Saudi Arabia is experiencing a newfound burst of colours. The kingdom that was long recognized for austere conservative social codes, is being increasingly acknowledged worldwide for a buzzing cultural and artistic scene which the government is actively promoting as it strides towards a plan to diversify its income away from oil.

The outcome is profound: from vibrant paintings coming to life on cafes’ walls and murals breathing life into sidewalks, to grand events like the ongoing Noor Festival lighting up the moderately-cool winter nights of Riyadh and filmmakers from far and near drawn to Jeddah’s film festival, a Saudi and international audience is being dazzled by a fresh taste of local art and a real feel of native talents.But amidst this artistic explosion and rapid transition, an unfolding struggle speaks of a dimension overlooked by spectators: artists are unable to balance between the full-time art creators they’d love to be and other jobs they’ve always had. The limited opportunities of government and private funding, in addition to the young art market of Saudi, means they’re unable to live off their art solely.

“Full-time artist? This I would love to be, but I don't think it can happen!” Abdulaziz Almojathil, a well-established calligrapher and designer, said. From his workshop in AlBaha, a city in southwest Saudi, the artist said that his canvases and top-quality paints need a budget of their own, and that despite his success in earning a “considerable income” from a clientele of companies and art collectors who purchase his artwork, he still needs his full-time job as an administrative manager.

Abdulaziz Almojathil, a well-established calligrapher and designer, has been able to make lucrative returns from selling his artwork to art collectors to companies, but says the cost of production still makes him dependent on his day job. | ©Ali Elghamdi

“There are unlimited possibilities when it comes to making sufficient profit from art, but that requires good marketing skills, connections, and the ability to master certain artistic skills” which need to be acquired and developed, he explained. This, he adds, requires full devotion, when his office job “is overwhelming and negatively affects his engagement with art” but is essential as a sustainable source of income.

Despite a surge in funding opportunities as well as options through which they could sell their artwork, painters say such opportunities are often not very rewarding, or are not necessarily suitable due to being tied to certain parts of the country.

Too much to juggle

Over the past decade, Saudi authorities have trimmed a once-tight hold of religious institutions on public space, which had in the past limited artists' freedoms to express themselves and showcase their work.Layla Alhamed, a Jeddah-based school principal by day, and book writer and painter by night, in addition to being a wife and mother of one, had worked hard to create herself a foothold in the rapidly expanding local art scene. Capturing her hometown’s nature and landscape in her paintings, and the overlooked stories of village women in her books, she managed to draw an appreciative audience to several exhibitions that featured her work over the years, installing some of her artwork in public spaces as part of several events, as well as conducted a number of workshops on painting and history of art.

Despite such accomplishments, she feels that nailing such opportunities comes at a hefty emotional and physical toll. In a rapidly developing art scene, Alhamed is unable to keep track of all the funding opportunities that are arising, and she acknowledges that the available funding and sponsorship opportunities she is aware of are extremely limited. “The amount and quality of paintings I produce is never going to be enough to support me financially,” she says, adding that “the physically and mentally consuming nature of my job only allows me very little time to focus on my art or look for platforms and new outlets''.

This in turn creates another layer of emotional and mental toll. “Art, for me, is more than a passion, it’s my way of expressing my identity and a catharsis. Not being able to do that due to my other commitments affects me mentally and emotionally,” she explains.

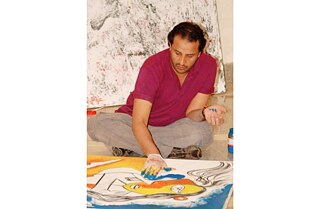

Even for those who manage to merge between their artwork and day jobs, like public school arts teacher Aref Alghamdi, time constraints imposed by their jobs means many lost opportunities. Alghamdi, a well-established painter who owns his art gallery in Riyadh and whose art was exhibited in Italy, France, and the US, he uses his art lessons with younger students to teach his style of abstract painting that merges cubism and surrealism with an obvious influence from Spain’s renowned Salvador Dali.

Aref Elghamdi, a well-established painter, says his day job of teaching art in public schools has been an inspiration and motivation for him, as he enjoys passing on his skills to students, and also learns from their additions. Used with permission. | ©Privat

“Talking to my students about art gives me a fresh perspective, allows me to teach my style, and keep grounded to art,” says the artist in calmly-spoken words. His grounded manners, however, could not conceal his deep love for art and the time he spends working on paintings. “Appealing to an art audience requires producing artwork with high specifications, which needs years of learning and training for the artist, and devotion,” he said, adding that being committed to schooling semesters, he misses a lot of opportunities to join national and international galleries and events.

Rough start

For those wanting to embark on a career in art, knowing where and how to begin is rarely easy. Ahmed AbdulSalam Jora, an engineering graduate in his mid twenties, discovered his love and passion for Arabic calligraphy while still a student. He has since been trying to equip himself with the knowledge and skills.But this is no easy quest. In between looking for permanent jobs to secure a living, and paying the little resources he has on workshops and online courses, Jora fears he won’t be able to keep this much longer. “I apply for funding and try to find ways to showcase my calligraphy works on various platforms, but at this rate, I may be forced to drop my pursuit if I land a permanent job, since the task of marketing is a tedious one that requires professional art agents to handle,” says the young artist in despair.

Budding calligrapher Ahmed Jora has been struggling to find opportunities to showcase his work in a rapidly-growing, yet competitive, art scene. | ©Ahmed Jora

Ahmad Almontashri, an assistant professor of arts who asked for his university job not to be used since it's his personal insight as an artist that he shares, argues that full-time jobs do not affect an artist’s talent which he describes as instinctively inherited, “it does, however, affect the skills,” he stated, adding that this is a major holdback for beginners like Jora, or experienced artists like himself. Almontashri concludes that at times, “combining academia and art have discouraged many from practicing art.”

This article is published in collaboration with Egab.

June 2024