Inspirador

How Berlin Is Calling on Its Citizens to Water Trees

The summers are getting drier and drier, as well as the other seasons, that do not bring the amount of rain Germany is used to. Berlin's trees are struggling. How can a digital platform and an active neighbourhood offer a solution?

By Jonaya de Castro and Laura Sobral

The Inspirador is rethinking sustainable cities in identifying and sharing inspiring initiatives and policies from more than 32 cities around the world. The research is systemising these cases in categories, these are signified by hashtags.

#democratize_space

The availability of quality public spaces, combined with affordable housing and access to essential city services for all residents is a central aspect of a good quality of urban life. Public spaces support climate equaliy, environmental awarenesss, health benefits and energize the local economy. Cities that understand that having a home is a basic right to steps to democratize access to housing inspiring other cities around the world.

When you bike around Berlin, you can see that it’s one of the greenest cities in Europe. There are over half a million trees there – and some of the old ones have even survived the Second World War.

Sadly, the climate crisis is jeopardizing this. “If you live in Berlin you might have noticed that the last two years were really dry. We suffered through a drought,” says Julia Zimmermann, the manager of CityLAB Berlin, an innovation lab that works with data to solve urban problems. In the last year, the city lost 20% of its trees as a result of the increase in temperature and the reduction of humidity and rainfall.

Tree Maintenance is a Huge Logistical Burden for the City

The municipality of Berlin estimates that it costs € 2,000 to plant and maintain a tree in the first two years, during which they need 50 litres of water per day. That’s why the innovation lab has created the project Gieß den Kiez, a digital platform that allows citizens to get to know the tree species in each neighbourhood and commit to watering them. The project was created using the open data already available in the government platforms in order to prioritize and optimize the watering routes, propelling a new kind of collaboration between the authorities and the community.The CityLAB Berlin is an experimental lab for the city of the future that mixes a digital workshop, a coworking space and event space. Representatives of the government, civil society, academia and start-ups collaboratively develop new ideas to guarantee and enhance the livability of Berlin. "We are a small but agile team working together, sharing our ideas quite collaboratively," Julia assures. The Lab is funded and managed by Technologiestiftung Berlin, which is maintained by the Senate, and considers digitalization an opportunity to rethink existing processes, dismantle social barriers and create new forms of civic participation. The idea of Gieß den Kiez emerged quite organically once the CityLAB realized how much data on the city’s trees was already available: The Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland (BUND) had already mapped over half a million of them on their website. “So we thought ‘Hey, why not include something that adds value to this data?’”

The CityLAB team then decided to develop a platform that combined the data with other attributes, such as the amount of rainfall or water that is needed by each individual species. The goal was to offer valuable information to the communities that were already mobilized to water the city’s trees. The app was created by the team using open software such as Open Street Maps and open data from governmental sources.

The New York City Street Tree Map project served as inspiration for the creation of Gieß den Kiez. It allows users to click on a tree and calculate the costs or savings it generates for the city and its effect on CO2 consumption.

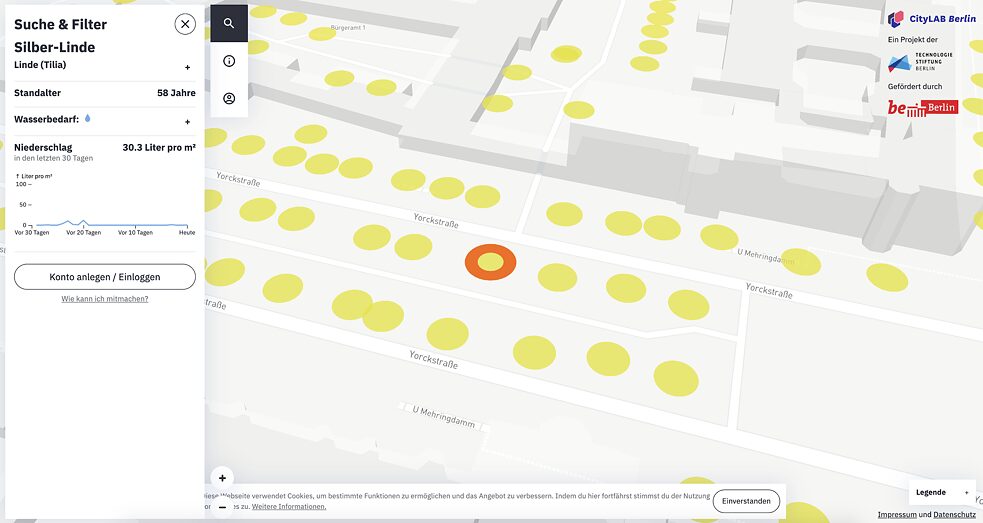

The Gieß den Kiez platform offers a map that allows people to explore over 627,000 trees. It shows the amount of water each of them needs depending on their age and maintenance profile. Users can indicate when they last watered a tree and subscribe to specific trees that they want to water regularly. The tool also shows how much rainwater a tree has received in the last 30 days. This data is drawn from the German Weather Service and updated daily. The map therefore allows the community, as well as the municipality, to see which trees need their attention.

In the app you can visualize how much water a specific tree needs.

| © Screenshot CityLab

In the app you can visualize how much water a specific tree needs.

| © Screenshot CityLab

People Were Ready to Collaborate

At the moment, over 1,000 citizen-caretakers are registered and over 7,000 trees are being cared for. Julia recalls that in the beginning of the project she was only interested in the aspect of open data. But, as the work progressed, what proved to be really important for the project was the people. She highlights how interested and engaged people are with this issue and believes that the citizens of Berlin develop a strong emotional connection to the trees in the neighbourhoods where they grew up. "They feel like it’s their own tree, even though it’s not their tree in the sense of private assets."We should never underestimate the relationship people have with the city they live in and how engaged they want to be in its processes.

Julia Zimmermann

My advice to someone who wants to do something similar is to prepare for heaps of community feedback.

Julia Zimmermann

Already Inspiring Other Cities

As the app is totally based on open data, adaptation should not be that challenging. The city of Leipzig reached out to the CityLAB and, because everything is open-source, they were able to replicate the entire code.Gieß den Kiez is a connection tool that combines open data in a map, neighbourhood engagement and the need for tree maintenance. But it is more than just a bridge that connects the trees that need water and the people who want to take care of their city by watering them: in the end, it connects people and democratizes space.

What Is This Series About?

The “Inspirador for Possible Cities” project is a collaborative creation by Laura Sobral and Jonaya de Castro aiming to identify experiences among initiatives, academic content, and public policies that work towards more sustainable, cooperative cities. If we assume that our lifestyle gives rise to the factors behind the climate crisis, we have to admit our co-responsibility. Green planned cities with food autonomy and sanitation based on natural infrastructures can be a starting point for the construction of the new imaginary needed for a transition. The project presents public policies and group initiatives from many parts of the world that point to other possible ways of life, categorized into the following hashtags:

#redefine_development, #democratize_space,#(re)generate_resources, #intensify_collaboration,#political_imagination