Ecofeminism

The Bond for Environmental and Social Justice

All over the world, nature is being exploited, plundered, polluted. But how is this connected to patriarchy and our understanding of the human being? The Brazilian artist and researcher Mari Fraga looks at the environment from an ecofeminist perspective and finds an answer to these questions.

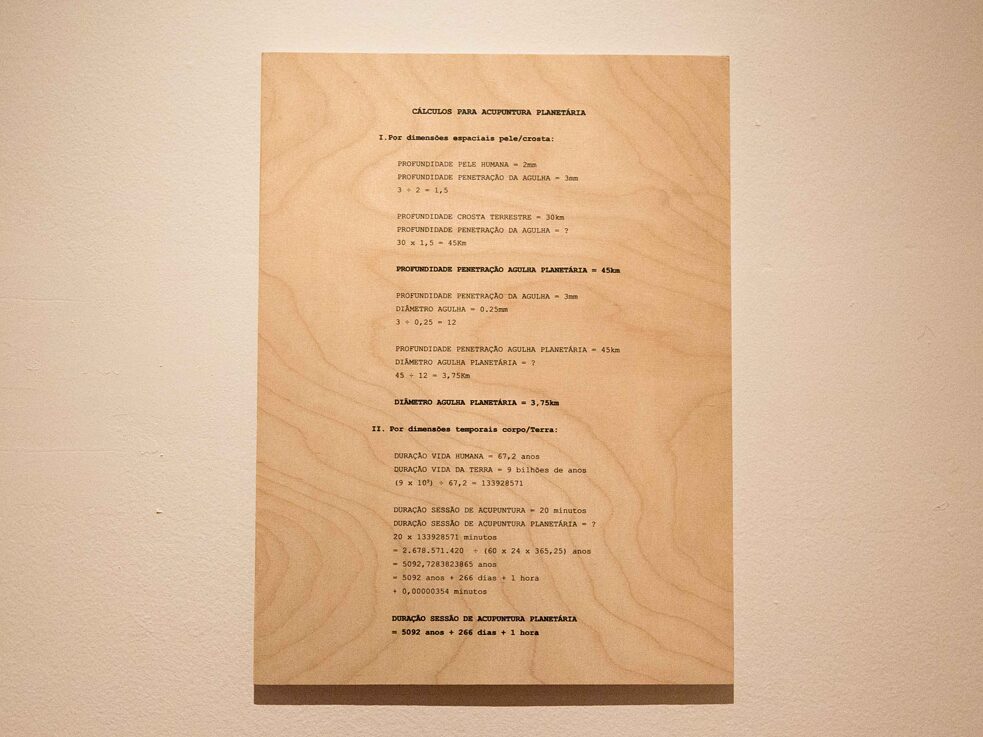

The connection between women and nature in opposition to a masculine notion of culture – that would like to see itself as hegemonic and universal – is an old historical construct. My artistic research dives into a body-earth analogy and takes the feminine body as an index of a broader association between non-white, non-Western and non-male people and nature. Two representations that connect the feminine and nature appear to me to be fundamental in this matter: Mother Earth and the Virgin Forest.

