Autumn ‘89

In any case, it wasn’t the bananas

While the leaves on the right and left of the Berlin Wall are turning autumnal, the Peaceful Revolution is beginning in the GDR. One year later, Germany is again one country.

The facts are familiar – but how did autumn 1989 really feel? On Monday demonstrations and the sale of chunks of the Wall to tourists.

On the traffic signs‘ absurdity

Tram tracks that run nowhere

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

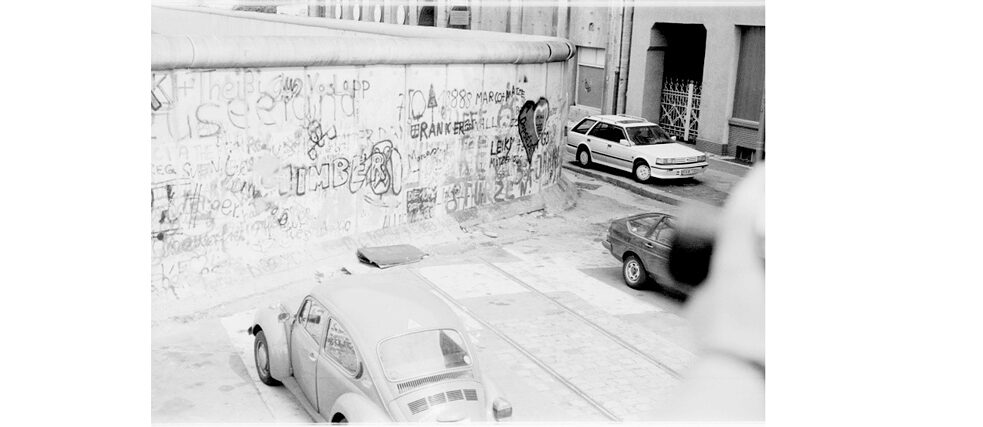

A resident parks her car in the middle of a Kreuzberger street and walks to her flat on the last few centimeters of West Berlin. What sort of traffic could hinder her here? She passes through the narrow passage between the front of the house and the wall. The VW-Beetle defies the absurdity of the Wall, as if it had suddenly placed itself in the car’s way during the drive. Next to it: streetcar tracks that end up nowhere, like a broken connection into a world behind graffiti and concrete. What this Kreuzberg idyll does not show are the more than 130 people who were shot while fleeing along this border.

Tram tracks that run nowhere

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

A resident parks her car in the middle of a Kreuzberger street and walks to her flat on the last few centimeters of West Berlin. What sort of traffic could hinder her here? She passes through the narrow passage between the front of the house and the wall. The VW-Beetle defies the absurdity of the Wall, as if it had suddenly placed itself in the car’s way during the drive. Next to it: streetcar tracks that end up nowhere, like a broken connection into a world behind graffiti and concrete. What this Kreuzberg idyll does not show are the more than 130 people who were shot while fleeing along this border.

The Wall has enclosed West Berlin since 13 August 1961, sometimes separating even from odd house numbers on the right and left sides of the street. The photo shows how it crosses the Berliners’ streets, how close it gets to their windows and how of necessity they live with it.

The border as a canvas

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

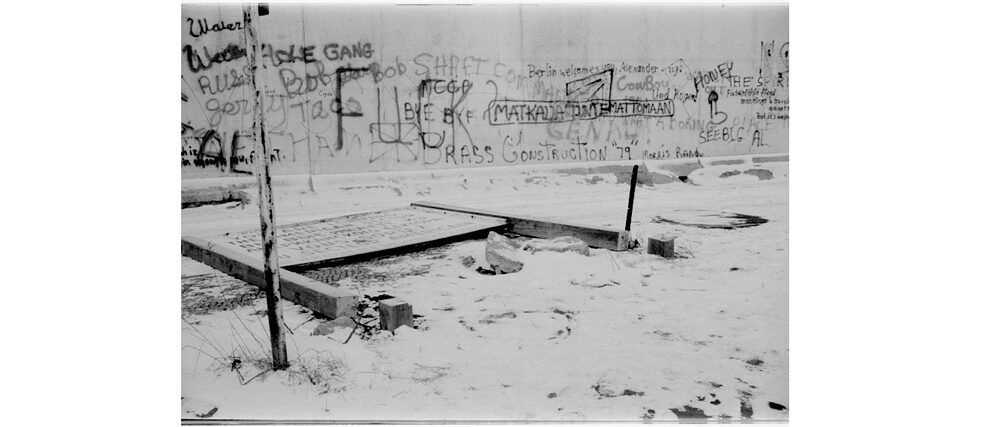

In contrast, West Berliners spray-paint the Wall, appropriating the border as a canvas. With their graffiti, they comment ironically on the West Berlin lifestyle - directly on the grey concrete that divides the city.

