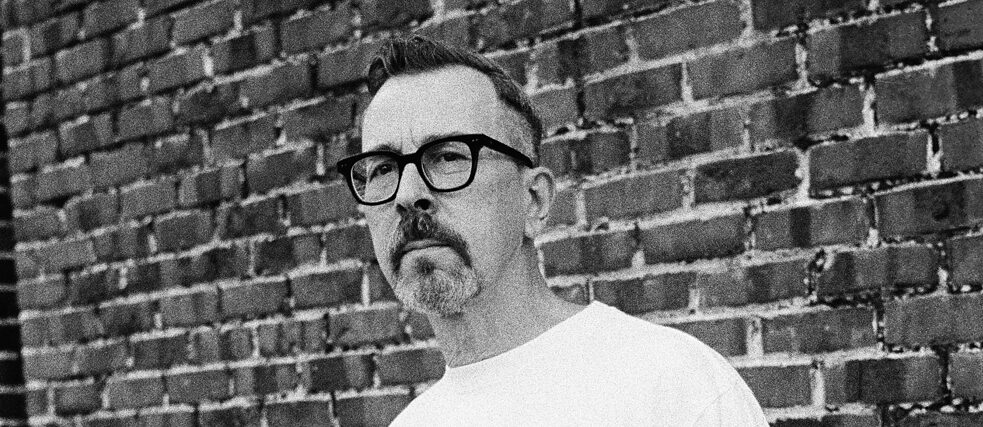

Hans Nieswandt

“I don’t want to be in the spotlight”

As a DJ, author, journalist and musician, Cologne-based Hans Nieswandt has a special position within the German house and techno world. In our interview, he not only discusses the changing times, but also the regional peculiarities throughout the German scene.

By Hans Nieswandt

Can you still remember your first run in with techno?

Hans Nieswandt: For me, techno always means house and techno. I lived in Hamburg at the end of the 80s. Hamburg was early in terms of the whole development of electronic music. As early as 1987, there was a club night called Shag. It was once a week at the Caesar’s Palace club on the Reeperbahn. That’s where I heard acid house for the first time. Acid house was a revelation for me and a huge game changer, because disco or dance music was feeling stagnant for me at that time. You had Prince, Michael Jackson and Kool and the Gang, but the really exciting time of the early eighties, post-punk, was over. People knew every song and would even dance to them. That stopped with acid house. There were no familiar tracks. Instead people danced to basic elements, so to speak: beats, baselines, 303 chirps. You danced into the unknown, into the future. What I like about acid house to this day – and what distinguishes acid house from techno – is that I found it to be neutral. It wasn't coloured by mood, in the sense of being aggressive, dark or evil, but was rather just neutral, simply pulsating, driving and trippy.

every week was a revolution

You were already working as an editor at that time and then went to Cologne in 1990 to write for the music magazine Spex. How did you end up DJing?I was already DJing in the early 80s. At the start, when acid house took off, I hadn’t yet mixed, but I did play records in small venues on the Reeperbahn from time to time. Soul, disco, garage house and everything you can imagine. In Hamburg there was no urgency for techno because there were incredibly good clubs. As far as techno was concerned, I was more of a dancer. But when I went to Cologne, there was nothing going on. So I developed my own club or DJ pursuits and put on events and club nights. In addition, especially in ’89, ’90, ’91, every week was a revolution in terms of music. There were all these labels like NuGroove and Strictly Rhythm, but also Warp. It was also not yet the case that only one type of music was playing in the clubs, but you’d have reggae, hip hop, house and techno all playing on the same night. It was all built up dramaturgically. I practiced mixing at home with enormous enthusiasm in order to showcase this. Actually, you shouldn’t do this, but I also practiced in public some of the time (laughs). There were also a lot of underground events, for example in cleared out auto body shops. We’d set it up with a sound system, a fog machine and a stroboscope – and the party was ready to go. I played a lot of techno and house there too.

What did you see in terms of the development of techno in Cologne during those years?

Because I was not only a DJ, but also a journalist, and because the reputation of our parties spread to other cities relatively quickly, I naturally got around a lot. At the beginning of the 90s, techno suddenly became a big thing everywhere, a huge experience that everyone wanted to participate in. That's pretty much worn off today, I think. Especially in the first half of the 90s, I thought it was great how German federalism manifested itself, so to speak. All the cities – Berlin, Frankfurt, Cologne, Munich, Hamburg, and a little later Dresden, Leipzig, etc. – had their own sound. I don’t think much of nationalism, but I like the idea of regionalism, that certain things are developed in an area that are typical of it.

In Cologne it was Bauhaus techno

And that’s changed today?It doesn’t work that way anymore because nothing has time to develop undisturbed, because every new idea has already gone around the world in an afternoon. That has its advantages and disadvantages. But because there was no internet or smartphones back then, a kind of sound aesthetic was able to develop in Cologne, for example, that was very different from Berlin. Berlin was hard, industrial bunker techno – end-times techno, dancing on the volcano. In Cologne it was Bauhaus techno, clean lines, minimal design, design in general. In Frankfurt, bucolic party techno was in – “Gude Laune” techno. In Munich, decadent fashion techno was the thing, but I don’t mean that negatively at all. It differentiated itself like that a bit everywhere. Visiting each other and experiencing these different styles was very interesting for me.

Where do you see techno today?

What I really liked about the whole techno and DJ culture was the orientation of the dancers. I was tired of standing in front of stages and watching bands – everyone looking in the same direction. That’s also something I find really regrettable about today’s DJ culture, where it's kind of gone in an idiotic direction. When I became a DJ, you could only see DJs in clubs – and DJs in the club were in the corner. The show was the people and the music. Now it’s the case that kids are endlessly seeing DJs on YouTube, how they’re being idolized, standing on stage in the middle of pyrotechnics and who knows what. I saw Jeff Mills play Tresor at his first gig in Germany. Your jaw really drops when you see what he does with just his hands. That’s real magic. He still comes from the school of “hidden in the dark corner". That’s where he makes his magic. Today, everything’s done on its own. There’s no risk at all anymore. Nothing can go wrong. The most difficult thing today is the choice of music. But to the same extent that it’s become easier and easier, so to speak, it’s moved more and more into the camera lens. That’s why there are all these sad videos where you see them clutching onto buttons, pretending to do some kind of activity, or performing by kind of dancing around. It’s all so stupid, actually. I also liked that being a DJ was and is a great thing for introverted freaks. A New York clubber once explained that to me: there are “crazy freaks”" and there are “cool freaks”. I’m more of a “cool freak”. I don’t want to be in the spotlight. I want to pull the strings and make the puppets dance, but I don’t want to be my own “gogo boy”. And that’s kind of gone in a weird direction, I think.

Hans Nieswandt

Hans Nieswandt has been a respected and active protagonist in the world of DJ and club culture, electronic music production and pop journalism since the 80s. Extensive DJ and lecture tours have taken him around the world. Both as a solo artist and a member of Whirlpool Productions, six albums and countless remixes have been released to date. For years, Nieswandt has been mixing his own radio show every Wednesday night on WDR 1Live. After plus minus acht. DJ Tage, DJ Nächte (2002) (ie. Plus Minus Eight. DJ Days, DJ Nights) and Disko Ramallah - und andere merkwürdige Orte zum Plattenauflegen (2006) (ie. Disco Ramallah, and Other Strange Places to Play Records, KiWi Köln published his third book: DJ Dionysos - Geschichten aus der Diskowelt (2010) (ie. DJ Dionysus - Stories from the Disco World).

Comments

Comment