Classical, Contemporary and Early Music 2023

All change for classical music

In 2023 it seemed that many German ensembles seized the opportunity opened up by the classical crisis. New orchestras, new payment models, new experiments with virtual music. From the Bayreuther Festspiele to MaerzMusik: there have rarely been as many new beginnings as we are seeing right now.

By Axel Brüggemann

It’s rare for the foundations of classical music to be rocked as much as they have been this year. Local theatres and orchestras are competing for audiences and appropriately qualified staff. Even Parsifal with future Bayreuth director Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson was performed to an auditorium in Hanover that was just about half full. Theatres from Cologne to Halle, from Kiel to Freiburg – and even time-honoured opera institutions like Dresden’s Semperoper complain of a significant reduction in audience numbers.

Reacting creatively to shrinking audiences

Classical music in Germany is currently a subject of discussion as well. After WDR’s director general, Tom Buhrow, kicked off a huge debate about whether ARD could still afford a budget for 16 radio orchestras, choirs and big bands with more than 2000 employees, drastic financial cuts were announced this year at music rival ARD. Orchestras, theatres and festivals are under pressure to justify their existence and are searching for creative answers in a complex transformation process.The director general of the Bavarian State Opera, Serge Dorny, has observed for instance that his auditorium is no longer filling up from “front to back” – i.e. expensive seats selling before cheap ones, but instead from “back to front” – if at all. Dorny is publicly questioning the pricing structure of German theatres, wondering whether classical music is still accessible to all, and he is calling for more movement, especially where theatres and orchestras are state-funded. “We need to be much more flexible at local level,” he said in his podcast, Alles klar, Klassik?, “it isn’t right that every theatre in Germany has to operate according to the same principle as repertory theatres. We must adapt better to the needs of individual situations, we should consider stagione systems [an organisational form of theatre that presents a limited number of performances, mostly of new material], or exclusive companies starring celebrity actors, or completely different concepts.”

Classical music’s arena for public debate is becoming smaller and smaller too: Bayerischer Rundfunk (Bavaria’s TV and radio broadcaster) has just stopped broadcasting KlickKlack, the last show on German TV dedicated solely to classical music (arte has not been recording new episodes of Rolando Villazón’s up-and-coming talent show Stars von morgen for a while now). There are also discussions regarding the possibility of merging the culture listings of regional ARD broadcasters in Germany to form a single evening schedule. The situation appears even more dramatic for printed media: at the end of 2023 the classical music magazine Fono-Forum will be discontinued in its current form – a new publisher is set to take over the long-standing paper, which in its day came up with the award “Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik”, and publication will resume from February. The magazine missed out on cornering the digital market. Die Deutsche Bühne, a magazine published by the Deutscher Bühnenverein, will have just six issues per year in future instead of 12.

One thing’s certain: the music scene in Germany needs to reevaluate itself. And that’s exactly what it has done in 2023. Orchestras like the Gewandhaus in Leipzig or the Thüringer Bachwochen festival have experimented successfully with new payment models: “Pay as you want” or “Pay as you can”, where the audience decide on their own admission prices, were well received, as was a monthly flat rate at Stadttheater Hagen (with this model you pay a monthly charge of nine euros and that allows you to attend all performances). There are plans to continue the pioneering project in 2024 as well. Theater Bremen even offered a “No Pay November” deal – free admission to every show for apprentices.

AI still in its infancy on the music scene

Germany’s classical crisis seems to have inspired a new creativity, in terms of both structure and content. They are ramping up the search for ways to incorporate innovative technology such as artificial intelligence (AI), as well as for new virtual spaces. One high-profile pioneer of AI in the field of music is Ali Nikrang, who became Professor at the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich earlier this year. Nikrang is certain that artificial intelligence will change the music scene forever. “For a long time we thought that music could be a trailblazer where AI is concerned,” he said recently in a classical podcast, “but we’ve come to realise that it’s much easier to generate words and pictures with artificial intelligence.” Nevertheless, Nikrang is convinced that computer-generated sounds and composition tools are up to standard for everyday use already. Admittedly it’s still difficult to imitate symphonies on a large scale, he explains, something that was illustrated by the rather poor AI composition of Beethoven’s 10th symphony in Bonn. At the moment, he reckons, artificial intelligence is primarily still a technical tool used by composers to support their creative decision process.Experiments with augmented reality

