Phasing out coal

The energy revolution

Working towards sustainable energy for the future: Germany wants to completely abandon coal mining by 2038, an ambitious goal with quite a few obstacles still blocking the way.

By Petra Schönhöfer

For centuries, mining and coal extraction have been as integral to Germany as the automobile industry is today. The Federal Republic of Germany is the biggest producer of lignite or brown coal in the world with a mining tradition dating back to the 17th century. For a long time, brown coal was considered a reliable source of electricity since it was cheap to mine and the reserves seemed practically inexhaustible. Today we know that brown coal reserves are by no means infinite and that getting them out of the ground causes massive environmental damage, destroying the landscape and emitting huge amounts of CO2.

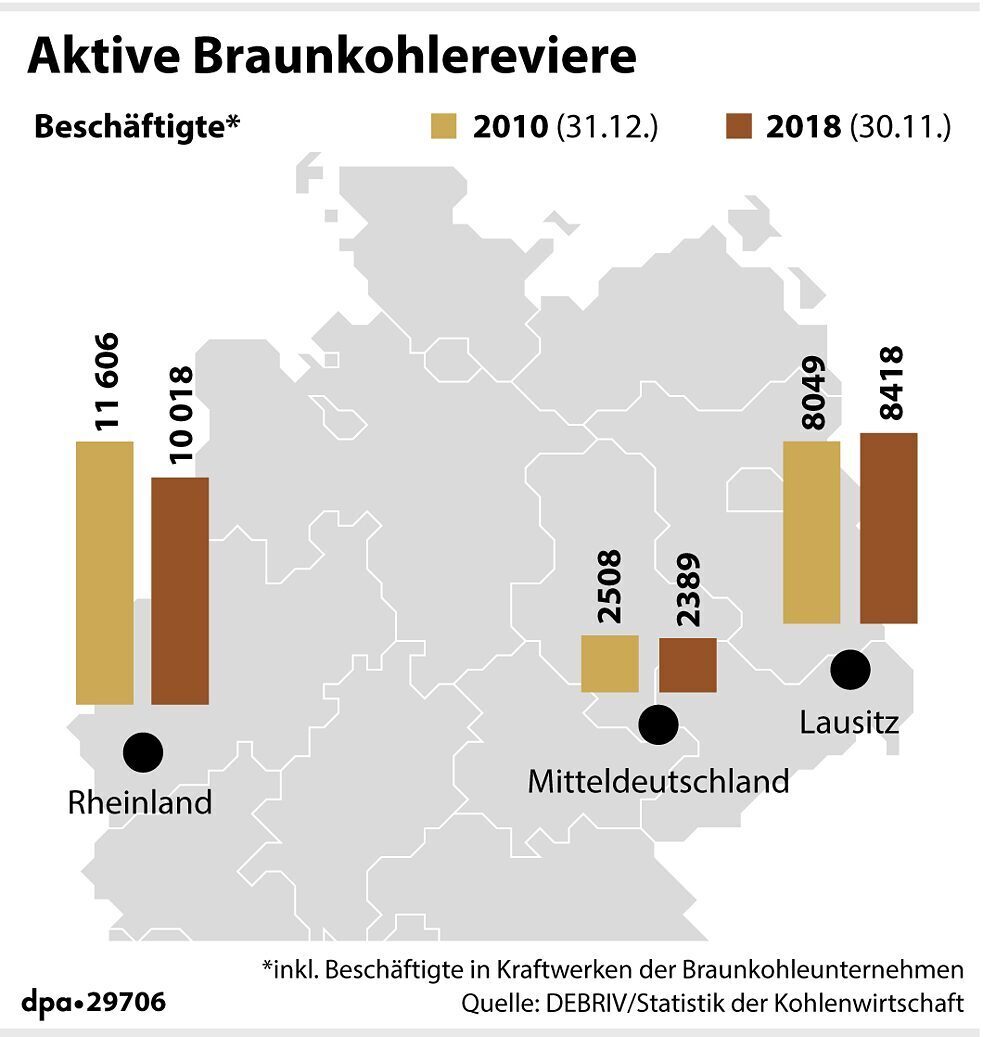

There are still three regions in Germany that actively produce brown coal. Number of people employed in coal mining, including those working in the coal industry’s power plants, in the Rhenish (Rheinland), the Lusatian (Lausitz) and the Central German (Mitteldeutschland) districts.

| Photo: © dpa-infografik

At the latest since the Fukushima disaster put nuclear energy on the list of energy sources in dire need of replacement, the pressing need for an energy revolution has been clear. Germany signalled its willingness to shift its energy production by signing on to meet the goals set at the 2015 World Climate Conference in Paris. The “2050 Climate Protection Plan” adopted by the Federal Government in 2016, which includes reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent compared to 1990 levels, focuses on a complete phase out of coal. The targets have been set - but the path to meeting them still has to be blazed.

