Übersetzungsprozess von Irene und Franz Faber

How Irene and Franz Faber went about translating “A Girl Named Kiều” into a German lyrical adaptation, using the example of the prologue.

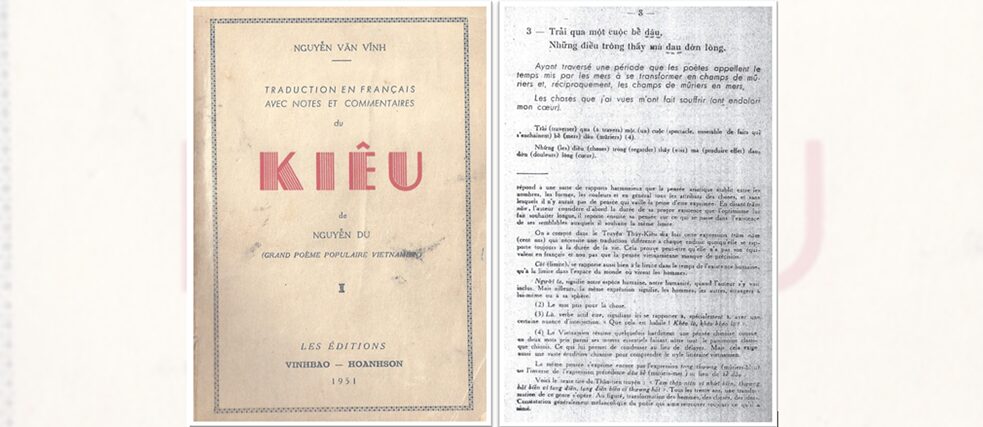

We know that the bilingual Vietnamese-French KIÊU edition by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh (Les Éditions VINHBAO - HOANHSON, 1951), gifted personally to Franz Faber by President Ho Chi Minh during Faber’s first stay in Vietnam from late 1954 to early 1955, was Irene and Franz Faber’s most important source-language text as they wrote their German adaptation “Das Mädchen Kiều.”.

Page 8 from this book, shown above, shows its basic structure: The first, uppermost part contains the text excerpts from the original, in this case the two verses “Trải qua một cuộc bể dâu - Những điều trông thấy mà đau đớn long” (v. 3 - 4.) The second part contains the corresponding (italicized) French translations. The third part is a word-for-word translation from Vietnamese into French. And finally, the fourth, and usually also longest section consists of French-language footnotes and comments on the above translations. Thus, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh’s work fulfils a double function: It is a Vietnamese-language primary text as well as a foreign-language reference text and quasi-reference work. We know that the Fabers also consulted additional secondary sources and that Irene Faber learned Vietnamese specifically to be able to translate from the original text wherever possible. Nonetheless, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh’s work is of decisive importance as it facilitated linguistic and intercultural understanding, especially for Irene Faber, who did the lion’s share of the enormous amount of philological research work that went into the seven-and-a-half-year project.

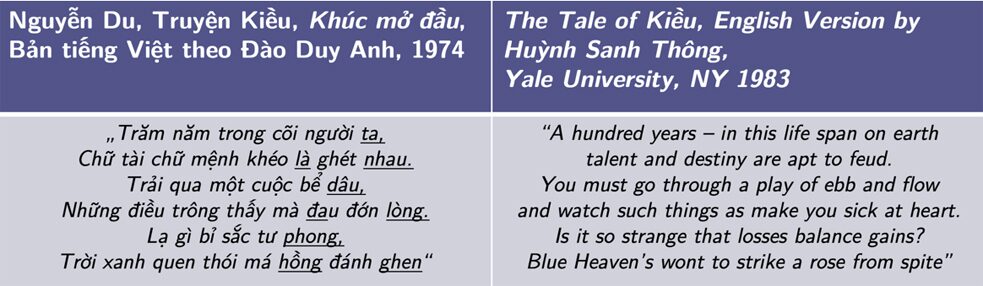

Let us now turn to the text excerpt I will use to illustrate Irene and Franz Faber’s translation process and methods. It is the first six lines of verse, or prologue of the work. The next figure shows the original Vietnamese text version according to Đào Duy Anh in the left column, and the English version by Huỳnh Sanh Thông on the right.

