Out Film Festival

Shame is a dress I wear long to hide my truth

I’d never thought about shame as a luxury before. I’d never thought about shame much at all. Felt it, yes, but never tried to pin it down and ask it when, why, and how it became part of my life. It wasn’t until the 2018 Out Film Festival (OFF) in Nairobi that I had to scrutinize that abstract feeling when I was confronted with the festival theme, We No Longer Have the Luxury of Shame.

By Gloria Kiconco

Before the festival, I was reading Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs The Patriarchy, a feminist graphic novel by Liv Stromquist . In chapter four, Feeling Eve, or In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens, Stromquist writes, “I once read that the difference between guilt and shame is that we feel guilty for something we’ve done, but we feel shame for what we are.”

This definition brought to mind something that happened to my friends and I earlier in the year.

Two lesbians, two gay men and a gender non-conforming person walked into a club in Kampala. We were stopped by a bouncer at an entrance that led to the outdoor bar. The bouncer wouldn’t let our gender-nonconforming friend through because they were in high-heels, or, in the bouncer’s words, “dressed like a woman.” When we tried to defend our friend, the bouncer pointed to one of our two gay friends and accused him also of dressing like a woman. We decided to leave before the issue escalated. On our way out, the manager, who knew our other gay friend, pulled him aside to say we could use another entrance. We left anyway.

The manager tried to ease his guilt by smuggling us in like sachets of Waragi ; the kind I’d slip in my bra to avoid buying expensive drinks at the bar. This only emphasized that their problem wasn’t something we did but who we are in their eyes and the eyes of Uganda’s law: Illegal goods.

Living in Uganda has left me too familiar with the shame these experiences ignite. It’s like suffering a hundred tiny cuts to the gut but internal bleeding remains hard to detect. It’s a feeling which was articulated in the award-winning short story Jambula Tree by Monica Arac de Nyeko:

“Our names became forever associated with the forbidden. Shame.”

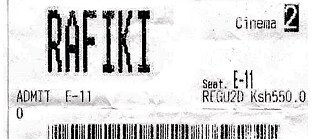

Ten years after Jambula Tree, which is set in Uganda, won the 2007 Caine Prize it was adapted into the film Rafiki by Wanuri Kahiu, a Kenyan filmmaker. Rafiki, which tells the love story of two Kenyan girls – Kena and Ziki – was banned by the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB). They announced on Twitter on April 27th, 2018 that they “banned the film Rafiki due to its homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism in Kenya contrary to the law and dominant values of the Kenyans.” Wanuri Kahiu took the battle to the High Court, arguing that the film couldn’t be submitted to the Oscars Selection Committee Kenya. Months later, the High Court lifted the ban for seven days from September 21 to September 30. By the time of the festival, the ban was back in effect.

OFF 2018 was curated by Jackie Karuti and Muthoni Ngige . They selected nine films - shorts and features, documentaries and fiction - to screen over the four days of the festival. The films came from Chile, Cuba, France, Germany, the UK, the USA, Canada-India, and other countries. Only one, Reluctantly Queer, came from an African country and even then it was a joint Ghana-USA production.

In Reluctantly Queer, an 8-minute short shot in a gritty grayscale, a gay Ghanaian man narrates a letter to his mother over images of his daily life in America: showering, brushing his teeth, holding his lover. He misses his mother but can’t reconcile feeling threatened as a black man in the US and feeling threatened as a gay man in Ghana.

Banning a film is a legal sanction. Shame is the cultural sanction that follows. It’s how culture, community, and country mark the unacceptable, the unwelcome, the taboo. It is an effective tool: one that asks you to do all the work of putting yourself down and keeping yourself in check. It is a form of self-mutilation. This is why we no longer have the luxury of shame. But what does it mean to be without shame? What is the opposite of shame?