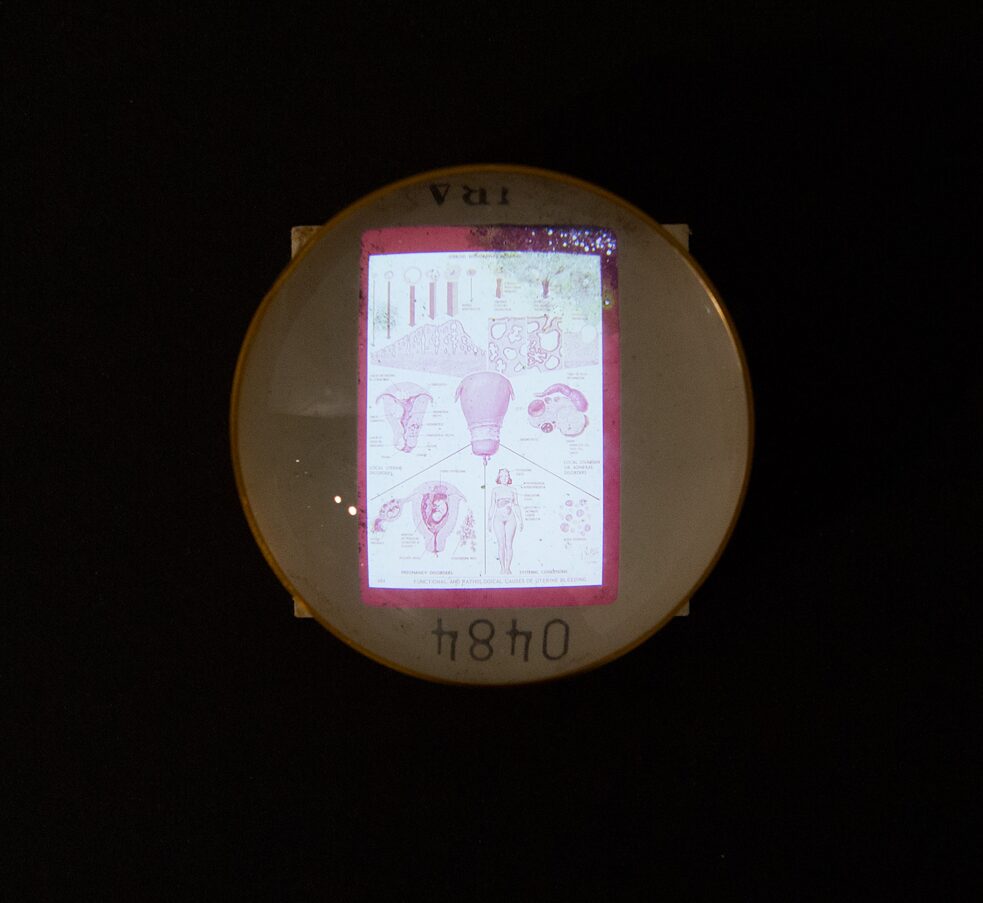

These two images are foundational to the myth of “Woman” as a social role in patriarchal culture, as well as to the myth of “Nature” as a resource to be exploited. While the Virgin Forest is pure, untouched, and isolated and works as a kind of natural stock for the feminine and nature, Mother Earth is the great nurturing entity, reproductive and available to serve men. I believe that the idealization of these two representations has its climax in the myth of the Virgin Mary, who is, paradoxically, mother and virgin, and, therefore, nurtures, reproduces, and serves at the same time as she remains pure. The Virgin Mary accentuates a feminine model which is impossible to achieve: one that dissociates reproduction and sexuality and idealizes the lack of autonomy of women regarding their own bodies.

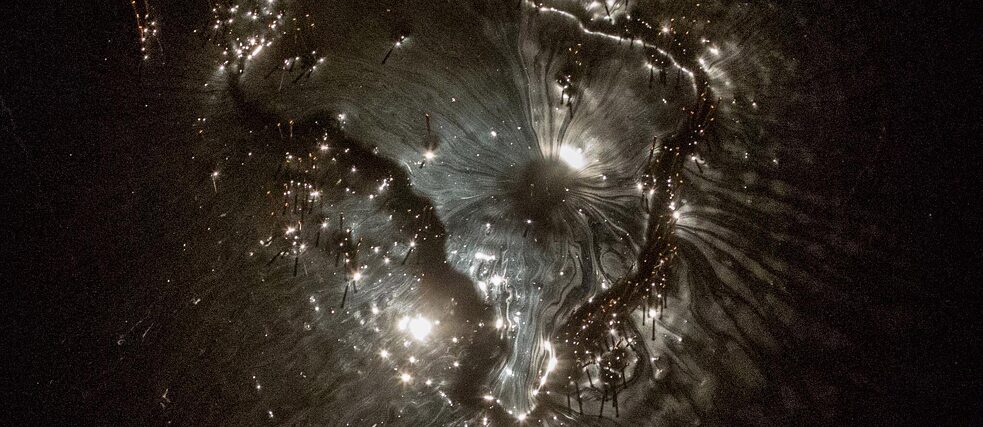

In this perspective, a forest that is at the same time virgin and productive seems a practical impossibility. But Indigenous communities and agroforestry practice teach us that nature can nurture us and remain preserved, although this has nothing to do with purity. The forest pulses sensuousness and fertility. A forest cannot be chaste: it materializes sexual interaction between multiple species. Plants, insects, animals and fungi are in permanent intercourse through flowers, fruits, seeds, nectar, and spores. The plural manifestation of nature's sexuality transcends our morals. Biology serves pleasure; pleasures serve the reproduction of life.

Anthropos as a Patriarchal Concept?