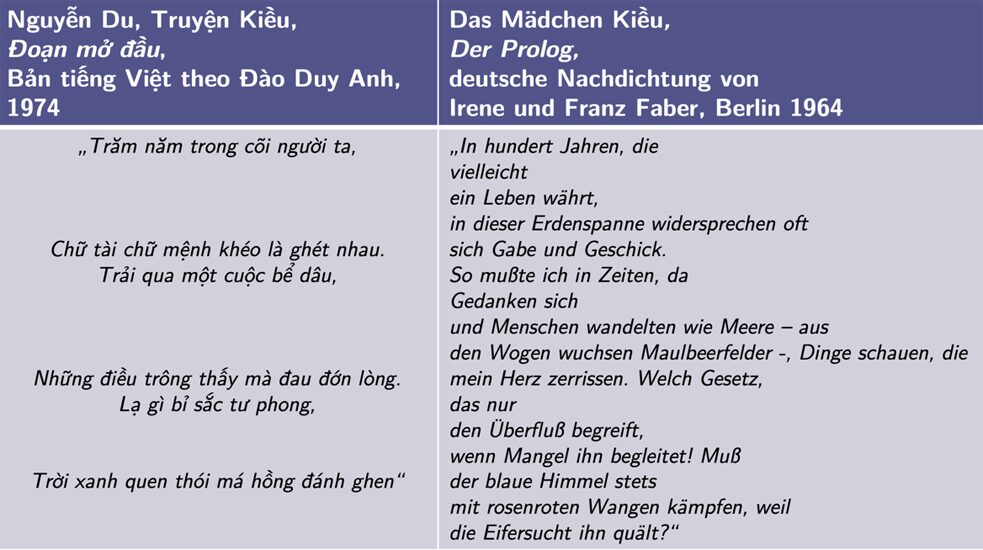

What is the first thing we notice? Both the Vietnamese and the English version each consist of six lines. Let me start off by pointing out that Huỳnh Sanh Thông’s English version – which, by the way, is considered the most influential lyrical adaptation of “Truyện Kiều” in the English-speaking world – is basically a linear translation that retains the original number of lines. Having noted this, let’s now turn to Irene and Franz Faber’s German translation.

By contrast, the German text consists of 16 lines, almost three times as long as the original. This ratio applies to the entire adaptation: The 3,254 verse lines of the original yielded a whopping 9,384 lines of verse in the German version!

Another formal difference: The German version is entirely written in iambic meter – a verse meter of Greek origin that consists of a short (unaccented) syllable followed by another (accented) syllable. In this case, there is neither a fixed number of accents nor a (fixed) rhyme scheme. The original Vietnamese version is written in a meter called lục-bát, which dates back to the 15th century. It is the meter of nursery songs, folk songs, but also of the “Truyện Nôm”, the verse novel or epic poem, and thus the most originary and important meter of classical Vietnamese poetry. Lục-bát is the Sino-Vietnamese expression for ‘6-8’, which means that the lục-bát meter consists of a (theoretically unlimited) alternating sequence of lines of 6 and 8 syllables or words. In terms of rhyme scheme, the 6th syllable of the first six-syllable line of the verse rhymes with the 6th syllable of the second eight-syllable line; the 8th syllable of the second line of the verse rhymes with the 6th syllable of the third[KT1] line of the verse, and so on. So there is a regular alternation between end rhyme and internal rhyme. The internal rhyme is very characteristic of the literatures of Southeast Asia. It is not nearly as widely used in China or India, which is what allowed the phenomenon of the epic poem to emerge as an independent literary genre of Southeast Asia in the first place.

The German version, written in iambic meter, does not keep the alternating 6-8-rhythm of the original, as is already apparent from the visual form of the text, instead breaking it down into different free rhythms. It also virtually miniaturizes ideas that are originally interwoven in one uniform structure into individual word groups and even down to individual words. Thus, in our text excerpt, the 1st line of verse of the original, “Trăm năm trong cõi ngưòi ta” is “accommodated” in four lines of verse in the German adaptation, that is:

“In a hundred years, which

might

span one lifetime

in this earthly space...”

The 2nd line of the original “Chữ tài chữ mệnh khéo là ghét nhau” corresponds partly to the 4th line and partly to the 5th line of the adaptation:

“... often at odds are

gift and skill.”

The third Vietnamese-language line of verse, “Trải qua một cuộc bể dâu” is also rendered in four lines of German verse:

“So I was compelled, in times when

thoughts

and people changed like the tide – from

the waves grew mulberry fields...”

Similarly, the 4th line “Những điều trông thấy mà đau đớn long” is rendered partially in the 9th, partly in the 10th line of the German rendition:

“... to see things

that tore my heart apart...”

From the above examples, we can see that the shorter 6-syllable lines yield even more lines of German verse than the longer 8-syllable lines: While the first 6-syllable Vietnamese line is rendered in four German lines of verse, it takes “only” two German lines to render the second 8-syllable line of the Vietnamese original. However, this is not only a formal-quantitative difference, but also involves a significant shift in contents and semantics. Vietnamese literary scholar Phan Ngọc stipulates that in the lục-bát meter, the 6-syllable line of verse must have a basic introductory character and lead the reader into a certain context [Example: “Trăm năm trong cõi người ta” = “In a hundred years, which / might/ span one lifetime / in this earthen space”. ], and that only the following 8-syllable line can convey the actual message [“Chữ tài chữ mệnh khéo là ghét nhau” = “often at odds are / gift and skill”]. It is not difficult to see that here, too, the translator substantially reworked the semantic architecture of the original and transferred it into the linguistical and metric context of the target language.

