A musical Oral History Performance

Colonialism

“The intention was to look at people who we don’t usually associate with the fight for independence in their own countries. In Kenya, yes, we look at Dedan Kimathi, but do we look at his wife, Mukami? The story of colonialism is a personal story. It isn’t just a curriculum. There are stories behind those numbers.”

By Abigail Arunga

What would you say if I told you that everything you knew about your existence was simply a fairy tale?

What would you say if I told you that all the things you know to be true—that you are Kenyan, that you belong to a certain tribe; that you can name your ancestors back sixteen generations; that you can point to the land your grandmother grew up on—what if I told you that these are all lies?

What if I took it a step further and said that the English language you are reading now somehow just came to you from a kind of benevolent spirit, and that you never had to suffer or slave to learn it? Would you believe me?

Of course not. No African would believe that their ancestors did not exist. No Kenyan would ever assume that English is the first language of any African nation—unless this African nation was formed last week, and even then, it would be unlikely. The truth is plainly before our eyes: the reason we speak English, the reason we can read this blog, is colonialism.

And yet, all over the world, many history books teach that what we know about our ancestors, about how Kenya was formed, about how Africa was formed, is completely untrue. If mentioned at all, the personal and bloody histories of colonialism are swept under a rug, much like the one you would find at the entry of a house that says “Not Welcome”.

When one reads or hears about colonialism, there is a certain sense of detachment that occurs from what most countries call the ‘global north’ or the ‘developed world’. It’s very easy to say developed world without mentioning the glaring fact that the reason these countries are developed is because they grew strong and mighty on the backs of free and exploitative labour snatched from states that were colonised. It’s a glaring fact in most countries, and it’s a fact that Wangari Grace, also known as Wangari the Storyteller, and Sven Kacirek, refused to further ignore. Wangari Grace is an author from Nairobi with a passion for performance, who has toured with her particular brand of making a stage come alive all over the world. Sven Kacirek was born in Hamburg, Germany, and studied at the conservatory in Arnhem, the Drummers Collective in New York City, and the Musikhochschule in Hamburg. He has been coming to East Africa since 2018 for various projects, and has been acclaimed several times for his work and musicianship.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, Sven got in touch with me on social media. He said, I see you’re a storyteller and musician; I’m from Germany, are you available to meet?” They met in March of 2020, and talked extensively about several things. As they talked, the issue of colonialism came up; in Germany, apparently, the issue is more often than not glossed over, and in Kenya, we learn a very textbook, sanitized version of events—just enough for an exam, but definitely not enough for a revolution. “As we talked, we thought we could produce something for children and adults, telling this often-unexplored story with music, and apply for funding to do it.” Apply for funding they did, through IKF (the International Koproduktion Fund)—which supports artistic projects, through the Goethe-Institut. It sounded like a great plan. Sven and Wangari agreed to keep talking and do more research about their idea for a show as Sven went back to Germany. And then…well, you know what happened then. “The day after he travelled, we went into lockdown.”

Luckily, the fire was already ignited. “We did keep talking,” says Wangari, “all the way to August. We talked about what angle we wanted to take, what stories we wanted to feature. We were very clear that we wanted to tell it from an African perspective.” In August, Sven came back. There was so much work to be done: scripting and deciding what was in or what was out took quite a bit of time— what they had originally planned to be forty-five minutes turned into a three-hour long show. The five countries they narrowed down to were Kenya, Congo, Tanzania, Namibia, and South Africa—countries that had a distribution of colonial powers and all had a story, however gruesome, to tell.

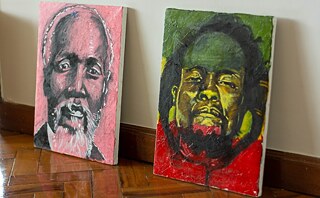

“The intention was to look at people who we don’t usually associate with the fight for independence in their own countries. In Kenya, yes, we look at Dedan Kimathi, but do we look at his wife, Mukami? I mean, she’s still alive! This didn’t happen that long ago!” exclaims Wangari. “There are different angles to the tale, even as a love story. How was her relationship with Dedan affected? What happened to the kids? The family?” Wangari goes on to name Miriam Makeba, another character in the fight for independence, who contributed greatly to her country’s struggle, and was banned for it. Her citizenship was even revoked. “The story of colonialism is a personal story. It isn’t just a curriculum. There are stories behind those numbers.”

