The Families of Rosenstrasse

“So many women — that was a real demonstration!”

At the center of the Rosenstrasse Protest are the families that the Gestapo tore apart — and the wives and mothers who fought back. These are some of their stories.

By Kathrin Engler

The Abraham Family

This protest grew, the women protested day and night facing incredible danger. Goebbels now faced something unheard of, an anti-Nazi street demonstration. [...] There they were, my brave mother amongst them, unarmed women with guns pointed at them, no one moved.

Katrin Balaban

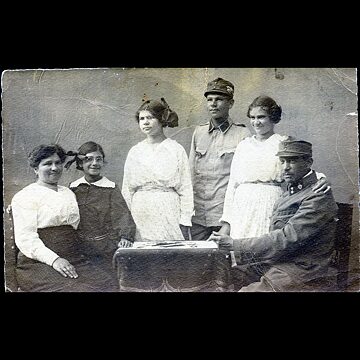

Anni Abraham

| Photo: Courtesy of Katrin Balaban

Everything changed for the Abraham family as soon as the Nazis came to power. Jaques lost his job, and Anni worked several jobs to support the family.

Anni Abraham

| Photo: Courtesy of Katrin Balaban

Everything changed for the Abraham family as soon as the Nazis came to power. Jaques lost his job, and Anni worked several jobs to support the family.Anni Abraham came under increasing pressure to divorce Jaques as did most women in “mixed” marriages, some of whom complied. However, Anni stood by her husband. Jaques and Anni’s marriage fell under the Nazi category of “priviligierte Mischehe” (English: “privileged intermarriage”). Because of this, Jaques was not immediately deported to a concentration camp but had to do forced labor. This “privileged” status ended in February 1943 when Joseph Goebbels decided to round up the remaining Jews living in Berlin — including those in “mixed marriages” — in order to deport them to death camps.

Jaques Abraham was arrested and kept in a former Jewish community center on Rosenstrasse. Anni was one of the first women to show up there, demanding her husband’s release. The demonstration grew, and protesting women remained in front of the building day and night despite the incredible danger. Goebbels first ordered the protestors to be removed, but even with the SS’s guns pointed at them, the peaceful protestors didn’t budge. Afraid this might cause further unrest, undermine the claim that all Germans were united in a Volksgemeinschaft (Nazi term for racial community), and draw attention to the deportation of Jews, Goebbels got Hitler’s approval to release the men.

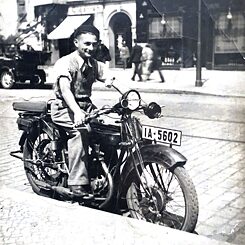

Jaques Abraham on his motorcycle

| Photo: Courtesy of Katrin Balaban

Jaques Abraham survived the Nazi regime and started an ambulance service after the end of the war. Even living in the American sector of Berlin with a flourishing business, Jaques worried about the Russians, especially after the Berlin blockade began in 1948. The Abrahams left Germany in September 1949 and immigrated to the U.S., where they settled in Brooklyn, New York. Katrin later married Larry Balaban, a Jewish American.

Jaques Abraham on his motorcycle

| Photo: Courtesy of Katrin Balaban

Jaques Abraham survived the Nazi regime and started an ambulance service after the end of the war. Even living in the American sector of Berlin with a flourishing business, Jaques worried about the Russians, especially after the Berlin blockade began in 1948. The Abrahams left Germany in September 1949 and immigrated to the U.S., where they settled in Brooklyn, New York. Katrin later married Larry Balaban, a Jewish American.

The Gottschalk Family

Meta and Michael are already asleep.

Joachim Gottschalk

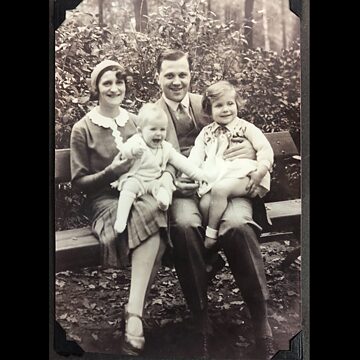

Joachim Gottschalk with his son Michael

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

The tragic fate of the Gottschalk family is an example of how far-reaching Nazi retribution could be. Actor Joachim Gottschalk (born 1904) was one of the most famous and popular actors in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s.