Aware of the complex and incommensurable structure of the original, Irene and Franz Faber wrote in their foreword: “Translating the work into an Indo-European language is fraught with difficulties which, at first sight, seem almost insurmountable. It is impossible to render the musicality of the Vietnamese language in German [...] Any translation of it – however faithful it may be – is therefore never more than a text without a musical score.” Does the text of the German adaptation “Das Mädchen Kiều” really lack a ‘score’? This is where Irene and Franz Faber were really hiding their light under a bushel. I claim that the above-described method of their German adaptation really reveals and does justice to the fundamental lyrical-subjective tenor in Nguyễn Du’s work, which is otherwise hard to discern, even for native speakers, because of the seemingly repetitive 6-8 rhythm and the numerous historical parables (điển cố) and classical metaphors (ẩn dụ) that are used in the original.

Let’s leave my claim for the time being and turn to another set of problems – the historical parables (điển cố). In our text sample, we can take a closer look at the parable “bể dâu” from the third Vietnamese verse line “Trải qua một cuộc bể dâu”. “Bể dâu” literally translates as “mulberry sea” or “sea of mulberries” and is a Vietnamization of the Sino-Vietnamese term “tang hải”, or “thương hải biến vi tang điền” [in English: “Where once there was the blue sea, mulberry fields grow today”, which represents the vicissitudes of life and transience of being]. It is a historical parable from the ancient Chinese book “Shen hsien chuan” [“Thần tiên truyện”, in English, “History of Gods and Immortals”], which in the late 18th century would have been part of Nguyễn Du’s educational canon in Vietnam. Today, however, it is far outside the canon of common literary knowledge. Irene and Franz Faber certainly had Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh and his scholarly footwork to thank for enabling them to unlock the deeper meaning of this historical parable or classical metaphor (see also the corresponding notes in the first illustration). Let us now compare how translators of the German and English versions approached this task.

Huỳnh Sanh Thông, the poet who wrote the English version, replaces the historical parable “bể dâu”/ “mulberry sea” with the metaphor of “ebb and flow”, a common image in the Indo-European language area. Irene and Franz Faber, on the other hand, attempted to translate the historical parable and integrate it into the German text lyrically and descriptively:

“So I was compelled, in times when

thoughts

and people changed like the tide - from

the waves grew mulberry fields...”

By the way, this method is systemically applied throughout the entire German rendition and a major reason why it is almost three times as long as the original, as I already mentioned. It is a matter of debate whether this explanatory-integrative method is capable of delivering authenticity or whether it actually constricts the poetically ambiguous language of the original, or even suffocates its almost magical-religious aura. On the other hand, stylistic peculiarities such as the historical parables are an integral part of a classical poetic work such as “Truyện Kiều” and it would certainly be a loss if they were entirely dropped in the adaptation.

But let’s return to the image of “ebb and flow” that was used in the English text. This metaphor certainly also expresses the idea of the erratic nature of human existence. But the picture of “flow” alone – “flout” in Old High German, “plo” in Indo-Germanic – denotes a rather general sense of movement and even of dynamics, of a vast oceanic expanse... By contrast, the image of the blue sea, from which mulberry fields now grow, implies a feeling of sadness, of existential loss, of the undoing of something that was once great, wide, in infinite motion... This thought, which is referenced in the prologue as the irreconcilability between talent and fate, between gift and skill, will pervade the entire epic poem as a fundamental existential feeling. It is, for example, the fear that any experience might turn out to be a mere illusion in an instant, a fear which the protagonist later experiences at the very pinnacle moment of her journey, in the scene where she vows her love to her friend Kim Trọng:

„Nàng rằng khoảng vắng đêm trường

Vì hoa nên phải đánh đường tìm hoa

Bây giờ rõ mặt đôi ta

Biết đâu rồi nữa chẳng là chiêm bao“

German:

“Through empty spaces and

late through the night

traveled,

for the sake of the flowers, once again

this path to...

be close to the one I love.

Now we stand

face to face in real life - but

who knows,

whether later this won’t just

be a dream

that lives in our memory” (p. 52)

Now that we have addressed the example of the historical parable and different ways of handling it in foreign-language adaptations, let’s now turn to the problem of classical metaphors. According to the literary scholar Trần Đình Sử, 240 verses, that is 7.2% of a total of 3,254 verses in Truyện Kiều, reference classical metaphors. In the prologue, it is mainly the metaphors “trời xanh” (“blue heaven”) and “má hồng” (“rosy cheeks”, “a rose”). In this context, both Faber and Huỳnh Sanh Thông literally translate the image “blue heaven” into the respective target language:

German version:

“... must

the blue heaven always

battle with rosy cheeks because

it is tortured by jealousy?”