The border as a canvas

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

In contrast, West Berliners spray-paint the Wall, appropriating the border as a canvas. With their graffiti, they comment ironically on the West Berlin lifestyle - directly on the grey concrete that divides the city.

Four-language signboards lie fallen over in the snow along the Wall. They warn about the freedom or the danger of crossing the border. A few steps further it is clear that no crossing is possible here anyway. At this spot in Kreuzberg it says: "You are Leaving the American Sector". On the East Berlin side, a desolate restricted area runs along the Wall, keeping its own population away from the "peace border".

Revolution and candles

Demonstration in Wittenberge on 15 January 1990

| Photo: Horst Podiebrad © wir-waren-so-frei.de

"In any case, it wasn't the lack of bananas that got us onto the streets, but this constant feeling of fear and that we wanted to finally express our opinion freely," recalls Katharina Steinhäuser from Jena.

Demonstration in Wittenberge on 15 January 1990

| Photo: Horst Podiebrad © wir-waren-so-frei.de

"In any case, it wasn't the lack of bananas that got us onto the streets, but this constant feeling of fear and that we wanted to finally express our opinion freely," recalls Katharina Steinhäuser from Jena.

Every Monday after the prayers for peace in the churches of East Germany it becomes clearer that these numbers do not express the actual mood in the country. At the Monday demonstrations, citizens are demonstrating against the regime”. At first the mood is still tense and anxious", describes the contemporary witness, who herself was present in Jena - after all, all those present know exactly how the state deals with regime critics if there is any question. She describes this feeling as the fundamental tenor of the GDR: a humming or background noise of fear running in the background for years. "Of course, we were once happy, newly in love and young. But we were supposed to be shouting “Hurrah” all the time - and even that could be wrong. I remember a huge hopelessness"."Permanent, diffuse insecurity and fear of doing something wrong, of being imprisoned without rights and of being at the mercy of the state" clung to everyday situations and weapons. Katharina Steinhäuser remembers her first demonstration: "When I heard that thousands of people were demonstrating in Leipzig, I felt incredibly encouraged. I thought: Now you can no longer stand aside. Knowing how many there were already were gave us courage".

There’s an upbeat mood as they stand close by each other, dart off and light each other's candles. Although they are all too aware of the brutal attacks on demonstrators in the past, the consequences for their careers and their own lives, the demonstrators feel not only courage but also relief. After a "long period of depression", every shared step on the street feels like freedom. "Just demonstrating against the regime was a sudden change, to say: Here we go! We just plain won't keep quiet about anything that weighs us down any longer”.