The opening night panel was titled Shameless, a word that usually has a negative connotation. It was a candid sharing of stories about queer sexual experiences, primarily lesbian and bisexual experiences because that’s how the panel members identify. Talk about sex and you’ve got your audience hooked. But this discussion was about more than sex. It was about changing the way we feel about letting go of shame. It was about getting the audience to feel that shame is not a birthright or some twisted badge of honour. It was about understanding that being shameless isn’t always a bad thing.

Earlier that day, I was with a few of the panellists that went to visit Ishtar, an MSM health and social well-being centre. We toured the space and met some of the men who do outreach. We also met some of the Ishtar Dolls, a group of artists, designers, and performers. A member of the Ishtar Dolls said something that stuck with me the whole festival. He said it is important to get people to stop seeing them, the Ishtar Dolls and members of Ishtar, only as men who have sex with men. It is important for them to be seen as artists, performers, and all the other layers of their identities instead of reducing them to their sexuality.

Holding the shameless panel on day one felt like an echo of this sentiment. Yes, let’s talk about sex, shamelessly, but let’s also get it out of the way. Because while East African governments are preoccupied with our sex lives and trying to make us feel ashamed about them, we are much more than what we do in the bedroom. (Imagine their disappointment in discovering we mostly use our bedrooms to sleep. Just like everyone else.)

The collective queer movement in East Africa spans decades of hard work. OFF has just finished its eighth edition, making it a relatively young project. Kevin Mwachiro, one of the founders of the festival, told us how in the beginning, the audience was just a handful of people willing to risk attending the screenings. That was in 2010. By 2018, the auditorium was packed and each day it became harder to get a seat for the screening. This is how change often comes about, through perseverance. Through people like Kevin, who start even when it doesn’t seem like the right time.

On the second day of the festival, the panel All the Threatened and Delicious Things Joining One Another brought together such people. Activists, artists, podcast hosts, and bloggers: each working on their own corner of the movement; stitching together a better existence for the queer communities online and offline, in East Africa and as far as South Africa. Each taking their own measure of risk to do so.

Samantha Mugatsia, who plays Kena in Rafiki, was on this panel. She had travelled with the film to festivals around the world. Rafiki picked up at least nine awards along the way. Still, some critics felt the film was conventional for western audiences. But what was conventional for them felt revolutionary when Rafiki finally came home at the end of September and screenings sold out across Kenya. What was revolutionary for Kenya seemed unattainable for Uganda where the film might never be screened. But there was hope. Precedence had been set. In the same way India’s decriminalisation of homosexuality set precedence for the legal battle to repeal similar laws in Kenya.

If it could happen for them, I thought, maybe it could happen for us.

One of the enduring issues on this panel was brought up by Linda Pepper, also known as Kenyan Babydyke to her online community. She believes that leaders, artists, activists, and people with a voice in the queer community hold a responsibility to make room or make progress for the “baby queers” to come. This might mean changing laws, making safe spaces, starting conversations on various levels, creating platforms that were once unimaginable. Neo Musangi; a gender non-conforming scholar, artist, and performer; on the other hand, felt no looming responsibility toward those who might come after them.

As queers, feminists, and artists, it’s easy to place the burden of change on each other or to see our priorities as everyone’s priorities. We place expectations on others and when they don’t live up to those expectations, we lash out.

Sometimes, making headway on behalf of a community is the goal, like when it comes to changing legislation, which is what National Gay & Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC) is doing, or opening up dialogue with bodies of the government that directly impact healthcare funding for MSM, which is part of what Ishtar does.

Den Weg für die nächste Generation zu ebnen ist manchmal eine Selbstverständlichkeit. Neo war sichtbar – physisch, durch Vorführungen über Nicht-Geschlechterkonformitӓt auf den Straßen von Nairobi. Sie waren online über soziale Medien, Blogs und wissenschaftliche Arbeiten sichtbar. Das Schaffen aus eigener Wahrheit, wie Neo es tut, regt andere zum Folgen an, oder ermutigt sie, den eigenen Weg zu finden.