Joachim Gottschalk with his son Michael

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

The tragic fate of the Gottschalk family is an example of how far-reaching Nazi retribution could be. Actor Joachim Gottschalk (born 1904) was one of the most famous and popular actors in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s.In 1930, he married actress Meta Wolff, who born Jewish, converted to Protestantism after their marriage. In 1933, the same year that Hitler came to power, their son Michael was born. Despite her conversion, Meta was still considered Jewish according to Nazi law and was prohibited from working as an actress. In May 1936, Nazi officials attempted to remove Gottschalk from the theater, but he was able to star in a number of films.

In 1937, the province of Hesse-Nassau sent a letter to the director of the Frankfurt theater to express outrage that Joachim played a part in the first “Gau Culture Week” and demanded his removal due to his “Jewish relations.” He was fired by the theater in January 1938, but by May of 1941, Gottschalk had built an impressive film career that distinguished him as one of the most successful actors in the country. Goebbels, upon hearing that Joachim was to star in Die Goldene Stadt (The Golden City), was shocked that the famous actor remained married to a Jewish woman and ordered that Gottschalk should separate from his Jewish wife. When Joachim refused, Goebbels ordered that the actor be blacklisted until he divorced.

Joachim Gottschalk and Meta Wolff with their son Michael

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

On November 6, 1941, Joachim and Meta ended their own and their son’s lives. Nazi censorship attempted to keep the family’s death a secret but despite explicit prohibitions, Gottschalk’s colleagues attend his funeral. Two weeks later, Hitler instructed Goebbels to take a “forceful policy against the Jews.” Regarding “mixed marriages,” Goebbels must “follow a somewhat reserved course of action,” particularly for “those in artists’ circles.” Goebbels and Hitler tried to use tactics that would not stir popular unrest and damage Hitler’s image.

Joachim Gottschalk and Meta Wolff with their son Michael

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

On November 6, 1941, Joachim and Meta ended their own and their son’s lives. Nazi censorship attempted to keep the family’s death a secret but despite explicit prohibitions, Gottschalk’s colleagues attend his funeral. Two weeks later, Hitler instructed Goebbels to take a “forceful policy against the Jews.” Regarding “mixed marriages,” Goebbels must “follow a somewhat reserved course of action,” particularly for “those in artists’ circles.” Goebbels and Hitler tried to use tactics that would not stir popular unrest and damage Hitler’s image.

The Holzer Family

People flowed back and forth. The street was full. This short little street was black with people. They were like a wave, and they moved like a body, a swaying body.

Elsa Holzer

Rudi Holzer stemmed from a family of secular Jews who baptized their children as Catholics. Rudi was active in the Catholic church, serving as a choir boy and acolyte. At age 12, his aim was to become a pedagogical monk. However, he changed his mind as he grew older, since he “had an eye for the ladies” and wanted to marry.

At the start of World War I, Rudi was 17 years old and volunteered for the Austrian Army to prove his “patriotic worth.” After the war, Rudi finished his training in printing and typesetting. Unable to agree with his father on how to run the growing family business, he moved to Berlin.

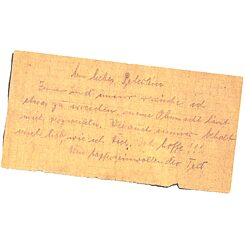

Elsa Holzer asked an officer to give her husband Rudi a sandwich while he was detained on Rosenstrasse. Inside the sandwich, she had hidden a note: “Dear Rudi, All the best. I love you forever. Yours, Elsa.”

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

Rudi and Elsa married in 1929, paying little attention to politics and the evolving dangerous political climate in Germany. With Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938 and as residents of Rudi’s village turned deeply antisemitic, the couple discussed immigration. Under Nazi rule, two of Rudi’s sisters were abandoned by their “Aryan” husbands. In Berlin Rudi’s Jewish heritage had remained undetected until a postcard arrived in 1939, inquiring: “Is Annegret Schwarz of Sankt Johann your sister?” Rudi was then officially identified as Jewish and fined as a criminal for not having registered as Jewish. “I didn’t know I was Jewish,” he told police. “All my documents are Catholic.”