There are still three regions in Germany that actively produce brown coal. Number of people employed in coal mining, including those working in the coal industry’s power plants, in the Rhenish (Rheinland), the Lusatian (Lausitz) and the Central German (Mitteldeutschland) districts.

| Photo: © dpa-infografik

At the latest since the Fukushima disaster put nuclear energy on the list of energy sources in dire need of replacement, the pressing need for an energy revolution has been clear. Germany signalled its willingness to shift its energy production by signing on to meet the goals set at the 2015 World Climate Conference in Paris. The “2050 Climate Protection Plan” adopted by the Federal Government in 2016, which includes reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent compared to 1990 levels, focuses on a complete phase out of coal. The targets have been set - but the path to meeting them still has to be blazed.

Phasing out coal by 2038

Politically, important steps have already been taken in the right direction. In 2018, the German government founded the Commission for Growth, Structural Change and Employment, known as the “Coal Commission” for short, to support progress towards its energy sector goals. Stakeholders from politics, the private sector, environmental organisations, unions and the states and regions affected worked together to draft a plan for phasing out coal and the accompanying structural changes this will require in Germany. The plan puts Germany on a course to be completely independent of coal-fired power plants by 2038 at the latest. 12.5 gigawatts from lignite and hard coal-fired power plants - around 28 percent of today’s coal-fired electricity production - are to be shut down by 2022, which would halve annual CO2 emissions in the electricity sector by 2030.

In September 2019, the Federal Government launched a comprehensive package of measures to implement the Commission’s goals. The ambitious bill underscores the federal government’s determination to achieve greenhouse neutrality by 2050. It is set to make rail travel cheaper, air travel more expensive, and to completely do away with oil furnaces in private homes. The largest single item in the 2030 climate protection programme though is the phasing out of coal-fired power generation - and the second largest is the expansion of renewable energies to 65 percent by 2030.

Tens of thousands of people from all over Germany took part in protest marches to save the Hambach Forest.

| Photo: © picture alliance/chromorange

Tens of thousands of people from all over Germany took part in protest marches to save the Hambach Forest.

| Photo: © picture alliance/chromorange

Weighing the importance of trees versus jobs

Despite the clear goals set, the energy revolution will not be easy. Phasing out coal is a social powder keg, and while opponents of brown coal push for quick action, resistance is strong in other segments of society. These tensions came to a head in Hambach Forest in 2018. The wooded area bordering the Etzweiler lignite mine in North Rhine-Westphalia was slated for open-cast mining. For weeks, hundreds of environmentalists and activists occupied the woods threatened by imminent deforestation, and tens of thousands of demonstrators from all over Germany came to show their support. At the same time, unions and workers from the brown coal industry are fighting to keep their jobs. The energy revolution is experiencing backlash in other regions, too, places where new wind farms are to be built, for example. Residents argue that the huge rotors cause noise pollution and threaten the environment and cultural assets, and have filed injunctions to try and stop wind farms springing up in their backyards. The approval process is basically at a standstill, blocking the urgently needed expansion of wind energy.

Hard coal phase-out as a model

In the heated debate, it is easy to lose sight of the significant progress that has already been made. In 2019, coal has already lost its dominance in the mix of energy sources used in Germany. A study by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, ISE, found that photovoltaics and wind were the largest sources of electricity in Germany, jointly producing more electricity than coal in the first half of 2019. Combined with water and biomass, renewable energy sources accounted for almost half of public net electricity generation. And hard coal has already been phased out as part of the ongoing energy transition. The last German colliery closed in Bottrop in December 2018, taking the largest hard coal mining areas off the grid. In its heyday, it employed more than half a million people and produced over 110 million tons of hard coal per year. Then coal lost its international competitive edge and recently more than one billion euros in coal subsidies per year were spent making up the price difference on the world market. So in 2007, the Bundestag decided on a timetable for phasing out the coal being mined at a loss. The RAG Foundation was formed the same year to handle regulated withdrawal from production and the lasting impact on the environment. The hard coal phase-out is regarded as a model because it was socially responsible, took environmental damage into account, and provided economic security.