Original banners of the Peaceful Revolution

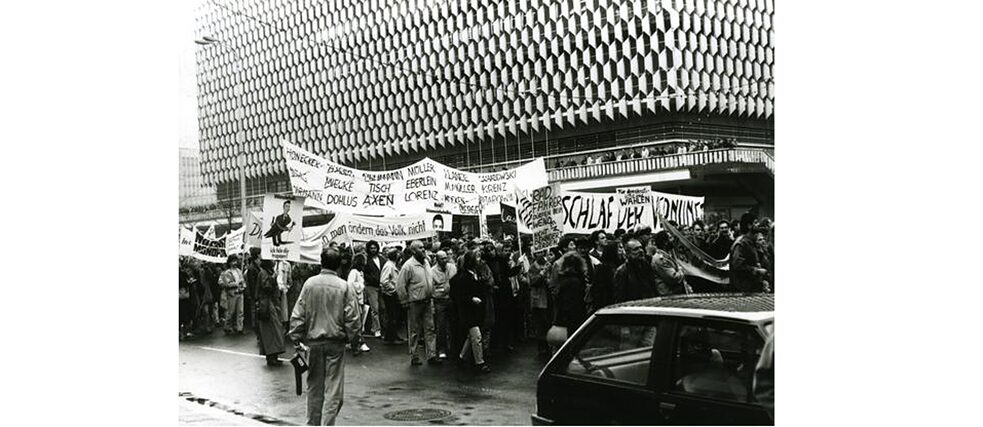

| Photo: Bernd Schmidt © wir-waren-so-frei.de

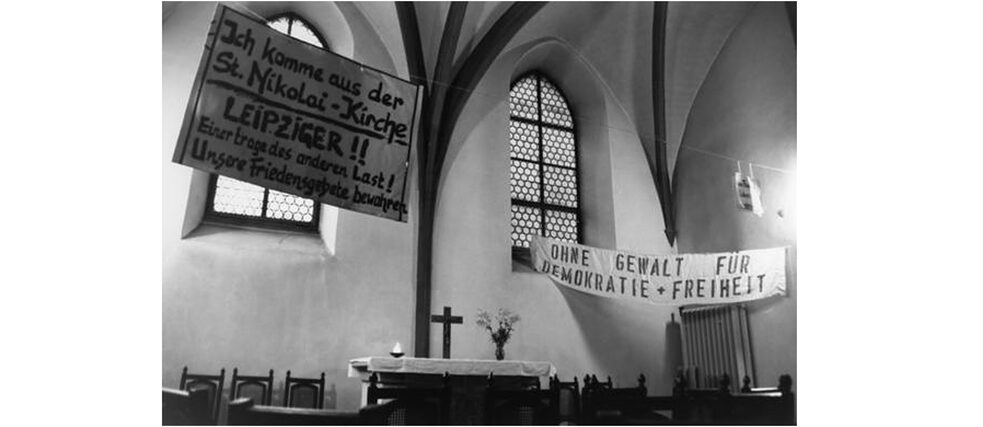

The citizens of Leipzig are protesting two days after the brutally suppressed protests on the occasion of the 40th anniversary celebration in Berlin. "No violence", demand six prominent Leipzig citizens of the SED functionaries and actually achieve that the police present, the military and the "working class combat groups" remain passive. The 300,000 demonstrators finally circumnavigate the entire city centre of Leipzig on the Ringstrasse - a turning point.

Original banners of the Peaceful Revolution

| Photo: Bernd Schmidt © wir-waren-so-frei.de

The citizens of Leipzig are protesting two days after the brutally suppressed protests on the occasion of the 40th anniversary celebration in Berlin. "No violence", demand six prominent Leipzig citizens of the SED functionaries and actually achieve that the police present, the military and the "working class combat groups" remain passive. The 300,000 demonstrators finally circumnavigate the entire city centre of Leipzig on the Ringstrasse - a turning point.

Call of the GDR opposition New Forum

| Photo: © Documentation Centre for Everyday Culture in the GDR

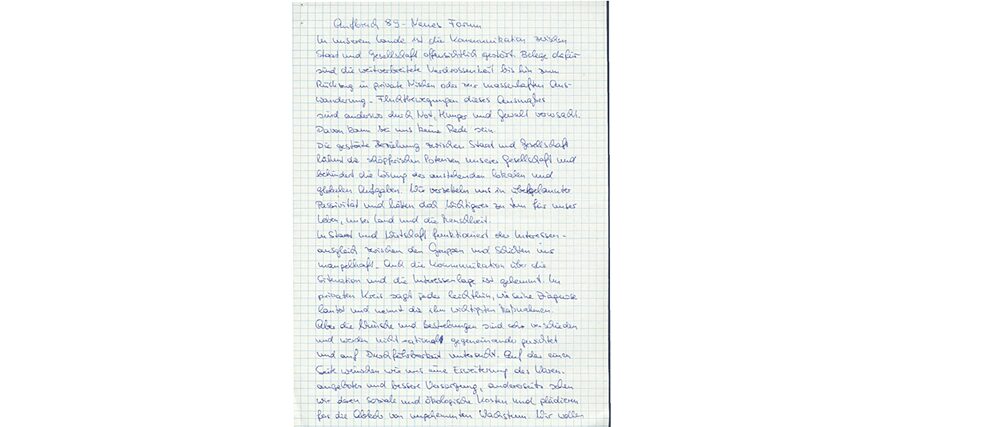

How does the opposition actually go about organising these protests? Someone secretly passes on a piece of paper, someone else hurries to copy it, the words on the calculating boxes look "innocent", almost like a transcript from school lessons - but in fact they are deeply political. With these loose sheets of paper the call of the new forum spreads within a few days. For the first time in the history of the GDR, opposition members seek official approval as a political group. These are the hours of repositioning - in a few days thousands of citizens will sign the initiative.

Call of the GDR opposition New Forum

| Photo: © Documentation Centre for Everyday Culture in the GDR

How does the opposition actually go about organising these protests? Someone secretly passes on a piece of paper, someone else hurries to copy it, the words on the calculating boxes look "innocent", almost like a transcript from school lessons - but in fact they are deeply political. With these loose sheets of paper the call of the new forum spreads within a few days. For the first time in the history of the GDR, opposition members seek official approval as a political group. These are the hours of repositioning - in a few days thousands of citizens will sign the initiative.

Berlin Alexanderplatz – live on GDR-TV

Alexanderplatz Demonstration, Berlin, November 4, 1989

| Photo: Thomas Wiesenack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

"It's as if someone had thrown open the windows," says author Stefan Heym, thus capturing the mood of the 500,000 who, on November 4 at Berlin's Alexanderplatz, are calling on the GDR leadership to reorient itself politically. The artists of various East Berlin theatres are calling for this demonstration, waiting for the demonstrators. Meanwhile, people stand close together in the underground corridors - sandwiched between their knees: their banners still rolled up and their posters held downwards. As in the weeks before in Leipzig and elsewhere, they are imaginative, ironic and express the widest variety of political demands for a reform of socialism in the GDR. With slogans like "Mit dem Gesicht zum Volk" ("With your face to the people") and "130000 Stasiknechte haben keine Sonderrechte" ("130000 Stasi yes-mens have no special rights"), the demonstrators address the GDR leadership directly. During the first approved demonstration critical of the regime, the citizens recapture the street - and the state permits this action. Freedom and change cast a spell over the people. More than 20 speakers, including official representatives of GDR policies, analyse the situation of their country and make their demands. It's quiet: Probably demonstrators in the GDR have never listened so attentively to a rally.