Aus diesem Grund kamen Künstler*innen und Aktivist*innen zur Diskussionsrunde zusammen. Es hat uns daran erinnert, dass es verschiedene Möglichkeiten gibt, Veränderungen vorzunehmen. Die Kunst ist dem Aktivismus an Stärke gleich zu stellen. Die Reflexion erfordert so viel Zeit und Raum wie das Handeln. Das Feiern und der Stolz ergänzen den Widerstand und den Protest.

Freitag, den 9. November 2018 war der dritte Tag des OFF und der Veranstaltungssaal war überfüllt. An diesem Tag moderierte ich die Diskussionsrunde für den Abend, „Pride and Protest “ (Stolz und Protest), bei der ugandische Künstler*innen und Aktivist*innen vorgestellt wurden. Während wir uns auf die Diskussionen vorbereiteten, berichteten die Independent[15-Nachrichten über die Festnahme von zehn Männern auf Sansibar. Es war der aktuellste Bericht in der Flut von Medienberichten über die Verfolgung homosexueller Menschen in Tansania. Die Männer hatten angeblich an einer homosexuellen Hochzeit teilgenommen und sollten deshalb Analuntersuchungen unterzogen werden. Diese überholte und unwissenschaftliche Art der Untersuchung sollte dazu dienen, homosexuelle Aktivitäten unter Beweis zu stellen. Alles, was es jemals sein kann, ist die Verletzung von Menschenrechten.

Während wir uns für das Festival in Nairobi versammelten, stellte der Leiter der Stadtverwaltung von Dar es Salaam, Paul Makonda, ein Einsatzteam zusammen, das homosexuelle Menschen aufsuchen und einsperren sollte. Diese Aktion wurde als ein hartes Vorgehen gegen Prostituierte getarnt. Jedoch verbreitete sich sein Aufruf, Homosexuelle zu melden, auf YouTube und eskalierte zu einer Hexenjagd, die zum online Coming-Out hunderter LGBTQ+ Tansanier*innen führte. Sollten sie erwischt werden, müssten sie wegen „Geschlechtsverkehrs mit einer Person, der gegen die natürliche Ordnung spricht“ mit 30 Jahren Gefängnis rechnen.

Die Lage in Tansania war ein eiskaltes Echo von Uganda 2014, als tausende LBGTQ+ Ugander*innen angesichts des infamen Gesetzes gegen Homosexualität aus dem Land flohen, um den Auswirkungen zu entgehen. Das hat starke Angst and Scham in uns wiederbelebt, die durch öffentliche Demütigung ausgelöst wird.

Das Pride and Protest Panel stellte durch Geschichten über Trauma, Ausdauer und Frustration eine emotionale Reise dar. Er war zudem ein Ort der Heilung, da wir Gedichte und Geschichten der Solidarität austauschten und sogar einen stärkenden Zauber durch unsere örtliche Hexe, Verteidigerin und Aktivistin Mildred Apenyo teilten. Die anderen Mitglieder des Panels waren Godiva Akullo, eine Rechtsanwältin, Aktivistin sowie Schriftstellerin, und DJ Racheal, eine Musikproduzentin und Aktivistin. Alle waren auf die eine oder andere Weise Spitzenreiter*innen gewesen. Sie kannten nur zu gut die Panik, über ein bekanntes Foto in einer Boulevardzeitung zu stolpern, den Terror einer Polizeirazzia – die Erinnerung ließ immer noch ein Zittern durch Godiva‘s Hӓnde laufen – und die anhaltende Qual, als ein Verbrechen auf Beinen angesehen zu werden. Soweit wir uns den Schmerzen stellten, tauschten wir Strategien darüber aus, sie zu überleben, zu heilen und zu gedeihen.

Als die Diskussion zu Ende ging, lud Mildred Godiva ein, eine Nachahmung von Mato Oput, eine Acholi-Zeremonie der Vergebung und Versöhnung, vorzuführen. Jeder legte seine Hand auf den Kopf des anderen und sprach Wörter der Vergebung, die den stillen Veranstaltungssaal füllten. Mit diesem Versöhnungsakt zielte Mildred darauf ab, das anwesende Publikum an etwas Einfaches, etwas Monumentales zu erinnern. Wir müssen einander vergeben. Wir müssen uns vergeben. Wir müssen uns versöhnen.