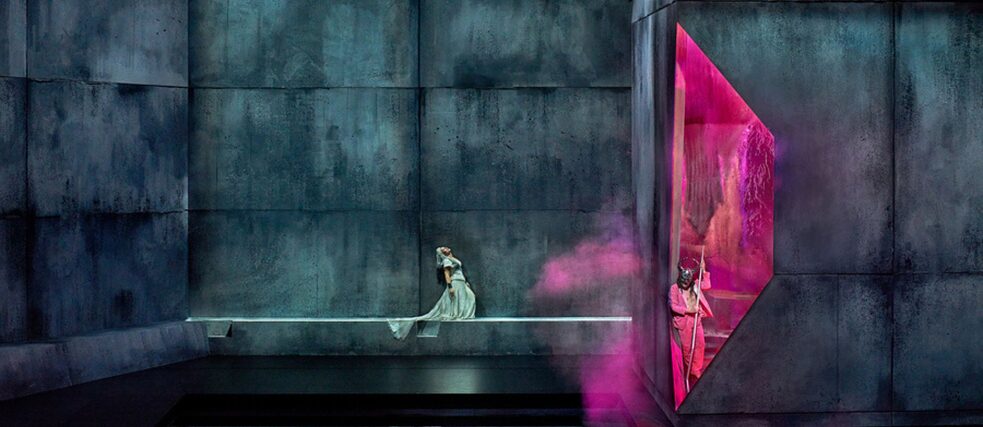

Classical music has already become immersed deeper in virtual spaces than it has in the realm of artificial intelligence. In this capacity, Stadttheater Augsburg has played a pioneering role. Alongside opera, drama and children’s theatre, they have developed their own digital division. Augmented reality is integrated seamlessly into the opera productions, meaning that audience members can experience Orpheus’ hellish journey into the Underworld with real flames thanks to special glasses. “The developments in technology also facilitate a new level of involvement in theatre,” explained Tina Lorenz, head of the Digital Division at Theater Augsburg, in a recent classical podcast. In Augsburg, you can order a virtual reality headset for delivery to your home by cycle courier, which allows you to experience an authentic Stadttheater production with a view of the stage and genuine theatre acoustics from the comfort of your sofa.The first experiments with AR this summer at the Bayreuther Festspiele followed a somewhat bumpier road. Director Jay Scheib dramatised his production of Parsifal in a way that turned Wagner’s opera into a multimedia experiment: virtual rocks, trees and ravines transformed the stage set of the Festspielhaus theatre, while flowers, decorations and holy spears winged their way through the animated theatre as if guided by magic. The only catch: because of the high cost there were only AR headsets for select audience members, and they had to be willing to pay extra for the privilege too. Everyone else experienced a conventional opera performance. As can be seen from both Augsburg and the Bayreuther Festspiele, classical music is absolutely ready to create new openings beyond the stone temples that characterised music in the 19th century – the virtual world has become the stage reality of the 21st century.

Incredibly little has been said about AI at contemporary music concerts this year. Indeed many people seem to think that new music in particular is becoming old hat. Critical voices asked whether the composers at the Donaueschingen Musiktage festival had all been tasked with writing the same piece, because the works ended up being so homogeneous. In fact this was the first time there had been a motto in Donaueschingen – specifically Collaboration – and under the artistic direction of Lydia Rilling 70 per cent of the 23 world premieres were written by women this time. Efforts to involve performers in the creative responsibility were noticeable everywhere. For instance Matana Roberts and Clara Iannotta gave their singers text fragments to hold instead of sheet music, in order to ensure that the hierarchies were as flat as possible within the creative process. The highlight was the play Was wird hier eigentlich gespielt? (What’s actually being played here?) by Iris ter Schiphorst and Felicitas Hoppe, partly because in this performance the meaning of the word has been completely deconstructed. At one point the lyrics say: “Wer jetzt nicht singt, verklingt” (Sing out or fade out). A sentence that’s probably representative of the entire new music scene.

The ECLAT Festival in Stuttgart seemed more dynamic. Director Christine Fischer was able to recruit participants from 30 different countries, who delivered a diverse picture of the modern music scene. The MaerzMusik festival in Berlin presented a similar variety with its new director Kamila Metwaly. The opening musical performance Hide to show by German composer Michael Beil was a mixture of instrumental and electronic sounds, video and audio clips on loop, and incorporated film, video, theatre and installation elements. And at the end there was even – unusually for new music – something to make the audience chuckle, for instance when constant redundancies ironise the ubiquitous visibility of things, yet at the same time their invisibility, through high-volume information on the internet.