In the Anthropocene, scientists have been warning us that our impact on nature has achieved a geological scale. Humans are affecting complex natural systems, such as the climate, water cycles, biodiversity and even the composition of rocks. Anthropos was the elected term to describe humanity, but words are never neutral: every word hints at what it wants to reveal, as well as to hide.Since it was first proposed by natural scientists Crutzen and Stoermer in 2000, the political implications of the Anthropocene have been debated by well-known authors such as Bruno Latour, Isabelle Stengers, Donna Haraway, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Deborah Danowski, Peter Sloterdijk and Jason Moore. The Greek word anthropos has been used over centuries to indicate a human model based on the predominance of the mind – to the detriment of the corporeal realm – and carries a heritage of European, white, and patriarchal conceptions of what humanity and civilization should stand for.

I want to stress that this model of humanity has been systematically used to justify the subjugation and exploitation of other humans and territories throughout the planet. As Anne McClintock observes, in the past, the enterprise labelled “civilisation” was based on religious ideas, but also on scientific theories that, under the veil of “neutrality,” hid ideological, imperialist and economic motivations.

The anthropos of the Anthopocene is, therefore, a term that generalizes our species based on a certain model, and while the responsibility for its impacts is distributed equally among all human beings, it also implies that there is a biological reason for this way of dealing with nature. At the same time, the word anthropos hides the complex network of agencies that actually cause impacts, such as colonialism and capitalism, withits giant global corporations. Through the exploitation of land and of people's work, which have been treated as cheap or even free resources, these complex agencies have been plundering places like Latin America and Africa for five centuries, causing deforestation, industrial pollution, poverty, violence, and a long list of social, economic and ecological impacts.

Ni la tierra ni las mujeres somos territorio de conquista. Neither the land nor women are a territory of conquest.

Mujeres Creando - Bolivien

Creating a Different Understanding of Humans

If our society has been shaped by a racist, elitist, and sexist culture, the exploitation of nature, women and racialized people is based on the same assumptions. Authors like Maria Mies and Jason Moore have been emphatic in observing that the Western dualities that separate nature and society have always put women and non-Western cultures alongside nature, seeing them as closer to the sphere of the animal; primitive, uncontrolled and irrational.This is why, as Val Plumwood noticed in Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, ecofeminism has been met with some suspicion by many feminists, since it might reinforce the idea that women are reproductive animals that should remain controlled and domesticated. Feminists struggled for gender equality to gain the right to work, study and represent themselves. There is no doubt about the importance of this agenda, but Plumwood ponders whether, without structural changes, this might not result in simply accepting the masculine model for our society.

On the other hand, ecofeminism seeks to develop a different concept for human beings, one that is more conscious about human’s position as part of a whole and that embraces other types of knowledge and ways of living on this planet. Therefore, ecofeminism is an ally to Indigenous, anti-racist, and other social movements that fight for equality and justice.

The Bond between Woman and Nature

Thinking about Earth as a body changed my view of the world. Grasping the Earth beyond its function as a living organism or its symbol as an imaginary entity, such as in the “Gaia theory” postulated by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, or in Bruno Latour’s Facing Gaia or in Gaia the Intruder by Isabelle Stengers, or in Michel Serres’ Biogea, I use the analogy of Earth as a body to ask: what do we do with this body? Is the body a resource? Is the body a subject or an object?Thus taking the perspective that bodies and landscapes are social constructs, I realized that I am mostly interested in what is left out of the romantic myths. The mined, ravaged, exploited, objectified, maltreated, raped, and damaged lands and people become agents of insurgence and resistance in our times.

By situating women and racialized people as protagonists in the journey for a better future, ecofeminism creates a bond between the struggles for social and environmental justice. As Vandana Shiva states in an interview, there are important reasons for us to support the women-nature association beyond the stereotypical. While men, through privilege and power, were separated from the work of maintening life, women acquired knowledge through this work: an expertise that is deeply connected to nature.

Shiva concludes: “Women don't work, it was said. But this was the real work of maintaining and reproducing life. And by the task of doing these hundred jobs, women become multifunctional experts. They become water experts, seed experts, food experts, soil experts, birth experts, baby experts, diarrhea experts... Women, through life, develop an expertise. And that is why I say: when it comes to life, women are the experts. Not because our genes and biology make us so. But because leaving us to look after the sustenance of life has made us the experts for a bridge to the future, where we have to return to life, to considerations of how do you maintain life on this planet. “