It's only been a few years from the origins of graffiti in New York's underground on freight trains worldwide. We asked New York's Katherine Lorimer aka Luna Park about the history and unique position of art on freight trains in street art.

Katherine Lorimer: Graffiti as we understand it today – large, elaborate, stylized letter forms embellished with characters – was developed by inner-city youth and illegally applied with spray paint on the exterior of NYC subway cars starting in the 1970s. The burgeoning scene of graffiti writers recognized subway cars to be an ideal surface to carry their artwork and messages across the city. As the movement grew in popularity and the insides of subway cars were also increasingly tagged, public sentiment turned against the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). In the public eye, the graffitied subway had become synonymous with a crime-ridden and lawless city. Starting in the mid 1980s, the MTA implemented a strict policy of removing graffiti-covered trains from service and tightened security in its yards and layups. By 1989, the MTA declared victory over graffiti.

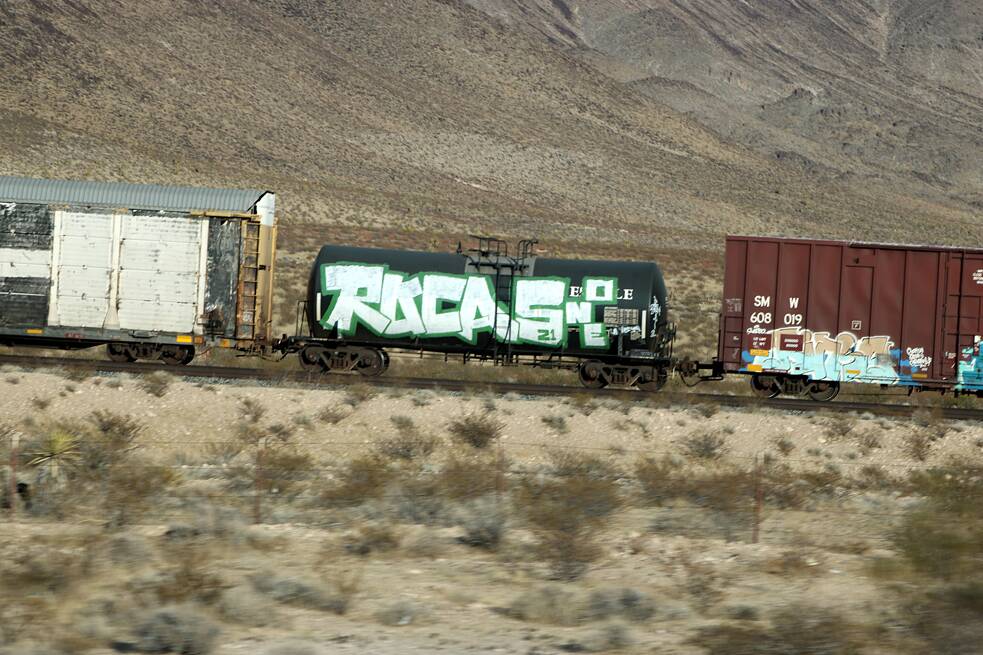

As subway trains became unavailable to paint, writers not only took graffiti to the streets, but also looked to other "rolling stock". While subway writers initially looked down on freights, they eventually became a viable alternative to the subway, with different types of freight cars (boxcars, tankers, hoppers, gondolas, and autoracks to name a few) making for interesting surfaces to paint. Early freight pioneers in NYC were writers such as TRACY168 and PNUT; in Philadelphia, SUROC and BRAZE led the way.

As more and more writers realized their artwork could be transported far and wide on freights, a subculture centered on freight graffiti started to emerge. With millions of freight cars on the rails, there is a seemingly endless supply of canvases on which to paint. As freight trains often travel across borders, freight graffiti can be seen in Mexico and Canada as well as in the United States.

What are monikers? And how do they differ from other artworks on trains?