Alexanderplatz Demonstration, Berlin, November 4, 1989

| Photo: Thomas Wiesenack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

"It's as if someone had thrown open the windows," says author Stefan Heym, thus capturing the mood of the 500,000 who, on November 4 at Berlin's Alexanderplatz, are calling on the GDR leadership to reorient itself politically. The artists of various East Berlin theatres are calling for this demonstration, waiting for the demonstrators. Meanwhile, people stand close together in the underground corridors - sandwiched between their knees: their banners still rolled up and their posters held downwards. As in the weeks before in Leipzig and elsewhere, they are imaginative, ironic and express the widest variety of political demands for a reform of socialism in the GDR. With slogans like "Mit dem Gesicht zum Volk" ("With your face to the people") and "130000 Stasiknechte haben keine Sonderrechte" ("130000 Stasi yes-mens have no special rights"), the demonstrators address the GDR leadership directly. During the first approved demonstration critical of the regime, the citizens recapture the street - and the state permits this action. Freedom and change cast a spell over the people. More than 20 speakers, including official representatives of GDR policies, analyse the situation of their country and make their demands. It's quiet: Probably demonstrators in the GDR have never listened so attentively to a rally. Alexanderplatz Demonstration in Berlin on November 4, 1989

| Photo: Merit Schambach © wir-waren-so-frei.de

This critical thinking reverberates beyond the square to the Republic's fold-out sofas: GDR television is broadcasting live, thus demonstrating the government's willingness to engage in dialogue. We do not know whether this dialogue would have taken place in the end and whether the GDR would have developed into a democratic country, because five days later the Berlin Wall fell. The internal demand for reforms was now under pressure from the open border. While hundreds of thousands went to the West, the GDR dissolved from within.

Alexanderplatz Demonstration in Berlin on November 4, 1989

| Photo: Merit Schambach © wir-waren-so-frei.de

This critical thinking reverberates beyond the square to the Republic's fold-out sofas: GDR television is broadcasting live, thus demonstrating the government's willingness to engage in dialogue. We do not know whether this dialogue would have taken place in the end and whether the GDR would have developed into a democratic country, because five days later the Berlin Wall fell. The internal demand for reforms was now under pressure from the open border. While hundreds of thousands went to the West, the GDR dissolved from within. Demonstration in Berlin on 4 November 1989

| Photo: Hubert Link © Bundesarchiv / Wikimedia

Just how conscious they are of the political and historical worth of their actions is shown by a group in the midst of the crowd: at the end of the rally, they collect the posters and deposit them in front of the Museum für Deutsche Geschichte, the GDR's official historical museum.

Demonstration in Berlin on 4 November 1989

| Photo: Hubert Link © Bundesarchiv / Wikimedia

Just how conscious they are of the political and historical worth of their actions is shown by a group in the midst of the crowd: at the end of the rally, they collect the posters and deposit them in front of the Museum für Deutsche Geschichte, the GDR's official historical museum.

With immediate effect

"Up until the end I didn't believe the Wall would open," recalls Katharina Steinhäuser. "Friends from Bonn visited us once. When we were standing at the station, my little daughter said, "Next time we'll go there and visit them", and I replied, "That's never going to happen". I'd never have thought that the Wall would come down - and it came down relatively quickly". She relates how central the desire for freedom was, for the possibility of travelling and speaking freely - and that most did not long for the end, but for a reform of the GDR."When does it take effect?" It feels like a query on the blackboard at school: the questions from journalists* seem to surprise Günther Schabowski, he answers awkwardly, perhaps even hopes that someone will whisper something to him after he has announced the new travel regulations. "To the best of my knowledge, it's immediately, immediately". By mistake, the Berlin SED leader declares the immediate fall of the Berlin Wall, a few minutes later the news spreads that the border is open!

