The Bauhaus

Designing life

The Bauhaus art school aimed to promote social and as such affordable living through the artistic avant-garde. At the core of the movement was the idea that revolutionary design could bring about a new way of life for a society in the midst of an upheaval.

By Nadine Berghausen

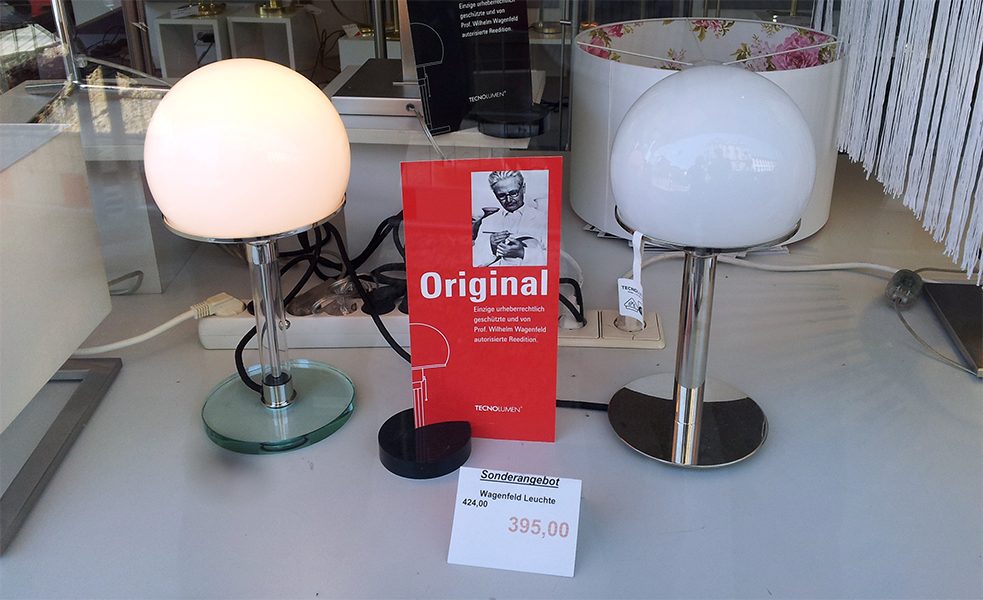

If you’re thinking of upgrading your living room with a Bauhaus classic, like a Marcel Breuer Cesca chair, or setting decorative accents with a Wagenfeld lamp, you’ll have to reach deep into your pockets to pay for one of these prized designer objects these days. Given the mantra followed by Bauhaus designers, who designed furniture with the less well-heeled in mind, the prices their work fetches today seem paradoxical. And the prevailing opinion of Bauhaus pieces has done an about-face in keeping with their market value. Nowadays, their simple elegance is more trendy than revolutionary. Yet back in 1919, the Bauhaus was established with a radical agenda to create a new creative framework that could completely modernise everyday life.

The Bauhaus art school was founded in a society suffering the devastating effects of the First World War and the industrialized economy. Inflation, hunger, unemployment, homelessness and social unrest fuelled the desire for a new social order. In this environment of political and social unrest, a group of artists came together around architect Walter Gropius, who would go on to found the Bauhaus art school in Weimar. Gropius felt direction from a creative designer was the solution to the dire social straights his country was mired in. "Building is the design of life processes," he said about architecture, and some critics accused him of succumbing to a romantic utopia.

Radical modernization of life

Unlike the British Arts and Crafts movement, which idealized the Middle Ages and reclaimed Gothic shapes, the Bauhaus focused on a new approach to design. Interdisciplinary groups of artists would work, initially with craftsmen in Wiener, then later with industrial machines in Dessau, to create objects that would then shape the culture of the future. In the Bauhaus Manifesto, Gropius wrote: "The ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building! […]Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to the crafts! […]The artist is an exalted craftsman."