Elsa Holzer asked an officer to give her husband Rudi a sandwich while he was detained on Rosenstrasse. Inside the sandwich, she had hidden a note: “Dear Rudi, All the best. I love you forever. Yours, Elsa.”

| Photo: Courtesy of the Rosenstrasse Foundation

Rudi and Elsa married in 1929, paying little attention to politics and the evolving dangerous political climate in Germany. With Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938 and as residents of Rudi’s village turned deeply antisemitic, the couple discussed immigration. Under Nazi rule, two of Rudi’s sisters were abandoned by their “Aryan” husbands. In Berlin Rudi’s Jewish heritage had remained undetected until a postcard arrived in 1939, inquiring: “Is Annegret Schwarz of Sankt Johann your sister?” Rudi was then officially identified as Jewish and fined as a criminal for not having registered as Jewish. “I didn’t know I was Jewish,” he told police. “All my documents are Catholic.”Rudi lost his job, and the tenants of their building refused to let them into the basement air raid shelter because the air the Holzers breathed out they would not breathe in. Elsa’s family shunned them, pressuring Elsa to divorce “her Jew.” Rudi was compelled into forced labor. Elsa was called into the foreboding SS headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse for threats and humiliations about her marriage. Left waiting for further interrogations, heart pounding, she bolted for home at the thought that perhaps while she was away the Gestapo was taking her husband.

During the “final round-up” of intermarried Jews in Berlin (named “Factory Action” after the war), Rudi was taken to Rosenstrasse. As soon as Elsa found out where her husband was detained, she set off and was surprised to see a large crowd of women waiting in the cold: “People flowed back and forth. The street was full. This short little street was black with people. They were like a wave, and they moved like a body, a swaying body.” Some remembered armed guards shouting, “Clear the street or we’ll shoot!” Elsa recalled an open jeep-like vehicle scattering them with its approach and emitting sounds like gunfire.

The women wanted to show Jewish family members that they would still not abandon them. With the help of a police officer, Elsa was able to send Rudi a message written on paper and placed in a sandwich. She recalled the “real joy” that she felt in realizing he would know she was there. On March 8, Rudi was released. “We acted from the heart and look what happened,” Elsa said.

The Kuhn Family

On the walls next to the store was ‘Jew’ and then the star. [...] What struck me then [...] was that they were written in red letters, and it was dripping still, the red was dripping like blood.

Rita Kuhn

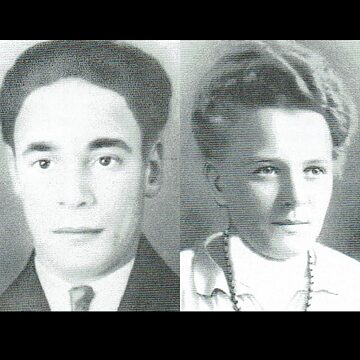

Fritz and Frieda Kuhn

| Photo: Courtesy of Ruth Wiseman

Fritz Kuhn was born Jewish, and his wife Frieda converted to Judaism in the 1920s. The family belonged to Berlin’s Jewish community. Rita Jenny Kuhn (born 1927), her younger brother Hans, and her parents Fritz and Frieda all survived the Nazi period, but they each endured hardships as a result of the Nuremberg Laws. Since Frieda was born into a Lutheran family and converted to Judaism before marrying Fritz, she was considered non-Jewish under the Nuremberg Laws.

Fritz and Frieda Kuhn

| Photo: Courtesy of Ruth Wiseman

Fritz Kuhn was born Jewish, and his wife Frieda converted to Judaism in the 1920s. The family belonged to Berlin’s Jewish community. Rita Jenny Kuhn (born 1927), her younger brother Hans, and her parents Fritz and Frieda all survived the Nazi period, but they each endured hardships as a result of the Nuremberg Laws. Since Frieda was born into a Lutheran family and converted to Judaism before marrying Fritz, she was considered non-Jewish under the Nuremberg Laws.The Kuhns remained in Berlin throughout the war years. Fritz Kuhn lost his banking job and was required to do forced labor, often working 11 hours daily. Their daughter Rita was assigned factory work as a forced laborer.