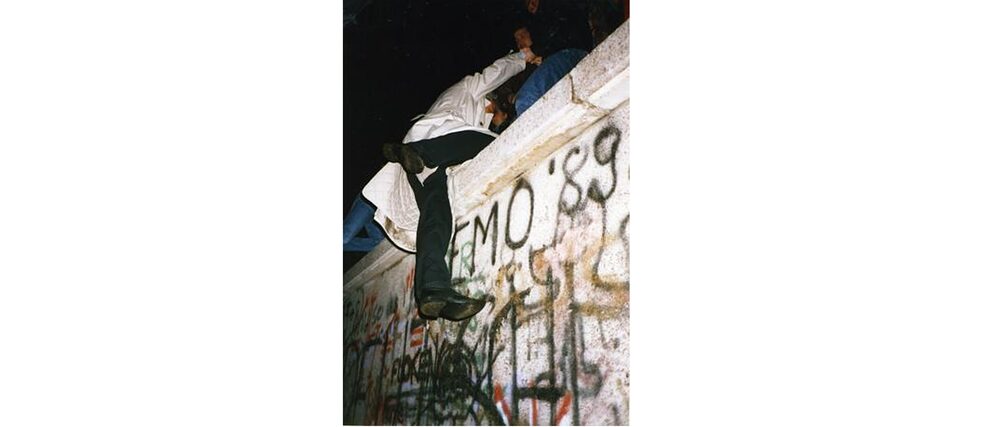

With sparklers on the Berlin Wall: Brandenburg Gate on 10 November 1989

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

The extreme tension of the past few days is discharging. Thousands of East Berliners are walking or getting into their cars to drive to the Wall. Uncertainty prevails here: on the one hand, the border has been declared open, on the other, the border officials are not informed. For the time being, the barriers remain down and the border is closed. Shortly after 9 p.m., the first GDR citizens are allowed to leave the country; the officials invalidate their passports and thus revoke their citizenship. "I am often asked why, as the daughter of a pastor, I did not simply apply for an exit visa. But I would have had to leave my family behind. We didn't even consider that the state would dissolve, but simply wanted to drive over, make a trip and be allowed to come back again." The stamps in the passports reflect this collective fear of expatriation, which Katharina Steinhäuser will continue to feel for a long time to come. "To me, going to Thuringia and seeing the border post or hearing someone criticise a politician is still something special. At such moments, I still lower my voice and don't know if I can really trust its being possible now".

With sparklers on the Berlin Wall: Brandenburg Gate on 10 November 1989

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

The extreme tension of the past few days is discharging. Thousands of East Berliners are walking or getting into their cars to drive to the Wall. Uncertainty prevails here: on the one hand, the border has been declared open, on the other, the border officials are not informed. For the time being, the barriers remain down and the border is closed. Shortly after 9 p.m., the first GDR citizens are allowed to leave the country; the officials invalidate their passports and thus revoke their citizenship. "I am often asked why, as the daughter of a pastor, I did not simply apply for an exit visa. But I would have had to leave my family behind. We didn't even consider that the state would dissolve, but simply wanted to drive over, make a trip and be allowed to come back again." The stamps in the passports reflect this collective fear of expatriation, which Katharina Steinhäuser will continue to feel for a long time to come. "To me, going to Thuringia and seeing the border post or hearing someone criticise a politician is still something special. At such moments, I still lower my voice and don't know if I can really trust its being possible now".

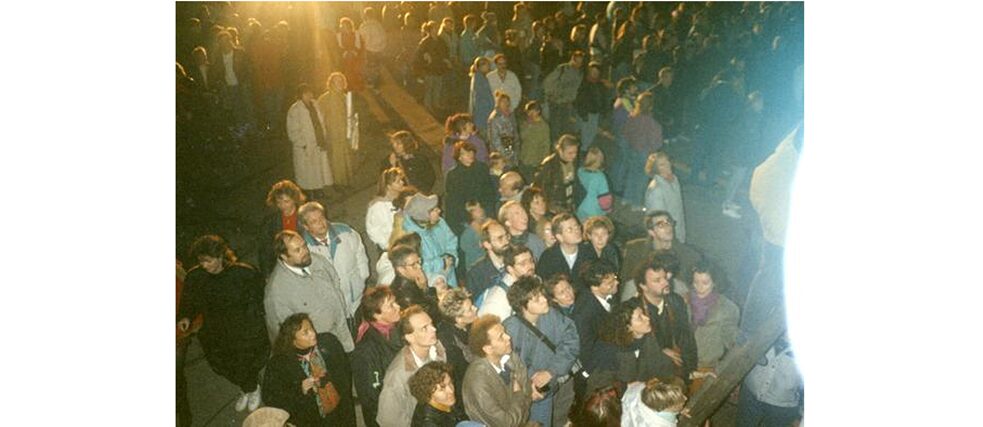

On the border: Brandenburg Gate, Berlin 10 November 1989

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

On Berlin's night-time streets, relief and euphoria mix with curiosity and the feeling that something impossible has happened. At midnight all border crossings in the city area are open. The atmosphere is exuberant and boisterous, pubs serve free beer, people from East and West euphorically embrace each other, applaud each other, help each other on the masonry that separated them for decades, and dance. They are the giddiest images of that time. Despite all the problems that will come later, they still shape the narrative of unity today.

