutes in places like Athens, Brussels, Rome, Madrid and Paris are joined by counterparts in Bangkok and Buenos Aires, Tokyo and Tel Aviv, Chicago and Córdoba.

Meanwhile, the world is in a state of upheaval: Many colonies in Africa and Asia gain their independence after World War II, so a number of new nation states emerge in the mid-20th century. The Goethe-Institut responds by establishing institutes in these countries, including in Tunisia, Morocco, Ghana and Togo. The Goethe-Institut network grows rapidly during this time, increasing from 31 to 81 institutes from 1960 to 1962.

Little is quiet in the East

The 1990s also see a wave of new institutes as the world hits a political turning point when the Iron Curtain falls. This historic moment ends the Cold War and changes a bipolar political constellation into a multipolar one while opening up a whole new world of culture. Supported by the German government, the Goethe-Institut reacts immediately and expands its network towards Eastern Europe – starting with the Goethe-Institut in Budapest (Hungary) in 1988. Goethe institutes gradually pop up in other former Soviet Union states, like Russia, Bulgaria, Latvia and Kazakhstan.

The staff involved in founding institutes in the newly emerging states enjoy a special experience full of challenges and moments that are probably unique to a time of upheaval. The institute’s buildings still tell part of this story today – like the stone building in Prague, which stands tall directly on the banks of the Vltava River. “It’s a magnificent building, but it was still full of the furniture and atmosphere of the former GDR embassy,” long-time programme director Monika Loderová says about moving into the prominent building on the riverbank.

German Communist ambassadors and GDR politicians once ruled here. Windows were broken and swastikas smeared on the walls during the Prague Spring in 1968. In autumn of 1989, clerks issued travel passes for GDR citizens wanting to leave the country from the offices of the historic building. In the immediate post-reunification years, the building was finally transformed from a house of politics into a house of culture, of language, and of understanding when the Goethe-Institut moves in in 1990. Goethe-Institut staff were enchanted by the magic of this contrast – and the magic of a new beginning when hope and euphoria were in the air, along with “the feeling that anything is possible now,” Loderová says.

The Goethe-Institut Prague opens

“We were basically squatters.”

He was looking around for a suitable building for the new Czech Goethe-Institut in Prague when his wife asked, “Why don’t we move into the GDR embassy?” “The GDR had already paid the rent until December 31, but basically made no claims on it.” The institute’s founding director Jochen Bloss did not hesitate and he and his wife moved onto the fourth floor of the old building, into a former radio operator’s flat. He set up the Goethe-Institut’s rooms one floor below. “We were basically squatters,” Jochen Bloss says. Moving in was like travelling to the GDR with all the plastic furniture and crockery so typical of the country and all the pencils freshly sharpened, as if the previous tenants had just stepped out for a bit. This was the setting for their new beginning.

Quotes taken from “Das Goethe-Institut. Eine Geschichte von 1951 bis heute” (The Goethe-Institut. A history from 1951 to today.) by Carola Lentz and Marie-Christin Gabriel, scheduled for publication in November 2021 by the Klett-Cotta Verlag.

Taking part in the world, doing cultural and language work around the globe, always involves the risk of getting caught up in the maelstrom of political upheavals and crises. This experience was not limited to the institutes in the Eastern European countries founded during the post-Cold War transition period. Other sites have survived bombings, like the institutes in Paris and Madrid in the 1970s targeted by left-wing extremist terror, or natural disasters, like the 2010 earthquake in Chile that severely damaged the institute’s building. Some institutes have had to suspend their activities when civil wars broke out, such as in Damascus (Syria) in 2012, or in Kabul (Afghanistan) in 2018, when the German Embassy was attacked. Others, however, were able to remain open despite sometimes war-like conditions, like the Goethe-Institut Beirut during the Lebanon conflict.

A tale of everyday heroics

“The story of every person I meet in Lebanon is the story of this war,” author Michael Kleeberg writes in his Lebanese travel diary “The Beast That Cries.” The small country situated between Syria and Israel experiences some terrible years, civil war years from 1975 onwards. Almost all foreign cultural institutes close their Lebanese branches one after another, and the Goethe-Institut headquarters also withdraws its German staff from the region for security reasons.

