Today, Klaus Siewert invites us to join him on a journey to the Hamburg of yesteryear. On this journey back in time, we learn the nocturnal jargon of Hamburg’s docklands. And we learn how the kettle-beaters in the dockyards conversed – despite the infernal noise they made.

The German language has never existed. From the very beginning, there was a coexistence of different languages, and this is still the case today. We still recognise the dialects that evolved from the various West Germanic tribal dialects. For about 500 years we have used the standard language, also known as High German, as an instrument of supra-regional communication, flanked by other varieties such as technical languages, regional colloquial languages and, finally, special and secret languages. On closer inspection, this patchwork turns out to be much more fragmented here and there. In Hamburg alone, our fieldwork revealed more than ten different secret and specialist languages.Field research in the red light district

On the way to one of the most famous districts in the world: when the sun goes down in Hamburg’s St. Pauli district, the night jargon, the secret language of the district, comes to life. Until the 1980s, it was spoken by pimps, pub owners, bouncers and entertainers, and understood by the prostitutes.At some point, the night jargon fell silent and I set out to do fieldwork in St Pauli to preserve the language that was threatened with oblivion.

Excerpts from an interview with Stefan Hentschel, a famous red-light promoter and pimp in St. Pauli: ballermann for “pistol”, bring me the Eisen (iron), ballermann, bambule looking for a fight, da wurde Zoff gemacht (there was trouble), bellutschika (fight) – I’m not a gambler, dude! Should we still do the letter “C”? Giddap, Dottore! ... cappis, for Captagon “stimulant”, laß mal cappies rüberwachsen (lit. let cappies grow over, i.e. hand over cappies). – Then: casmus … what? cesmus “lesbian woman who has taken over the male role”.

A day later, we’re at the letter L, and Hentschel ironically explains the nocturnal jargon: loreleysuppe (Loreley soup), that’s a “bad broth”, probably like a bouillon cube with hot water, and behind it is the beginning of Heinrich Heine’s Lorelei poem: “I do not know the reason why / To sorrow I’m inclined”; hühnerstrip (chicken strip) – any suitor would think hühnerstrip has something to do with striptease in St. Pauli, but that’s not the word, but this is a “chicken grill”.

Interview with Stefan Hentschel, St Pauli, Annenstraße | Siewert, Nachtjargon, 2003, 14

From the red-light district pub to the hotel bar

Nocturnal jargon – a hermetically sealed secret language of the old red-light district residents? Far from it! By the 1950s at the latest, this jargon had been picked up by the dance bands and transported to Hamburg’s posh hotels beyond the Reeperbahn. In my search for remnants of the night jargon, I met Volker Zaum, the former leader of the quartet “Die Playboys” (The Playboys). He knew of two songs with lyrics in nocturnal jargon that had never been published and were considered lost: “Achiele toff” (good food) and “Nachtjargon” (nocturnal jargon). In fact, we were able to discover an old tape recording and save the two unique Nachtjargon settings! According to Volker Zaum, the lyrics of the two songs were probably written in the 1950s or 1960s. They were the brainchild of a former red-light district pub owner whose name my source could no longer remember.schi lobi, keine reibe,

kein geschicker von schabau,

keine fleppen, keine Bleibe!

According to my informant’s recollection, these lyrics also existed in written form at that time, but: “I have not yet found the written lyrics”. The linguistic knowledge of dance musicians that still existed in the 1950s has largely been lost half a century later. Volker Zaum: “I hope you understand the lyrics better than I do, because I couldn’t put some of the words into context after such a long time.”

Communication against noise

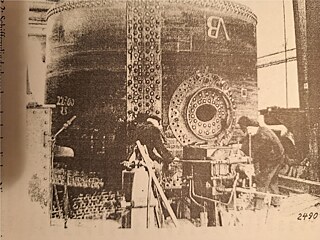

We are entering a different milieu: below St. Pauli, in the harbour, in the dockyards and on the jetties, the Kedelklopper (boiler knockers) were busy using pick hammers to knock the lime deposits off the boiler walls of the steamships. They invented a language to communicate over the noise of the boilers – by vocalising at the word boundaries.Esthi udi ali atwi eteni? This strange-sounding question is based on the Low German “Hest du al wat eten?”: “Have you eaten anything yet”? A 70-year-old contemporary witness on the Kedelklopper language explains: “The construction is very simple. You take all the consonants before the first vowel from each word or part of a word and put them after it, add an -i and that’s it!”

From its beginnings in the mid-19th century in the microcosm of steamship boiler rooms, where it was used for mutual communication, it later became a secret language and spread throughout the port area and the workers’ quarters. It was used as an instrument for internal agreements, especially during the labour disputes of the Weimar Republic, until it fell silent with the end of steam shipping in the mid-1930s.

Ship’s cylinder boiler at the riveting press, in the centre the manhole through which the Kedelkloppers entered the boiler. Ottenser Eisenwerke, circa 1930 | Siewert, Kedelkloppersprook, 2002, 21

Dann könnt ji uns all sehn, (Then you can already see us all,)

Dann goht wi henn no Blohm und Voß, (Then we go to Blohm and Voss, – a Hamburg shipyard)

Uns Geld dor to verdeen. (To earn our money there.)

Een Rundjer und blaue Bücks – (A lined jacket and blue trousers –)

De Mütz ganz kühn im Nacken, (The cap boldly on the neck,)

Getränk und Brot sind in de Tasch, (Drink and bread are in the bag,)

Een grote Tüt voll Swatten … (A big bag full of chewing tobacco ...)

Wi sünd Amborgerhi Etelki-Opperkli, / wi arbeit’t öbendri bi Ohmbli und Oßvi, / sünd üzfidelkri un ümmer opperpri, / kaut Attenswi un hebt ändlichschi Ostdi

(We are Hamburg kettle knockers / we also work at Blohm and Voss, / we’re jolly and always cheeky, / chew tobacco and are always thirsty)

Ini ethi extni episodeï (In the next episode), we return to Hamburg. Then our route takes us to an island in the River Elbe, where we explore the Schockfreier language.

Word! The Language Column

Our column “Word!” appears every two weeks. It is dedicated to language – as a cultural and social phenomenon. How does language develop, what attitude do authors have towards “their” language, how does language shape a society? – Changing columnists – people with a professional or other connection to language – follow their personal topics for six consecutive issues.

November 2024