Wie viele andere Bewegungen, ist die Schwulenbewegung in Uganda (und in Kenia) von internen Streitigkeiten, Gerangel um Finanzierung und lang-gehegtem Groll geplagt. Solche Probleme bringen uns oft noch weiter zurück als die öffentliche Diskriminierung oder das Verbieten von Filmen. Sie segmentieren eine bereits segmentierte Vereinigung von Individuen, bis wir isoliert dastehen.

Am Samstagabend sprach Jim Chuchu beim Abschlusspanel „The State, the Award and the Academy“ (Der Staat, der Preis und die Akademie) darüber, wie sein erster Spielfilm, Stories of Our Lives (2014), in Kenia verboten wurde. Stories of Our Lives, eine Anthologie von fünf Geschichten aus Kenias LGBT-Gemeinschaft, wurde mit einem Teddy Jury Award ausgezeichnet. Der Teddy Award ist eine Auszeichnung für Queere Filme, die von Wieland Speck, einem deutschen Filmregisseur, mitbegründet wurde. Dieser wurde vom Goethe-Institut als Ehrengast eingeladen und saß neben Jim Chuchu. Andere Teilnehmenden an der Diskussion waren die britische Drehbuchautorin und Regisseurin Dionne Edwards, sowie Aida Holly-Nambi, die bei None on Record und zugleich als Reporterin und Produzentin des Podcasts AfroQueer arbeitet.

Nach dem Abschluss der Diskussionen hielt die Kuratorin Jackie Karuti eine kurze Rede. Darin erwähnte sie, wie jemand ihr vorgeworfen hatte, nicht queer genug zu sein, um das Out-Filmfestival zu kuratieren.

- - - -

Lasst uns hier eine Pause für ein Pop-Quiz einlegen.

1. Dieser Angriff zielte darauf ab

a. was sie ist oder

b. was sie getan hatte

2. Dieser Kommentar sollte in ihr

a. Schamgefühle oder

b. Schuldgefühle erwecken

Als ich gebeten wurde, diesen Artikel zu schreiben, wurde ich ängstlich, weil mich eine anhaltende Stimme im Hinterkopf fragte: Was macht dich würdig, dies zu tun? Welche Autorität hast du, dies zu schreiben? Was weißt du überhaupt darüber?

Es ist natürlich, zu befürchten, was andere zu uns oder über uns sagen werden. Es ist natürlich, zu befürchten, dass sie uns in Fetzen reißen werden, wenn auch nur, um sich selbst aufzubauen. Anstatt Kritik zu üben mit der Absicht, unsere Fehler zu korrigieren (und wir alle machen Fehler), führen unsere Feinde wie auch Verbündeten unsere Fehler auf unsere persönlichen Schwächen zurück. Das ist ein lähmendes Gefühl. Eine Illusion, der man sich leicht hingeben kann. Sie hält uns davon ab zu realisieren, dass wir es Wert sind zu schreiben, Festivals zu kuratieren, Filme zu machen, Kunst zu schaffen, Podcasts aufzunehmen und zu feiern, sowie zu überleben und zu gedeihen.

In ihrem Essay, „Poetry is Not a Luxury” (Die Poesie ist kein Luxus), schreibt Audre Lorde:

“For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams towards survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.”

(Für Frauen ist die Poesie daher kein Luxus. Sie ist eine elementare Notwendigkeit unserer Existenz. Sie macht die Qualität des Lichts aus, innerhalb dessen wir unsere Hoffnungen und Träume vom Überleben und der Veränderung verankern, die erst in Sprache, dann in Ideen und schließlich in konkretere Maβnahmen umgesetzt werden.)

Diese Worte sind der Grund dafür, dass ich schreibe, auch wenn ich an mir selbst zweifle. Weil es für meine Existenz wesentlich ist.