On the morning of February 27, 1943, Rita had just reported for work when the SS showed up yelling, “Juden raus!” (“Jews out!”). Rita and other Jewish workers were loaded into a truck and taken to a collection point. Fortunately, Rita was sent back home by an SS officer after spending the entire day locked in a building with thousands of other women.

A week later, Rita with her father Fritz and brother Hans were separated from her mother Frieda when the three were arrested while collecting ration cards. As before, Rita waited in a locked room that slowly filled with other German Jews. From there, the Kuhns were taken to Rosenstrasse.

Hans and Rita Kuhn

| Photo: Courtesy of Ruth Wiseman

It was there that Rita learned of the protests taking place just outside their building. Rita spent one night at Rosenstrasse with her father and brother before being released the following day. Rita was reassigned to work at a Berlin railway station, where she worked until the end of the war. Fritz, too, was reassigned to forced labor.

Hans and Rita Kuhn

| Photo: Courtesy of Ruth Wiseman

It was there that Rita learned of the protests taking place just outside their building. Rita spent one night at Rosenstrasse with her father and brother before being released the following day. Rita was reassigned to work at a Berlin railway station, where she worked until the end of the war. Fritz, too, was reassigned to forced labor.Rita immigrated to the United States in 1948. Her family was supposed to follow but was unable to due to her mother’s poor health. Rita Kuhn died in 2022.

The Lewin Family

The constant presence of so many women — that was a real demonstration! They even closed the nearby Börse train station. But for some inexplicable reason, the women were not simply chased apart by force.

Erika Lewin

In Berlin, the Lewin family was very much a part of German society. Gerson became a member of the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish faith. His sons volunteered for the German Army during the First World War. In 1917, Gerson, Rosalin, and their five older children — who all held American citizenship — renounced their citizenship and became naturalized German citizens.

Josef Lewin, the fourth son of Gerson and Rosalin, married Else Krüger, a Protestant woman from Oranienburg, in 1922. The intermarried couple had four daughters. Josef worked as a stage worker at the Unter den Linden opera house until the rise of the Nazis. He was fired in 1933 for being Jewish and was unable to find steady employment, occasionally working smaller jobs. Else soon became the sole breadwinner for their family, often working from morning until night. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws were promulgated, immediately placing pressure on Else to leave her husband and children. When officials asked her to divorce Josef, Else replied: “I have four children with my husband, and I will not leave him. Race is bullshit!”

Josef applied to the American consulate in an attempt to regain his previously renounced American citizenship. However, with his oath to the German flag during the First World War in 1916, his request to revalidate his U.S. citizenship was denied.

Rosalin Lewin died of natural causes in 1938 at the age of 77. One by one, the members of the large Lewin family were targeted by the Nazis. Mathilde Lewin and her husband reported to the transit camp on Levetzowstraße. From there, they were deported to the Trawniki concentration camp in Poland and murdered in March 1942. Emilie Lewin was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp and perished there in May 1942. Gerson Lewin was deported to Theresienstadt camp in September 1942 and perished there at the age of 85. Julie Lewin and her husband were murdered in Riga, Latvia, in December 1942. Max Lewin and his two sons were deported to Auschwitz and murdered in 1943.

Josef Lewin’s daughter Erika, who was held in the Rosenstrasse building, recalled what took place there as follows: “The desperation was as great as the fear that the SS would shoot us. […] We were taken to the community hall on Rosenstrasse. […] 50 women and girls in a large, empty room on the second floor, where we lay in several rows on the floor, huddled next to each other, only our coats as a base. There was a bucket for the urine. One bucket for 50 people and the windows were locked! We neither saw nor heard what was happening in or in front of the house. Only once did I receive a signal from outside. A steward asked me for the house key. Otherwise, my mother wouldn’t be able to get into the house. That was, of course, a trick of hers. That way, she could be certain that I was indeed here. […] The constant presence of so many women — that was a real demonstration! They even closed the nearby Börse train station. But for some inexplicable reason, the women were not simply chased apart by force.”

After her release, Erika remained a forced labor worker. She later hid in another town until the end of the war. Josef Lewin passed away from a terminal illness in July of 1945, just two months after the defeat of Nazi Germany.