What does Rotwelsch actually mean? How long has this particular vocabulary existed? Who speaks it and why? Klaus Siewert enlightens us. He looks back to the time of Martin Luther and draws a line to contemporary literature.

Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible into German is regarded as a pioneer of supra-regional understanding in Germany and as the basis for the “New High German” written language, our modern “High German”, which developed in the German lands over the next few centuries. In his translation, Luther sought to find a form of language that would be understood by as many people as possible – as an alternative to the various translations into the different dialects of the Franks, Thuringians, Bavarians, Alemanni, Swabians and Saxons into which the German language area was fragmented. A Saxon could not understand a Bavarian, or only with difficulty, any more than a Swabian could understand his Thuringian compatriot in the east of the German-speaking area. But be careful: just because you couldn’t understand a dialect then or now doesn’t make it a secret language.Luther’s passion

Tired of struggling to find the right words for his Bible translations, exegesis and religious-political discourses, Luther pursued his special interests: his curiosity centred on the Rotwelsch language, which had developed as a supra-regional secret language in the 12th/13th century on the basis of Middle High German and Middle Low German dialects. In 1528 he published Von der falschen Betler Büberey. This is mainly concerned with different types and techniques of begging and is based on the Liber Vagatorum, the book of wandering beggars, published in 1510. The work is accompanied by a Rotwelsch-Germanic dictionary with 219 entries, one of the oldest documentations of the Rotwelsch language and an attempt to decipher it.Exchange between the disadvantaged

It is the language of the so-called “fifth estate”, the vagrants, outlaws and socially disadvantaged of the time. It was passed on for centuries, forming the basis of the later “Rotwelsch” dialects, and is still spoken today in isolated instances by tradesmen on the street. The intended function of a secret language is achieved by the creation of new words from mother tongue lexemes and morphemes, as well as by neo-semantisation, i.e. deliberately induced changes in the meaning of words:- rotboß = beggar’s hostel

- wintfang = coat

- kleckstein = traitor

- bschiderich = bailiff

- zwicker = executioner

- iltis = town servant

“Rotwellsche Grammatik” (Rotwelsch Grammar) from 1755 | ed. Siewert, 2019

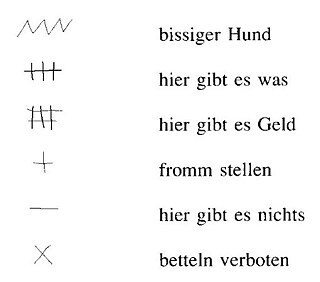

Signs on the wall

Over the centuries, the old Rotwelsch and the later “Rotwelsch dialects” were accompanied by non-linguistic secret messages, the so-called “Zinken”; these were signs attached to houses and forks in the road that informed and warned as an expression of the solidarity of the community of vagrants and travellers – and were also popular with crooks:

“Zinken” (from top to bottom: biting dog; here’s something; here’s money; pious behaviour; here’s nothing; begging forbidden) | Windolph, 1998, p. 19

Part of literature

After the idyllisation of vagrancy associated with the ideals of freedom in the Romantic period, via the provocative social criticism of Hans Fallada’s Blechnapf (Who Once Eats Out of the Tin Bowl / The World Outside), secret and special language also appears in contemporary German literature beyond Christiane F.’s Bahnhof Zoo (Zoo Station) as a constitutive literary element in ever new guises and functions.Word! The Language Column

Our column “Word!” appears every two weeks. It is dedicated to language – as a cultural and social phenomenon. How does language develop, what attitude do authors have towards “their” language, how does language shape a society? – Changing columnists – people with a professional or other connection to language – follow their personal topics for six consecutive issues.

October 2024