I ask Wangari how the show was received, and she says the reception was varied. Some kids who they asked in Buru Buru had no idea where or whom we got out independence from. Another lady at Cheche, part of an older audience, said she had never actually thought about Dedan Kimathi as a human being and a family man. “This happened the other day. He isn’t even an ancestor,” quoted Wangari to me.

One of the things they loved about the performances was that they could be an hour and a half, and then the discussion around it, the questions people had, would be about the same time as well. People wanted details. They recommended places to visit, like the World War II cemetery on Ngong Road. Wangari and Sven would tell them to spread the word because even with this work, even with these thought provoking stories, two people can only reach so many people who don’t know what really happened: that we were colonised, our resources and people were taken and stripped from us, entire legacies and cultures were stolen, and this is a very central pillar of the foreign policy and attitudes that guide how the world works today. Many issues we still have are traced to our pre-independent times, without any acknowledgment or reparation of the past, and what colonial powers had (have!) to do with it. Germany, according to Sven, only talks about losing their colonies after World War II. Meanwhile, streets in Namibia still have German names. “We had people from Italy in the audience who were told that Italians visited Ethiopia and then came back!” Nothing about the real battles fought to make sure Ethiopia was not colonised, like the Battle of Adowa. Nothing about guns, murders, violence. Nothing about real stories. “One school with eight-year-olds came and said that they would like to explore the topic more, because when people are so sheltered, they don’t know most of these things, and it is no longer sensible to bury heads in sand.”

And many heads are still buried. There would be performances in which people would ask them how something that happened so many years ago is relevant now. Wangari would have to explain that even coming to Germany to perform required a visa that she wasn’t sure she could get, because of present-day colonial attitudes that make some passports more powerful than others, and some visas not guaranteed, even after you pay an application fee. “Sven can just apply online, or get a visa on arrival. The story isn’t over. That you can buy premium quality Kenyan tea and coffee at a cheaper rate in Europe than you can from the land in which it is made, speaks to the fact that the story is not over.”

Something else they discuss—that many Kenyans do discuss—is the so-called benefit of colonialism. “In Kenyan schools, we are taught that there were positives to imperialism: ending slavery, bringing manufactured goods, and infrastructure development. But I wonder how a Kenyan today can ask me that. Do we really think that with no Europeans who came to these shores, we would have no education?” I laugh at the irony. Long before there were strangers forcefully bringing anything to Africa, Africa was hailed as the cradle of civilization; known as a centre of wealth and knowledge, in possession of architectural masterpieces such as the pyramids of Egypt and boasting the biggest libraries, markets, trade centres and cities of the world. “Education was happening long before colonisation happened.”

For Sven, research also brought up a few unpleasant snapshots of a time that was not so long ago: a brand of chocolates, very popular in Belgium, that are shaped like hands, rooted in a story of a giant who lived on the banks of a river and would chop off the hands of people who wanted to cross the river but wouldn’t pay him a tax. Which colonial master, do you think, was known for chopping hands off people in their colonies? Belgium, of course!

For now, there is still a lot of interest in the topic. The performance will be put on in Hamburg, the home of the chocolate story, in 2022—which was the original planned location of the first showing, so it is coming full circle. The conversation is still going to go on. “I like the whole idea of this coming up during the pandemic, because when people say: So what? Colonialism happened!, we can show them real life conversations, like the conversation on vaccines and travel bans; the conversations on a strain (of COVID-19) being found in South Africa and then South Africans being banned from travel, even though the strain did not originate from there. And then, when a strain is found in Africa, what are Kenyans doing? Are we also banning Europeans? No, the reverse happens: we send flowers!” She speaks of the instance where the Kenyan government sent healthcare workers in the UK flowers; ironic in many ways, but primarily because healthcare workers in Kenya were not getting flowers, or sufficient protective equipment, and the UK periodically bans Kenyans from travelling to the UK.

“ ‘What are you trying to achieve? You want Europeans to feel guilty? I’m forty. I wasn’t even there!’ We were once told at a show. And that’s why we need to have the conversation about how it looks now, the post-colonialism show. We want people to feel uncomfortable. Uncomfortable enough to change something. Speak about it in circles that this performance may not reach. Speak about immigrants crossing seas and dying en route. Europeans ask why people prefer to die! How did that happen? Let’s ask: what made their countries like that, such that they would rather die than live there? Ask why we have borders. Ask why families are separated by arbitrary lines drawn at a Berlin conference. No one came and asked us. Speak about it and recognise the privileges we all have, because everyone is privileged in a way…even me, who couldn’t do this show without a German partner, because that is how the funding works. It is still post-colonial. Let’s talk about it. Let’s hope that it will change how things run right now.”