The “blue heaven” is, of course, the demiurge, creator of the world. In the context of East Asian cosmology, however, there is no notion of a personal creator, so the image of “the blue heaven” is a genuine metaphor for the East Asian idea of an eternal, impersonal world order, which in this context is relentlessly pursuing “the rosy cheeks” – a metaphor for women, or at least for the most beautiful among them.

Also interesting here is the different ways to convey the image “má hồng”. The German version literally translates it as “rosy-red cheeks”; in the original, “trời xanh” and “má hồng” form a so-called parallelism (tiểu đối), i.e. a parallel and antithetic arrangement of words and word groups – a frequently used stylistic device in Truyện Kiều (862 of 3,254 verses, i.e. 27%, in 12 different variations). The German version retains this characteristic to some extent. By contrast, the English version renders the image “má hồng” as “rose” (for “women”), which is probably also a stronger metaphor in the Indo-European language area (as, for example, in Goethe’s famous poem “Heidenröslein”).

Without making any judgement, we can conclude that the English version – while retaining the formal sentence structure of the original – tends to replace historical parables and classical metaphors from the Vietnamese or East Asian artistic tradition with metaphorical images of Western origin. The German version, on the other hand, radically transforms the sentence and rhythmic structure, but makes an effort to largely integrate the traditional artistic language into the German text in a lyrical and descriptive way.

A final remark on the text excerpt we discussed. It is about the role of the lyrical “I”, or first-person narrator. Let’s read the following passage again:

“So I was compelled, in times when

thoughts

and people changed like the tide – from

the waves grew mulberry fields – to see things

that tore my heart apart...”

The original text features neither the pronoun “I” nor the possessive pronoun “my”. Already with regard to Tang poetry, for example Du Fu, literary studies speak of “self-oblivion”, which, however, does not necessarily have a negative connotation. In the prologue of “Truyện Kiều”, for example, the absence of a logical “I” subject is often interpreted as an important means to help the reader identify with the narration.

In the German adaptation – as well as in the English version – the use of the pronoun “I” introduces a distinct first-person narrator. This is only partly owed to German or English sentence structure, which requires at least one logical subject. Beyond the purely formal-linguistic requirements of the target language system, the act of literary translation is also heavily impacted by the entirety of aesthetic strategies and intertextualities in the literary tradition of the target language. In this case, the speaker’s perspective (“So I was compelled, in times when thoughts … see things

that tore my heart apart...”) departs starkly from the self-oblivion in the Vietnamese original and is instead rather reminiscent of verses from the tradition of classical German literature, such as the following quotes from Goethe’s “Dedication” from the tragedy “Faust”:

„Versuch’ ich wohl, euch diesmal festzuhalten?

Fühl ich mein Herz noch jenem Wahn geneigt?“

(Shall I attempt to hold you this time? Is my heart still willing to suffer that illusion?)

or:

„Mein Busen fühlt sich jugendlich erschüttert“ etc.

(My bosom feels shaken like that of a youth)

More evidence of the impact of the target language’s literary traditions on the adaptation can be found in the passage at the end of Kiều’s 15-year ordeal, after her suicide on the Tiền Đường River and before her rescue by the Buddhist nun Giác Duyên. In the German rendition, the first-person narrator, or lyrical self says:

“At all times, graciously

the heavens turned

to the victims of this earth,

...who even in hours of deep agony...”

This verse is less reminiscent of the original [“Mấy người hiếu nghĩa xưa nay - Trời làm cho đến lâu ngày càng thương”], but rather of these verses:

„Neige, neige

Du Ohnegleiche“

(Incline, incline,

you unequaled one)

or

„Ach neige,

Du Schmerzensreiche,

Dein Antlitz gnädig meiner Not“

(Incline,

you who are full of pain,

mercifully your face to my misery)

This is Gretchen’s prayer before the Mater dolorosa from “Faust Part I”.

This quasi-Goethesian narrative perspective does not spoil the essential spirit of the Vietnamese national epic. On the contrary, the first-person narrator in the Chinese chapter- and scene-novel from the Ming Period (if one may use the term in this context) appears as a pure chronicler or prompter of moral cues. The first-person narrator in the verse novels, especially in Truyện Kiều – even if there is no formal logical “I” subject – assumes the function of a lyrical “I”, emotionally engaging the reader. Seen in this light, the adaptation is able to unlock the poetic resources of the original, which only become real in the encounter with another language. And strictly speaking, an adaptation belongs neither to the literature of the source language alone, nor to the literature of the target language. It is an entirely new creation. It is world literature in the truest sense of the word.

Berlin-Biesdorf, 01 June 2020