Future Perfect

Stories from around the world and Pakistan for sustainable future!

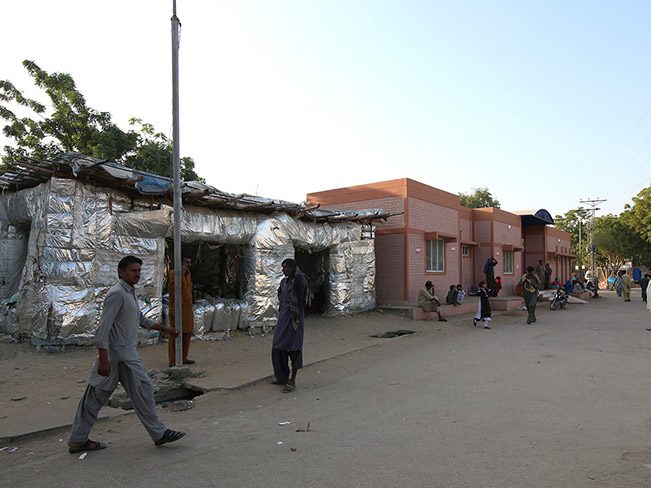

Photo: Basil Andrews

One woman’s struggle to recycle Karachi’s waste leads to the creation of an alternative technology in housing. Wherever temporal shelter is needed, this silver structure is a viable option.

I step out of the “Chingchi” – the local three-wheeled mode of commuting – and pay the driver. I walk through the side entrance of the Mithi Civil Hospital and onto an unpaved path. On my right is the outpatient department. To my left is a silver-colored box-shaped building: a visual oddity, a stark contrast to the wards section ahead, made of cement and concrete.

This oddity is called the Chandi Ghar (Silver Home), and it is one of many products developed by Gul Bahao, an environmental NGO that was set up by Nargis Lateef – a botanist by education, an environmentalist by thought and action.

Gul Bahao – which means ‘to spread fragrance’ in Urdu – is the 22-year-old result of Nargis’ mission to solve Karachi’s complex waste management and disposal issues, at the same time as presenting a new approach to housing and shelter. Together Nargis and her team of skilled migrant workers indigenously developed cheap solutions towards these problems – meaning that they developed these solutions without modern technological tools, and locally. Some of them are: instant compost, mobile toilets and water purification methods. Today, the Chandi Ghar building is the star product developed by Gul Bahao. Borne from necessity and experimentation The Chandi Ghar technology has evolved through a series of experimentation and research. As Nargis narrates, “One day I was sitting at our research camp, resting. It was the middle of the afternoon and this boy comes to me and shouts excitedly, ‘Baaji! baaji! Mein ne diwaar banaadia! dewaar banaadia!’ (Sister! Sister! I’ve made a wall! I’ve made a wall!). I go out and I see these blocks lying on the ground.” Now called “wastic” blocks – merging “waste” and “plastic” –, the Chandi Ghar building materials arose from what Nargis repeatedly says: “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Today, the “wastic” blocks are made from BOPP (Bi-axially Oriented Polypropylene) films, i.e. from the excess or rejected materials of packaging companies in the city. These films were chosen when the team observed that they kept Chandi Ghar users cooler than the discarded plastic shopping bags that were initially used in the “wastic” blocks.

Nargis’ vision of recycling waste into shelters has more manifestations: After the 2005 earthquake in northern Pakistan, Nargis found the chance to test a prototype of the Chandi Ghar at a site in Mansehra. Makeshift homes were built for displaced families until they rebuilt their own homes. A year later, the second model was deployed at the Mithi Civil Hospital and was funded by individual donors and a school.

At Mithi – the capital of Tharparkar district in Pakistan’s Sindh province – the shining structure acts as a resting room for the patients’ families who arrive at the only major medical facility in the district. Ghulam Haider hailing from Nagarparkar had his daughter admitted into the hospital after a bout of cholera. That night he slept outside in the veranda by the ward. He found refuge inside the silver modular home after Karim – the caretaker of the Chandi Ghar space – mentioned to him that it was available for use throughout the day and night until his daughter would be cured.

Clean, versatile – and ahead of people’s perceptions

Structurally the Chandi Ghar is a modular, boxed design. The wastic blocks are manually compressed using the films and bamboo sticks for framed support. The same wastic module can be transformed into a table, chair, pillows, and a bed, depending on the needs of the household. As a structure it is energy efficient, too, shielding its users from the heat of the summer and the cold of the winter.However, in the aesthetics and health department, it is yet to catch up to the acquired perception of a livable house. Sugatullah, another visitor at the hospital, observes, “The first time I looked at it, I thought it was a chicken farm. I wouldn’t have known its purpose till I saw people use it as a resting room. I would only use this as a home if I had no other cheaper option.” Safety issues are also a concern, particularly the risk of a fire hazard; hence Nargis has banned cooking inside the Chandi Ghar. In terms of health, more research is required into the impacts of living with plastic.

Back in Karachi, I put forth the same question in regard to the visual presentation. Nargis counters with an analogy, “See, just like an old woman who adds basic makeup to look beautiful, similarly, all that the Chandi Ghar requires is a few internal touches and it will look good.”

Nargis does however complain about the lack of support from the government or the people of Karachi in general. She rants, “People in Karachi are not open to new ideas. Students and people don’t see it as clean. Sometimes they won’t even sit on it. Yes, students would come visit us but would not get involved with something as informal as this idea. They have this image of working towards the fantastic, the sophisticated, something that will land them a job. It’s a very backward mode of thinking. Doing something new requires dirtying your hands.” Today she hopes to collaborate with people outside of Pakistan in developing a better product.

What needs to change?

Nargis’ endeavors did not come without hurdles. She and her team combated forced expulsions from the rented space where they had set up their humble shop – expulsions purportedly driven by land grabbers, sometimes in collaboration with the incumbent government’s blessings.On the personal front, too, Nargis has had to sacrifice a lot. “It has taken 22 years of my life. My husband’s savings. A whole baggage of frustration, misery and anxiety. There was a time when I wanted to end my life but I had my husband and son.”

What needs to change I ask. “People’s thinking needs to change. We talk about an environmental catastrophe caused by the disposal of plastic. If people understood its value and sorted their waste it could be recycled into these blocks.” Referring to the temporal nature of housing she ends, “Isn’t it logical that when land is so expensive in cities, you build something that’s cost effective. Even in Katchi abadis (informal housing), you can have a Chandi Ghar. Since you don’t know if the land will be regularized [i.e. given legal cover and integrated with the civic services of the city] and when the time comes to vacate you dismantle the structure. Or if there’s an empty plot and the owner doesn’t want to build anything so he rents it out to you and you can use the wastic blocks as a temporary home, a farmer’s market, housing for construction workers and exhibitions.”

Outside of Gul Bahao’s humble research facility, a multistory apartment is under construction. While Chandi Ghar has the promise of being the seed to a more sustainable alternative, it is yet to be picked up as the mainstream technology for housing materials in Karachi. To paraphrase Nargis’ oft repeated proverb – “Necessity is the mother of invention” –, maybe Karachi’s city fathers have yet to recognize a number of necessities. Then, they might shift away from the practice of mining the Malir River bed (Karachi district’s monsoonal river) for river sand – a practice that is politically and economically profitable, but ecologically devastating – and let an alternative discourse emerge from the arising necessity to move onto more sustainable options.