But the Goethe-Institut Beirut keeps its doors open – thanks to Simon Yussuf Assaf. The Lebanese theologian has just returned from completing his doctorate and teaching in Strasbourg and Freiburg and assumes responsibility for the Goethe-Institut on Park Street’s cultural programme when the war breaks out. Undaunted in the face of serious peril, he keeps the office open and continues to hold events and engage in cultural exchange. After meeting Assaf during a visit to Beirut in 2003, Kleeberg describes him as “a model of civil courage and decency”. Kleeberg reports that Assaf is taken across the front line known as the “Greenline” in an armoured car every day, even during the hot phases of the war, to the western and Muslim side of the city where the institute is still located today.

Here Assaf also sees a film crew setting up equipment in 1980, five years into the civil war: Volker Schlöndorff, who has just won an Oscar for his film “The Tin Drum,” is daring to film Nicolas Born’s novel “The Forgery” (1979), set in Beirut at the time of the war. Later Schlöndorff recalls how frightened the film team is when it gets to the country and sees all the weapons, refugee camps on the side of the road, barricades on the highway and “huge mounds of earth between decapitated palm trees.” But rooms in the Goethe-Institut give him a sheltered space to work in for a few days as he films a scene with Bruno Ganz and Hannah Schygulla scripted to take place in the German embassy.

But even the most enduring and resilient place is not invulnerable: The devastating explosion in the port of Beirut in the summer of 2020 causes extensive damage to the Goethe-Institut building, and one employee is wounded. The colleague has since recovered, the search for new accommodation for the institute is in full swing, the staff has temporarily moved to a nearby co-working space and is still organising events and language courses from there – as unflinching in the face of danger as Simon Yussuf Assaf once was.

In the past, many other institutes have also been fortunate to have loyal staff who show great courage and determination in the face of adversity. Not just with political crises either: some deal with natural disasters and difficult infrastructural conditions. In 2020, for example, when super cyclone Amphan rages through India and Bangladesh with wind speeds of up to 185 km/h, security guard Narayan Muhuri protects the Goethe-Institut Kolkata from major damage. In 2020, he is awarded the Klaus von Bismarck Prize for his efforts.

Pop up – a Goethe-Institut you can touch

Like in the Goethe-Institut Prague, many of the cultural and language institute buildings are steeped in a rich history. The Goethe-Institut Riga is an example of how skilfully this history can be combined with modernity. Founded in 1993, on March 15, 2021, the Latvian branch of the cultural institute moved into the elegant Bergs Bazaar (Berga Bazārs) shopping arcade, a historic pedestrian mall built between 1887 and 1900 that is now one of Riga’s most popular shopping destinations. And while the surroundings pay homage to days gone by, the institute’s premises are very contemporary with work spaces designed for flexibility. Here ideas and projects unfold in creative offices, and employees and students can work and study on the move.

It is our little Goethe-Institut you can touch.

The concept currently being promoted in the USA and some other countries is also forward-looking and flexible. The challenge in such a large country is how to ensure a high level of visibility despite the vast distances. One solution is to concentrate exclusively on the classic metropolises like New York, Washington and San Francisco. The Goethe-Institut is trying a more innovative approach, testing pop-up institutes in places like Kansas City, Atlanta and Seattle. Similar to pop-up stores, these are temporary branches housed in empty storefronts where Goethe-Institut staff can develop a diverse program, establish a cultural network with Germany – and have an impact on the society of their country and city.

The fact that the pop-ups are temporary project spaces does not detract from their success, the director of Goethe Pop Up Seattle Arabelle Liepold says. Quite the opposite in fact: “Our programme range is consistently well received, and our visitor numbers continue to rise.”

In her view, the pop-up concept has many advantages. It will allow a comprehensive network beyond the fixed institutes and cities to develop in the coming years and decades. And for the public, the concept is an exciting addition to Seattle’s cultural life: “The open spatial concept of the pop up and the fusion of exhibition space and workplace dissolves the traditional barrier between visitors and staff.” Even visitors who have no previous connection to Germany are interested in dropping in to learn more about the Goethe-Institut’s work. “None of the other countries’ cultural institutes in Seattle offer a comparable concept that allows for such immediate connections,” Liepold asserts. Over the course of its nearly three-year existence, she says, Pop Up Seattle has become the city’s main point of contact for German culture and German-American relations: “It is our little Goethe-Institut you can touch.”