If Bauhaus artists wanted to improve the living conditions for lower-income people in particular, then their work had to be affordable. It was important that objects could be inexpensively mass-produced, so the Bauhaus forged a new design aesthetic no one had ever tried before. Their return to the most basic geometric shapes, the humble square, circle and triangle, was unconventional, as was the limited colour palate using just the most basics: red, yellow, blue, black and white. Art critic Paul Westheim visited an architecture exhibition organized by Gropius, and was less than impressed: "Three days in Weimar and if I never see another square as long as I live, it will be too soon."

Art? Not at the Bauhaus!

Bauhaus proponents strictly adhered to its principles. Artistic aesthetics went against the ideology, so design took its cues from purpose and function, rather than style. This functionalist approach set the stage for inevitable conflict with those Bauhaus professors – known as “masters” in Bauhaus jargon – who came to Weimer and Dessau as visual artists.

This austere and innovative design language was particularly apparent in everyday objects. In the coffee and tea sets produced in the metal workshop, it is obvious that the individual elements did not have to fit together to satisfy the artistic standard. The cream pitcher, sugar bowl and pot are all quite different in style, and sometimes don’t look like they belong together, as their role determined their design and not the desire to create a set in the traditional sense. This tea infuser by Marianne Brandt is just one of example of how the movement turned its back on the applied arts. The “form follows function” motto was not new to the Bauhaus, but is inextricably linked to the Bauhaus style today.

Tea infuser MT 49 by Marianne Brandt, photographed by Bauhaus photographer Lucia Moholy in Dessau in 1924.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa

The new, modern approach was also visible in the textiles and fabrics that emerged from the Bauhaus. The textile workshop wove rugs with abstract shapes, very different from the narrative tapestries so popular at the beginning of the century. Otherwise it focused on everyday objects, like tablecloths, runners, children’s clothes and test strips for industry. These were primarily crafted by female Bauhaus students under the tutelage of Master Gunta Stölzl, once a student herself.

Tea infuser MT 49 by Marianne Brandt, photographed by Bauhaus photographer Lucia Moholy in Dessau in 1924.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa

The new, modern approach was also visible in the textiles and fabrics that emerged from the Bauhaus. The textile workshop wove rugs with abstract shapes, very different from the narrative tapestries so popular at the beginning of the century. Otherwise it focused on everyday objects, like tablecloths, runners, children’s clothes and test strips for industry. These were primarily crafted by female Bauhaus students under the tutelage of Master Gunta Stölzl, once a student herself.