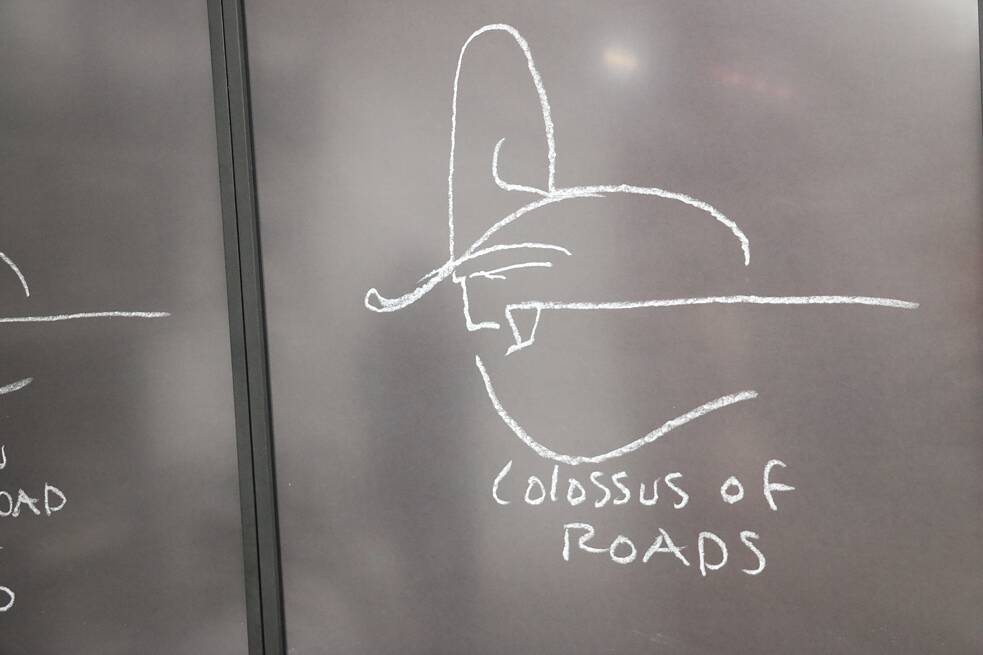

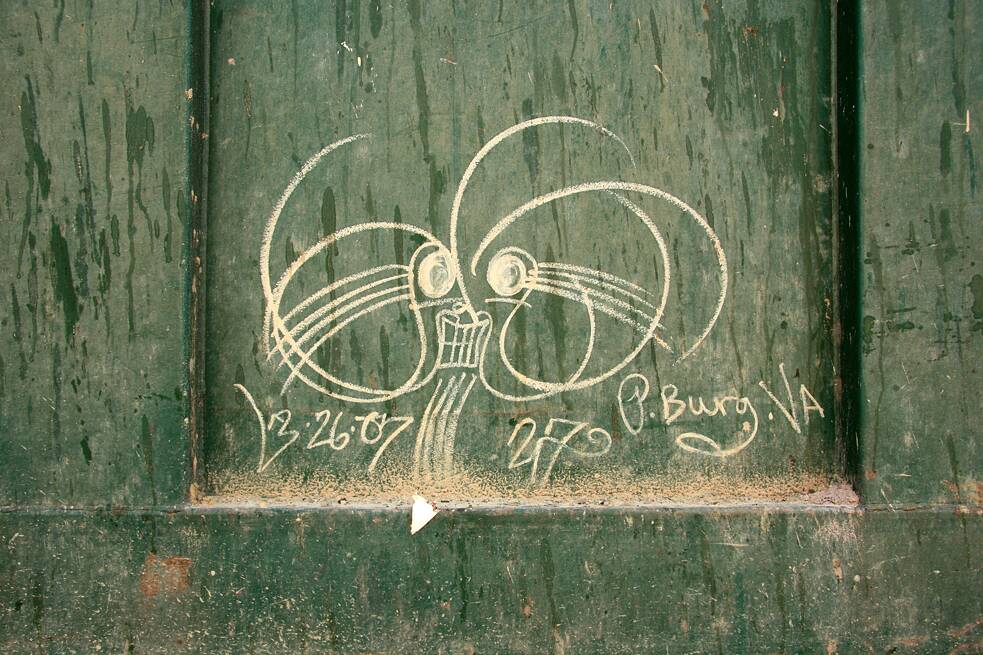

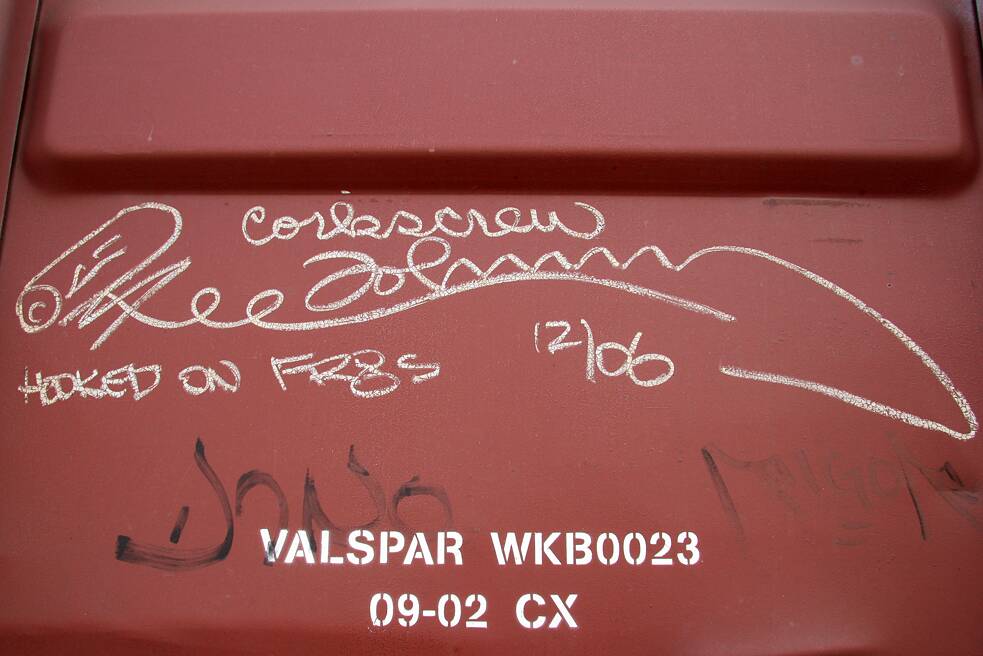

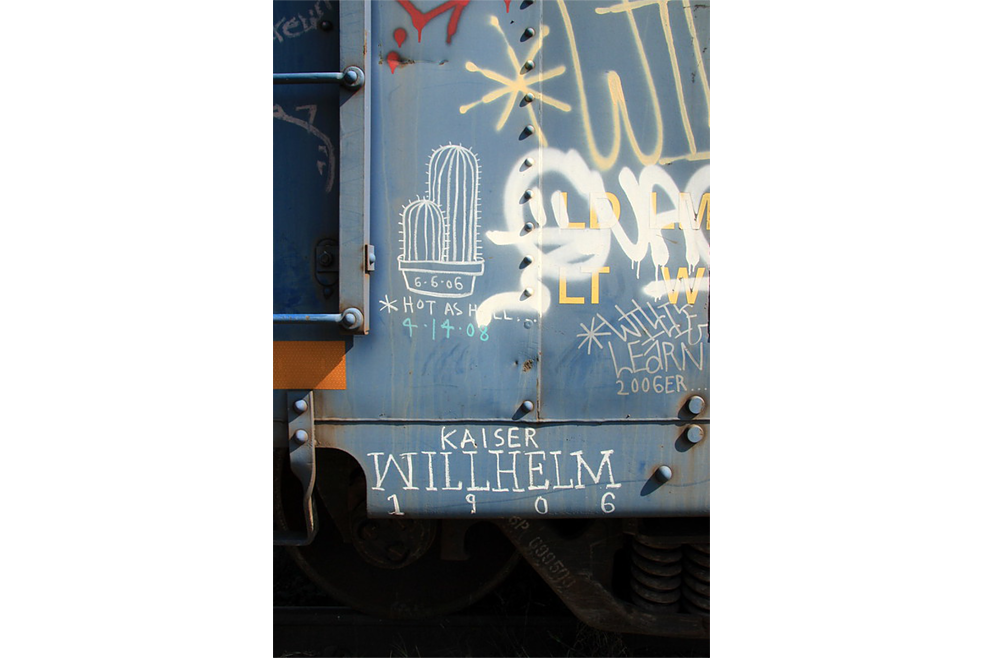

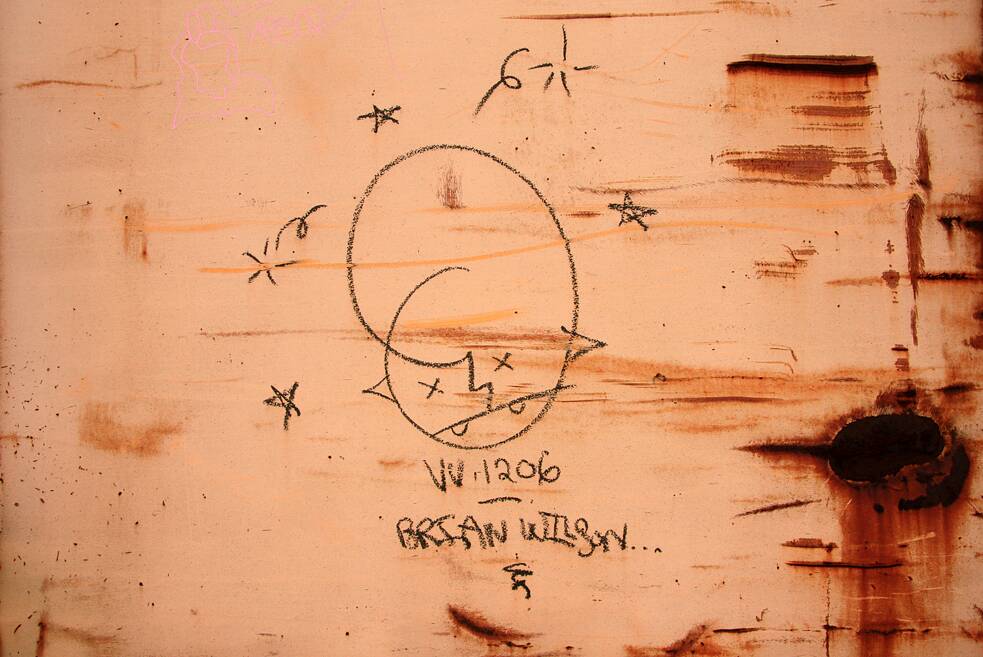

Monikers, also known as hobo or boxcar art, are a form of writing on freight trains that predates the contemporary graffiti that evolved out of the subway era. Typically written in chalk or oil bar, monikers were first employed by railway workers and hobos “riding the rails” at the dawn of the 20th century. Trainhoppers scrawled a so-called “hobo code” – coded signs, symbols or pictograms – onto freight trains, trees, fence posts, bridges and other rail adjacent infrastructure to convey messages and warnings about particular places. Contemporary graffiti writers and the anarchopunks who continue to hop freights today embraced the historic moniker subculture and brought it into the 21st century. Alongside the larger, more colorful graffiti productions found on freight cars, one often sees a smattering of smaller, symbol-based monikers and tags

