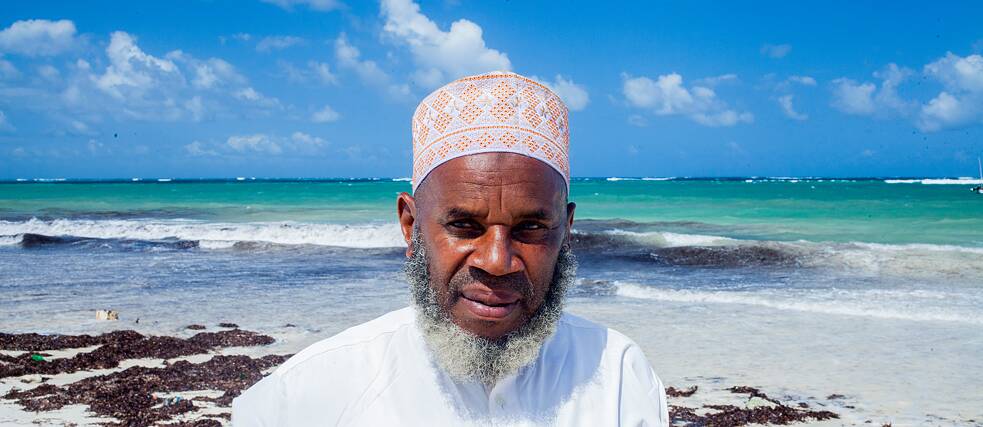

Shaame Kombo Hassan’s story is one of resilience, endurance and aspiration. Born in Utange, Mombasa he carries the legacy of his ancestors who migrated from Pemba in Zanzibar in search of a better life on the Kenyan coast of the Indian Ocean. He narrates his family’s journey – from harbour to harbour –, the struggles they faced and their undying hope for a better future.

My great-grandfather, Yussuf Shaame Kombo, made the fateful decision to leave Pemba towards the end of the 19th century. Known for its lush clove plantations and rich cultural tapestry, Pemba was not just a home—it was a world unto itself. But life on the island was becoming increasingly unstable, with political turmoil and economic hardship looming. The lure of new opportunities across the ocean in Mombasa beckoned, and my great-grandfather, filled with hope and fear in equal measure, set sail on a humble dhow, leaving behind everything he had ever known.I often try to imagine what that journey must have been like—the vastness of the Indian Ocean, the uncertainty of what lay ahead, and the weight of the decision to leave home. His bravery laid the foundation for our future, but it also marked the beginning of a long and painful struggle for acceptance and belonging. Forty years ago, at the age of 22 years, I decided to move further north along the Kenyan coast and settled as a fisherman in Mtondia in Kilifi, where many more people from Pemba were already living.

Pemba is the second largest island of the Zanzibar Archipelago. It’s located in Eastern Africa, off the coast of Tanzania in the Indian Ocean. From its port, the Mkoani Sea Port, ferries connect the Tanzanian mainland with the Archipelago’s largest island, Zanzibar. On the mainland, Tanzania has a northern border with Kenya. And in Kenya – embedded in the mainland yet surrounded by water – lies Mombasa, the country’s second largest city and the most important seaport in Eastern Africa. That’s where Shaame’s great-grandfather first arrived after leaving behind his homeland, Pemba Island. | Map: OpenStreetMap.org

The sea – an unforgiving master

Upon their arrival, my great-grandfather and his family settled in Utange on Mombasa Island, where they faced a harsh reality. Although the Kenyan coast was already a cultural melting pot, the new immigrants were seen as outsiders, forever regarded as strangers in a place they longed to call home. My great-grandfather and his family faced discrimination at every turn—economically marginalized and socially ostracized, they struggled to make ends meet.My father, Hassan Kombo, often told us of the hardships they faced. The humiliation of being looked down upon and the relentless struggle to eke out a living through fishing and small-scale trading. The sea, which had once been their livelihood, now seemed a harsh and unforgiving master. But despite these challenges, our forefathers persevered, their spirits unbroken, their hope undimmed.

Beneath the façade of gentle waves of the Indian Ocean lie many untold stories of the Pemba community living on the coast of the Indian Ocean in Kenya. | Image: Paul Munene

Our biggest challenge

The deepest wound inflicted on our community was the curse of statelessness. To be born, to grow and to live in a place and yet be denied the right to belong there is a pain that runs deep, a wound that never really heals. For not having proper documentation, we were denied the most basic rights—education, healthcare, employment opportunities—they were all out of reach for those of us who were seen as outsiders, despite having settled here long before Kenya attained political independence.I remember the frustration of being turned away when I tried to open a bank account, the humiliation of not being able to register a mobile phone SIM card, and the anger when my children were denied admission in the school in our neighbourhood. In the eyes of many, we do not belong here, even though this land is all we have ever known.

Shaame Kombo Hassan with his wife and daughter | Image: Paul Munene

Kenya’s independence and its consequences

My father told me that the reasons for the discrimination were mainly political. Before Kenya attained independence in 1963, there was significant debate and tension surrounding a ten-mile coastal strip along the Indian Ocean. This area had a unique historical and political context due to its connection to the Sultanate of Zanzibar and colonial agreements. The Arab and Swahili communities living along the East African coast feared that they would lose their political and cultural autonomy under a new independent Kenyan government.Supported by the Sultan of Zanzibar, they called for a ten-mile coastal strip to be either detached from the rest of Kenya or to remain under the sovereignty of Zanzibar. The post-independent state would have none of it and refused to recognize them as Kenyan citizens as a form of punishment.

Fishmongers buy their fish from the fishermen on the beach in Mtondia | Image: Paul Munene

Longing for the home port of Pemba

Our connection to Pemba remains strong. Pemba is not just a place in our history; it still reminds us of who we are. Every year, during Islamic holidays such as Eid, we make the pilgrimage back there—a journey that is as much about reconnecting with our roots as it is about keeping our culture alive.My father’s stories of Pemba were filled with nostalgia—the bustling markets, the aroma of spices in the air, and the soothing rhythm of the ocean waves. These memories are our lifeline, a way of passing on the essence of who we are to our children. Even as we focus on making a life for ourselves in Kenya, we hold on to these traditions and ensure that the spirit of Pemba lives on.

My children’s future

For many years we asked ourselves: Will we ever truly belong here? There is some light at the end of the tunnel, but the journey is far from over. The answer remains elusive, but the struggle for recognition, for identity, for a place to call our own, is a struggle I will continue as long as I live. Over the last few years, the Kenyan government has accepted that we are Kenyans and should be treated as such. However, before we can get official identification documents, we are subjected to an arduous screening process, unlike other Kenyans.I hope that one day our grandchildren will not have to suffer as much as we have suffered. Until then, I will keep telling our story, because it is through our stories that we keep the spirit of our ancestors alive. My message for others who might be in a similar situation is: Never let go of hope. We are more than the labels placed upon us, more than the struggles we face. We are the children of those who dared to dream of a better life, and it is our duty to live that dream, to fight for our place in the world, and to ensure that our stories are never forgotten.

Eliphas Nyamogo recorded the story. A big thank you goes to Shaame Kombo Hassan for sharing his harbour story and to Paul Munene for the pictures.

October 2024