A rug by Bauhaus artist Agnes Roghé

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Hendrik Schmidt

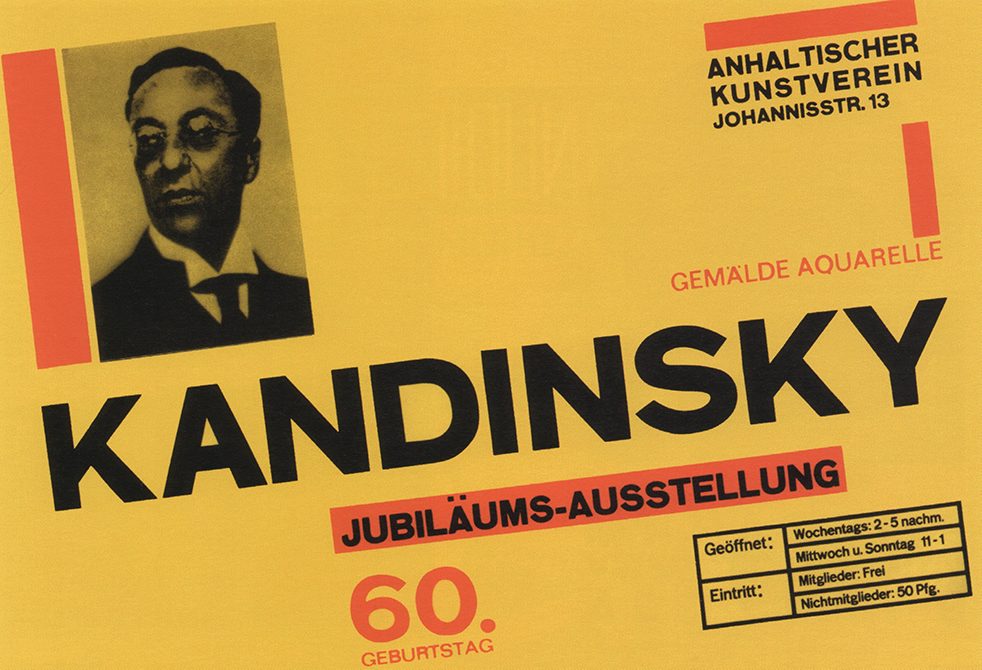

But Bauhaus innovation went much further than just a design revolution. New occupational fields emerged at the unique interface between technology and design developed in the Bauhaus workshops. Marketing took a front seat too, and photographers were trained and modern typographies - mainly in red and black – designed to promote the pieces. The concept of a graphic designer was born in courses like the "systematics of advertising" and the "awareness effect" held in the advertising workshop.

A rug by Bauhaus artist Agnes Roghé

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Hendrik Schmidt

But Bauhaus innovation went much further than just a design revolution. New occupational fields emerged at the unique interface between technology and design developed in the Bauhaus workshops. Marketing took a front seat too, and photographers were trained and modern typographies - mainly in red and black – designed to promote the pieces. The concept of a graphic designer was born in courses like the "systematics of advertising" and the "awareness effect" held in the advertising workshop.

Poster mock-up by Herbert Bayer in 1926

| Photo: © picture alliance/Heritage Images

Poster mock-up by Herbert Bayer in 1926

| Photo: © picture alliance/Heritage Images

Design for the masses

The revolutionary design developed at the Bauhaus under the leadership of Walter Gropius took a more social turn in 1927 under new director Hannes Meyer. Meyer argued that the Bauhaus must begin designing with a stronger focus on needs of the people - for the "proletariat". Under the new director's aegis, the motto shifted to "the people’s needs instead of the need for luxury!"; and the overriding question to be answered was: "What do people really need in their everyday lives?" Not more rugs, it seemed, so durable carpets were produced instead. The various workshops worked together to create materials with the tensile strength to withstand being stretched over a tubular steel chair frame.

