We run into the Bauhaus more often than we know – and not just while out shopping for furniture. Some of the design school’s maxims have found their way into everyday speech as well.

By Nadine Berghausen

“The ultimate goal of all art is the building!” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank

“The needs of the people before the need for luxury” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank

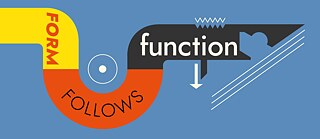

“Form follows function” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank

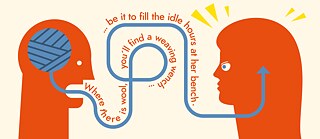

“Where there is wool, you’ll find a weaving wench, be it to fill the idle hours at her bench.” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank

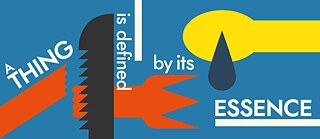

“A thing is defined by its essence” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank

“Positively unfriendly” |

Illustration: © Tobias Schrank