On the border: Brandenburg Gate, Berlin 10 November 1989

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

On Berlin's night-time streets, relief and euphoria mix with curiosity and the feeling that something impossible has happened. At midnight all border crossings in the city area are open. The atmosphere is exuberant and boisterous, pubs serve free beer, people from East and West euphorically embrace each other, applaud each other, help each other on the masonry that separated them for decades, and dance. They are the giddiest images of that time. Despite all the problems that will come later, they still shape the narrative of unity today. On the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate: Berlin, 10 November 1989

| Photo: Hartmut Kieselbach © wir-waren-so-frei.de

A contemporary witness photographing the relaxed people at the Wall remembers: "And when my eyes got used to the darkness, I noticed the Vopos [People's Police] in their dark green uniforms. They stood motionless along the Wall at a distance of two arm's lengths, like wax figures, and seemed to be observing us. What a contrast".

On the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate: Berlin, 10 November 1989

| Photo: Hartmut Kieselbach © wir-waren-so-frei.de

A contemporary witness photographing the relaxed people at the Wall remembers: "And when my eyes got used to the darkness, I noticed the Vopos [People's Police] in their dark green uniforms. They stood motionless along the Wall at a distance of two arm's lengths, like wax figures, and seemed to be observing us. What a contrast".

The first day "over there"

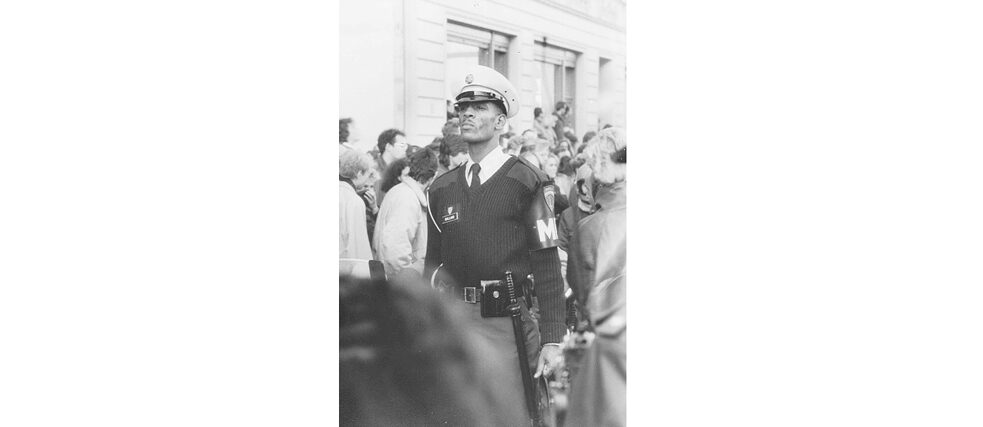

On November 10, the American military policeman stoically watches over his Allied border checkpoint "Checkpoint Charlie".

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

Where Soviet and American tanks have faced each other since the Wall was built, the media are there live as East Berliners stream towards West Berlin. They want to "have a look". The older ones want to stroll across the Kurfürstendamm and see friends and relatives once again. The younger ones discover new localities where the East Berlin city map has hitherto only shown a white area. Meanwhile, many office chairs remain empty, the machines in the factories are abandoned as the workers visit West Berlin - regular work is out of the question. Some, however, do not wish to take part in the commotion or hold "the position" for political reasons.

On November 10, the American military policeman stoically watches over his Allied border checkpoint "Checkpoint Charlie".

| Photo: © Andreas Ludwig

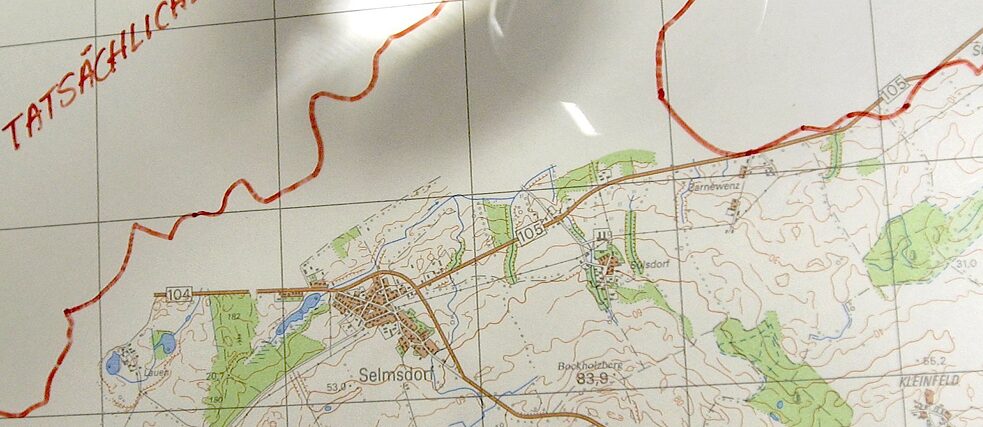

Where Soviet and American tanks have faced each other since the Wall was built, the media are there live as East Berliners stream towards West Berlin. They want to "have a look". The older ones want to stroll across the Kurfürstendamm and see friends and relatives once again. The younger ones discover new localities where the East Berlin city map has hitherto only shown a white area. Meanwhile, many office chairs remain empty, the machines in the factories are abandoned as the workers visit West Berlin - regular work is out of the question. Some, however, do not wish to take part in the commotion or hold "the position" for political reasons. Map forged by state security. This was to prevent the GDR population from receiving accurate information about the border.