Modelling sustainability

Unlike the Goethe Pop Up Seattle, the Goethe-Institut in Mexico City is long established. Founded in 1966, it is located right in the centre of the constantly expanding megacity. From the outside, visitors can immediately see that this is a locus of creative work where the important questions of the future are being addressed: The Goethe-Institut in Mexico City is surrounded by a green wall comprising moss and ferns instead of concrete that emits a welcome breath of fresh air for passers-by in the stuffy city.

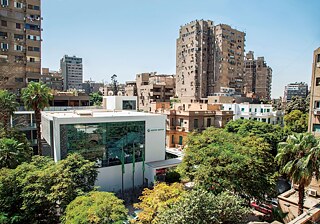

Many of the institute locations have buildings designed to showcase the Goethe-Institut’s dedication to sustainability and climate protection. It is hard to image a more urgent issue right now than making sure this world is still liveable in the decades to come. Many locations, such as Alexandria (Egypt), Bucharest (Romania), Bogotá (Colombia) and Mumbai (India), operate their own small garden plots as part of the “Goethe-Garten” project. Ginkgo trees grow here, strawberries are harvested, attractive spaces are created for bees and other insects, and knowledge about gardening is shared in lectures and workshops. Exhibitions and art projects also take place in the gardens.

Other institutes taking a far-sighted approach include the Bangkok (Thailand) branch, which – in a country whose beaches are threatened by kilometre-long carpets of plastic waste – has committed to the no-plastic maxim, and the Goethe-Institut in Amman (Jordan), which almost exclusively generates all its own electricity via solar power. In this very sunny city, the mobile solar energy plant on the roof can cover 95 percent of the institute’s electricity needs, which also saves money. The Accra (Ghana), Seoul (Korea), Bangalore and Chennai (India) sites also produce their own solar power, while Helsinki (Finland) exclusively uses wind power to meet its in-house energy needs.

In numerous language, cultural, educational and information projects around the world, the Goethe-Institut is addressing climate and environmental issues, and holding events to discuss the development of sustainable cities and climate-friendly architecture. Now, together with its employees worldwide, the Goethe-Institut has developed an action plan with steps for boosting sustainability. “We are expanding on our previous efforts to raise institutional sustainability,” sustainability officer at the Goethe-Institut Daniela Gollob explains. “The goal is to make the Goethe-Institut climate positive and to exemplify sustainability – based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – across the board both internally and externally.”

Working with the UN for a better climate

Upcycled baubles and a Christmas tree

In 2018, the Goethe-Institut Bangkok not only banned disposable packaging from its offices (or came up with creative uses for packaging that was unavoidable, like ornaments for a Christmas tree), and began teaching sustainability and environmental protection in German lessons at schools. As soon as the institute in Thailand can reopen after a Corona-related closure, it also plans to take the lead in developing a comprehensive sustainability management strategy together with the United Nations Environment Programme. The aim is to implement further environmental and climate protection measures for all institutes in the Southeast Asia, Australia and New Zealand region.

The sustainable approach will soon be particularly impressive in Dakar, Senegal, where the Goethe-Institut building will be constructed from materials used in Africa’s traditional architecture: clay, plant fibres, wood, stones, straw. For centuries, buildings on the African continent have been constructed from natural materials with only one problem: They often cannot withstand rain or wind. Sheet metal and cement have therefore gained more prominence in recent years, but they are not climate friendly. “Clay is absolutely a durable building material; you just have to know how to use it properly,” Francis Kéré says. In his birth country Burkina Faso, he has already shown how pressed clay panels, known as BTC (Brique de Terre Comprimée), can be used to construct ecological buildings. Now he will implement this philosophy in the new Goethe-Institut building in Dakar.

He and the Goethe-Institut share the same values when it comes to climate protection and sustainability, the award-winning architect says. The institute’s building will not only be constructed from locally available building materials; it will also be outfitted with contemporary, high-quality technology and offer space for around 600 students. Sustainability officer Daniela Gollob is fully on board with the architect’s plan: “It will be a modern building, but one inspired by local construction traditions and that is highly energy efficient – that’s what I call a forward-looking concept.” The future is already beginning in Dakar.