New orchestras with new ideas

Nevertheless there is still the question of where modernity is heading. The former GMD of Theater Bremen, Yoel Gamzou, thinks that modern classical needs to come down from its ivory tower. At the Beethovenfest in Bonn he presented his new orchestra one.Music. An ensemble that attributes equal value to new music and the great classics (such as Beethoven’s 5th Symphony). And the orchestra’s debut concert, featuring a variety of works by Robin Haigh, Florian Kovacic and Andrew Creeggan did indeed demonstrate the aesthetic diversity of current music whilst at the same time delighting the audience.Composer Moritz Eggert chose a completely new path when he wrote Kairosis, the first interactive video game opera. You are cast as a young composer, whose rehearsals of her new work keep being interrupted. Players have to make a succession of active decisions as to how the situation develops. Music logically becomes part of the plot here. Kairosis is available to play online free of charge.

Another 2023 trend could be observed at the Beethovenfest in Bonn: the obvious efforts of many orchestras and theatres to get close to their audiences and encourage participation. Beethovenfest director Steven Walter set new standards in this respect. Over the past two years he has transformed the festival from a sedate classical event into an innovative platform that appeals to a young audience as well: cycling tours with classical music, concerts in empty swimming pools, involvement of local amateur ensembles, or interactive programmes where the audience gets to make decisions – these are just a few of the successful experiments by what’s probably Germany’s newest and most exciting classical festival at the moment.

A performative approach to the orchestral leaders

Proximity to the audience seems to be a key theme for many concert halls at the moment, including and even particularly relating to the choice of conductor. Simon Rattle was musical director of the Berlin Philharmonic for many years, after which he returned to his native England, and he is now in his first season as the new principal conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO). As well as classics, there’s a good portion of closeness to people on the agenda here as well. Rattle likes to be seen in public with FC Bayern München players, sometimes dresses up in a Lederhose for Oktoberfest, and is passionate about conducting Bavarian oompah bands. More than 100 wind ensembles from all over Bavaria had applied to play with him at the Symphonischer Hoagascht (a sociable evening in a pub). Rattle also defines the plan for a new philharmonic hall in Munich as a symbol of proximity to the audience. After Bavaria’s Minister-President Markus Söder had initially ordered a “pause for thought” on the building project, it has now been incorporated into the coalition agreement of the new Bavarian state government.The Konzerthausorchester in Berlin is prioritising audience proximity with new chief conductor Joana Mallwitz. Mallwitz is omnipresent in the capital and the advertising campaign is personally tailored to her, radically so. That doesn’t just ensure approval. Especially after the somewhat mediocre conducting at her debut concert with Gustav Mahler’s First Symphony, the question on everyone’s lips in Berlin is whether the musical director is able to live up to her own marketing promises in the long term.

The personality of musicians seems to be particularly important in Berlin at the moment. This is partly because the classical scene had just been reorganised. After the resignation of Daniel Barenboim, the Staatskapelle Berlin (and consequently the Staatsoper Unter den Linden as well) selected Christian Thielemann as his successor. The gifted Wagner and Strauss conductor is well-known for a rather conservative approach to programme planning, which makes him a polar opposite to the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. Kirill Petrenko has spent years working persistently on perfecting the sound, and this season he has once again put together a concert schedule that cleverly juggles established and new repertoire items to challenge the audience and orchestra in equal measure, whilst defining classical music as a voyage of discovery. The orchestra hasn’t been as good as it is under Petrenko for a long time.

The new order of the Berlin classical scene

That just leaves the capital’s largest opera house: both the intendant, Dietmar Schwarz, and general music director Donald Runnicles will be leaving Deutsche Oper Berlin in 2026. The big question is – who will the new artistic director Aviel Cahn appoint as musical director? Oper Frankfurt has demonstrated this season how refreshing a clever young musical director can be: Thomas Guggeis is popular with the audience, and Frankfurt has already been voted “Opera house of the year” for the seventh time. They’ve opted for a director duo from artistic backgrounds in Hamburg this year too: artistic director Tobias Kratzer and conductor Omer Meir Wellber are set to lead the Staatsoper on the Elbe into the future, and together they certainly represent an unconventional leadership approach.While classical music has already been struggling for some years in other countries, the crisis of institutions is now arriving in Germany too. And this comes at a time when many of the buildings are in need of renovation. Many theatres and concert halls were built or refurbished after the war, and are due for general redevelopment in the next few years. Some of the cities like Cologne, Stuttgart, Frankfurt or Dresden are looking at building costs of a million euros. It won’t be easy to convince the municipal authorities to stump up investments on that scale. And yet just as the German music scene is undergoing such change, it demonstrates its creative aptitude for trying new approaches. Shows us all that it belongs to a society in transformation. Rarely has there been so much movement in music, so many new departures, so much innovation and so many experiments as we are seeing right now.