Unlike graffiti on walls, the vast majority of freight graffiti is not seen by the public. Freight lines skirt the edge of town, often passing through industrial areas. The United States being such a car-centered culture, many people simply aren't aware of their local rail infrastructure.

This certainly is not the case with rail fans – and the super rail fans known as "foamers" – who know all the "benching" spots. Benching is a term for photographing graffiti on trains that carried over from the subway era. Writers would meet within the subway system – the most famous writer's bench being at 149th Street Grand Concourse in the Bronx – and wait to see and photograph the latest painted trains.

While freight yards in urban areas are typically fenced off, making access challenging, in more rural areas, the trains are more easily accessible. It is inherently risky to paint and bench freight trains, especially in active yards, where railway workers connect individual cars that weigh hundreds to thousands of tons each. Most freight rail operators employ so-called "bulls" as security to police their freight yards and apprehend trespassers. Between millions of freight cars and millions of miles of freight rail lines – never mind competing freight line operators - it would be impossible to legalize the freight graffiti movement.

Is the scene of artists around art on trains different from the normal graffiti scene or are there overlaps?

There are certainly graffiti writers who have specialized in painting freight trains, but there is also an overlap into the larger graffiti scene. Ease of accessibility to freight trains varies nationwide. In more remote locations, freight graffiti might be the only graffiti in town, so to speak. So it really boils down to a matter of opportunity: given access, time, and paint, most graffiti writers will find it hard to resist the lure of painting steel.

Freight Terminology

freight = goods and products transported on the railways

writers = preferred term to describe what became known as graffiti artists

benching = the act of photographing graffiti on trains

rolling stock = broad term to describe all types of railway vehicles

foamers = rail super fans

monikers = hand-drawn symbols and tags on trains dating back to the early 20th century

trainhopper = person who illegally boards and rides freight trains

bulls = railyard security