| Photo (detail): Tim Brakemeier © dpa – Fotoreport

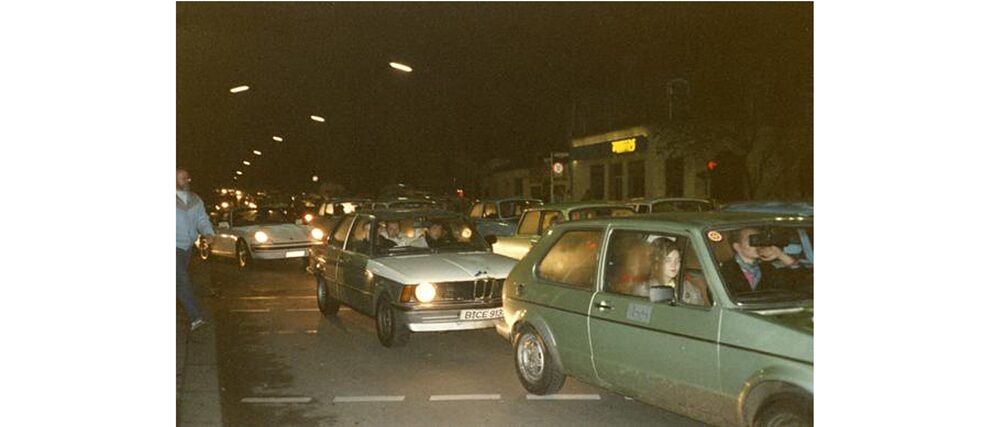

East Berliner "Trabanten" (“Trabbis”) move among Golfs and BMWs through the nightly traffic jam on West Berlin's streets. A few hours after the evening news on western TV, West Berlin resembles a huge street festival. "It's a mix of different feelings. On my first trip it was of course a big surprise to see what everything looks like. I'm not exactly blind and I realised that there are other problems above and beyond the Wall; that our current system leaves people behind or creates new problems. Everything that was A was now Z. Everything that was important was now unimportant and vice versa", reminisces Katharina Steinhäuser about her first visit to West Berlin.

Map forged by state security. This was to prevent the GDR population from receiving accurate information about the border.

| Photo (detail): Tim Brakemeier © dpa – Fotoreport

East Berliner "Trabanten" (“Trabbis”) move among Golfs and BMWs through the nightly traffic jam on West Berlin's streets. A few hours after the evening news on western TV, West Berlin resembles a huge street festival. "It's a mix of different feelings. On my first trip it was of course a big surprise to see what everything looks like. I'm not exactly blind and I realised that there are other problems above and beyond the Wall; that our current system leaves people behind or creates new problems. Everything that was A was now Z. Everything that was important was now unimportant and vice versa", reminisces Katharina Steinhäuser about her first visit to West Berlin. Traffic jam in West Berlin 9 November 1989, near Kurfürstendamm

| Photo: Fumiko Matsuyama © wir-waren-so-frei.de

In the coming days, West Berliners will also be taking a look at East Berlin. Initially, they will still be applying for day visits and permits to obtain a visa, will be passing border controls and will have to exchange money. But because no one wants to control any more, wants to endure the anger or mockery of those intending to travel, the curious soon view the dissolution of any kind of order un-bureaucratically. Some are said to have succeeded in entering the country by presenting a fare ticket instead of ID, while others stop at the Wall and only now believe that it is really open.

Traffic jam in West Berlin 9 November 1989, near Kurfürstendamm

| Photo: Fumiko Matsuyama © wir-waren-so-frei.de

In the coming days, West Berliners will also be taking a look at East Berlin. Initially, they will still be applying for day visits and permits to obtain a visa, will be passing border controls and will have to exchange money. But because no one wants to control any more, wants to endure the anger or mockery of those intending to travel, the curious soon view the dissolution of any kind of order un-bureaucratically. Some are said to have succeeded in entering the country by presenting a fare ticket instead of ID, while others stop at the Wall and only now believe that it is really open. Man with camera at the open sector border