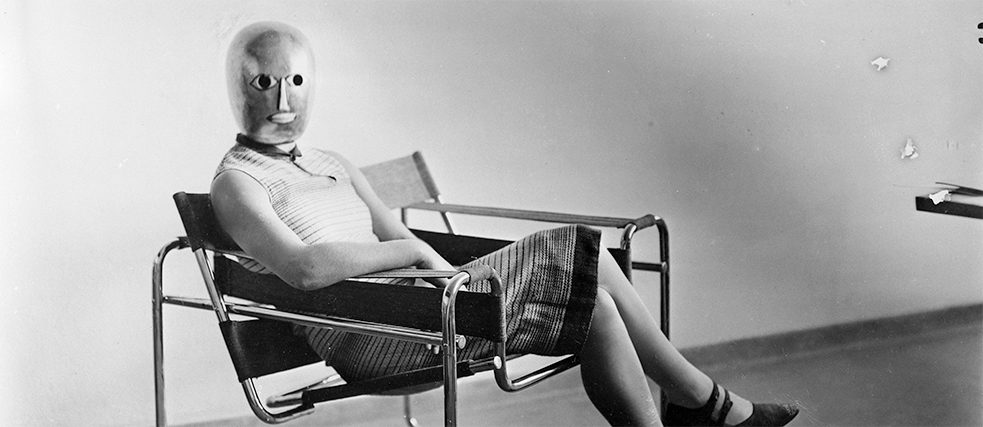

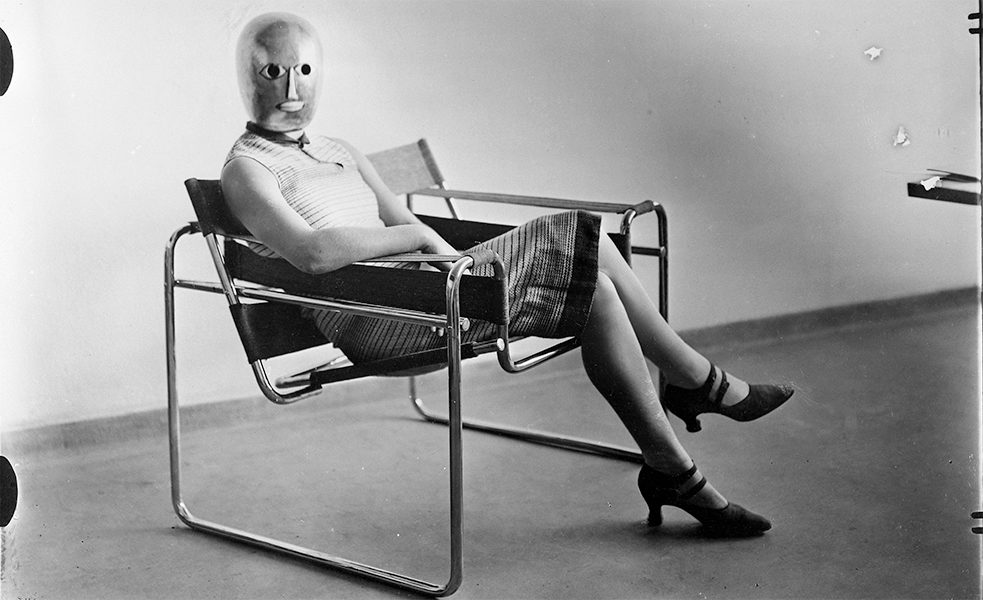

Woman sitting in Marcel Breuer tubular steel chair, 1926.

| Photo (detail): © Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin/Dr. Stephan Consemüller

The Wagenfeld lamp mentioned at the beginning is a good example of how wide the gap between the ideal of design for the masses and economic reality could be. Handcrafted out of silver and glass, it was a far cry from an inexpensive lamp the working class could easily afford. Even the famous desk lamp’s creator, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, soberly attested to this fact when he returned from a trade fair in 1924: "Dealers and manufacturers laughed at our products. Although they looked like cheap machine products, they were in fact expensive handicrafts. Their criticisms were justified."

Woman sitting in Marcel Breuer tubular steel chair, 1926.

| Photo (detail): © Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin/Dr. Stephan Consemüller

The Wagenfeld lamp mentioned at the beginning is a good example of how wide the gap between the ideal of design for the masses and economic reality could be. Handcrafted out of silver and glass, it was a far cry from an inexpensive lamp the working class could easily afford. Even the famous desk lamp’s creator, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, soberly attested to this fact when he returned from a trade fair in 1924: "Dealers and manufacturers laughed at our products. Although they looked like cheap machine products, they were in fact expensive handicrafts. Their criticisms were justified."

Today a popular and by no means inexpensive home-decoration piece: Wagenfeld lamps for sale.

| Photo (detail): © Christos Vittoratos CC-BY-SA-3.0

And reality turned out quite different anyway: These days, Bauhaus design has gone full-on mainstream and the luxury objects are valued more for their aesthetics than for their function. But the Bauhaus principles and ideals have gone down in history. They continue to shape contemporary design and architecture and are still taught at art and design colleges worldwide. The legacy of Walter Gropius and his successors Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is perhaps most clearly recognisable in many of our homes, as they were responsible for bringing progress, a modern lifestyle, and an understanding of clear forms into our living rooms today.

Today a popular and by no means inexpensive home-decoration piece: Wagenfeld lamps for sale.

| Photo (detail): © Christos Vittoratos CC-BY-SA-3.0

And reality turned out quite different anyway: These days, Bauhaus design has gone full-on mainstream and the luxury objects are valued more for their aesthetics than for their function. But the Bauhaus principles and ideals have gone down in history. They continue to shape contemporary design and architecture and are still taught at art and design colleges worldwide. The legacy of Walter Gropius and his successors Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is perhaps most clearly recognisable in many of our homes, as they were responsible for bringing progress, a modern lifestyle, and an understanding of clear forms into our living rooms today.