| Photo: Andreas Ludwig

Man with camera at the open sector border

| Photo: Andreas Ludwig

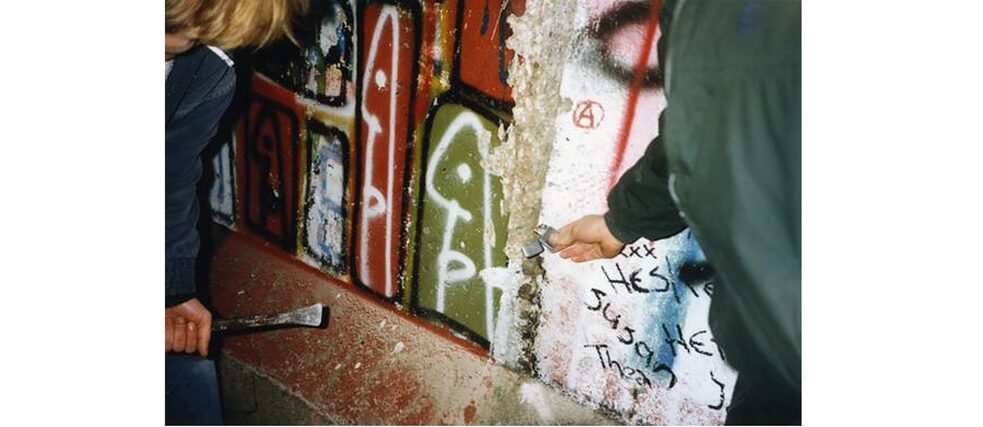

How the Wall became mere material

"Mauerspecht" ("Wall Woodpecker"), Berlin, November 1989, between Reichstag and Potsdamer Platz

| Photo: Jürgen Lottenburger © wir-waren-so-frei.de

Regular blows resound, from a distance they sound like a festival of uninhibited DIY-ers. But in the weeks following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the hammer - actually the symbol of the workers on the GDR flag - is striking thousands of times against the concrete.

"Mauerspecht" ("Wall Woodpecker"), Berlin, November 1989, between Reichstag and Potsdamer Platz

| Photo: Jürgen Lottenburger © wir-waren-so-frei.de

Regular blows resound, from a distance they sound like a festival of uninhibited DIY-ers. But in the weeks following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the hammer - actually the symbol of the workers on the GDR flag - is striking thousands of times against the concrete.

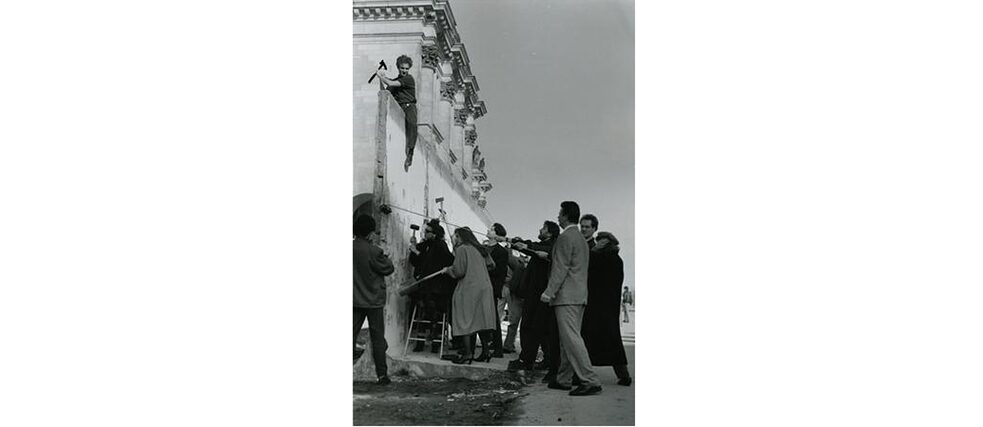

For years, the Wall has been a real structural barrier for both sides of the city, cutting off tram tracks, limiting possibilities, relationships and routes. At the same time, however, the Wall was also a symbol of the Cold War, of the either/or of affiliation with the political blocs - either the reactionary politics of consumption or the socialist absence of freedom. It symbolised an order that does not tolerate any nuances and confronts the citizens on both sides with their own powerlessness. On these November days they also free themselves physically.

First "Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers"), Berlin, 10 November 1989, Brandenburg Gate

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

With hammer and chisel they not only put an end to the physical unavoidability of the Wall, but also destroy the symbolic level of concrete - depriving it of its political authority. At the new destination, the Berlin Wall, people are hacking away at it, working their way through it. The hammer blows of the "Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers") continue for weeks. In the end, the concrete is again what it was before it was poured into form: mere material. It ends up as filler in road construction.

First "Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers"), Berlin, 10 November 1989, Brandenburg Gate

| Photo: Monika Waack © wir-waren-so-frei.de

With hammer and chisel they not only put an end to the physical unavoidability of the Wall, but also destroy the symbolic level of concrete - depriving it of its political authority. At the new destination, the Berlin Wall, people are hacking away at it, working their way through it. The hammer blows of the "Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers") continue for weeks. In the end, the concrete is again what it was before it was poured into form: mere material. It ends up as filler in road construction.

"Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers") at the Reichstag, Berlin in March 1990

| Photo: Gabriele Greaney © wir-waren-so-frei.de

"Mauerspechte" ("Wall Woodpeckers") at the Reichstag, Berlin in March 1990

| Photo: Gabriele Greaney © wir-waren-so-frei.de