Berthold Franke

Legend, Heimat, traffic jam

From the darkest chapter of the 1930s, generations of Quartets-playing kids since the ’50s, car-free Sundays in the ’70s to autobahn exits full of poetry – Berthold Franke’s lead article takes us on a journey through almost a hundred years of (West) German autobahn history. Sit back and enjoy!

In the post-war period, the “Autobahn” was often cited as proof that not everything during the Hitler era was bad, a claim repeatedly asserted to relativise the country’s recent past. There was no doubt that the system of “federal highways” was a remarkable achievement. The cautiously regained confidence of the German people during the post-war period of economic recovery thus connected to a myth the Nazis had cleverly presented during their period of growth in the 1930s. The construction of the autobahn, a nationalistically and ideologically charged project, was a central element of Nazi propaganda. And the German people saw the large-scale construction project and job creation scheme, purportedly devised by the “Führer” himself, as proof of his genius.

But planning had begun much earlier, and the first stretch of the autobahn linking Bonn and Cologne was completed in 1932. The Nazi leaders swiftly seized upon the idea of a nationwide network of highways, turning it into a prestige project that was to subsequently hold a significant technological and political fascination. The vision of the new “Great Germanic Reich” was bolstered by a map crisscrossed by an impressive network of highways. It promised a technically advanced, dynamic and mobile future in which even ordinary people would soon be able to travel by automobile if they worked hard and saved hard. The car was known as the “KdF-Wagen”, named after the Nazi-run leisure organisation “Kraft durch Freude”, or “Strength through Joy”. [1]

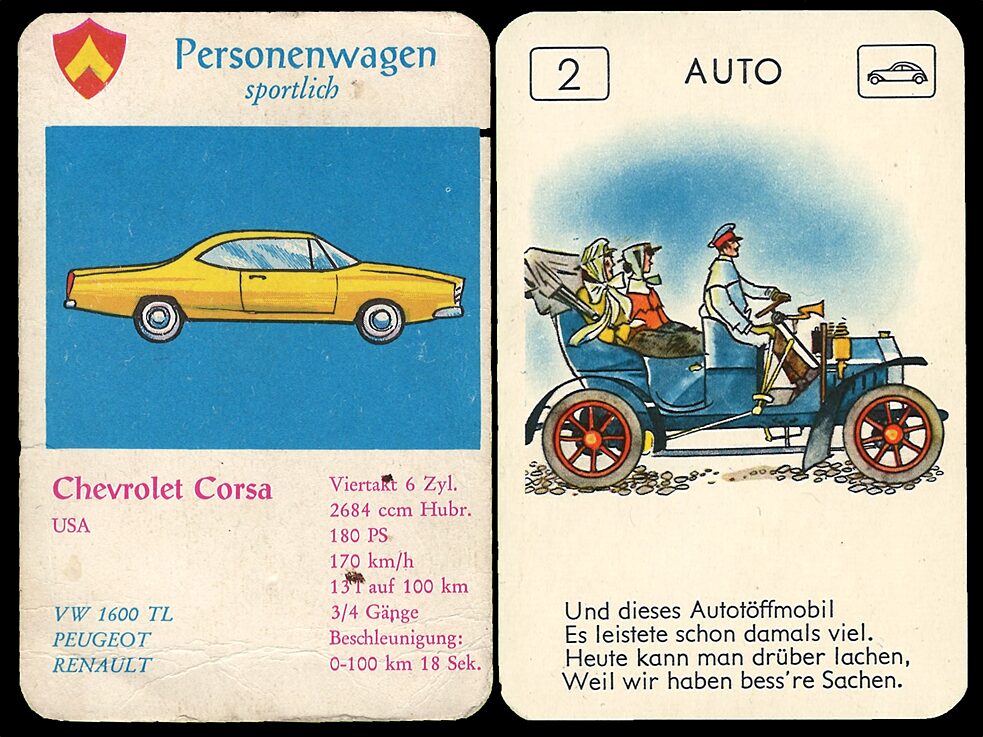

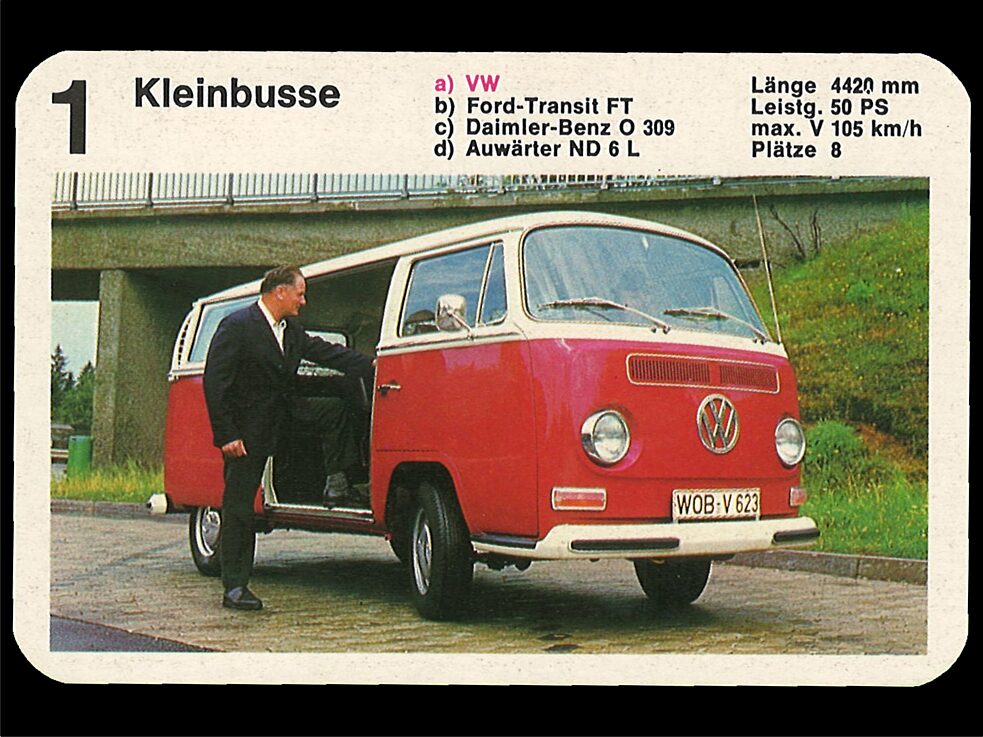

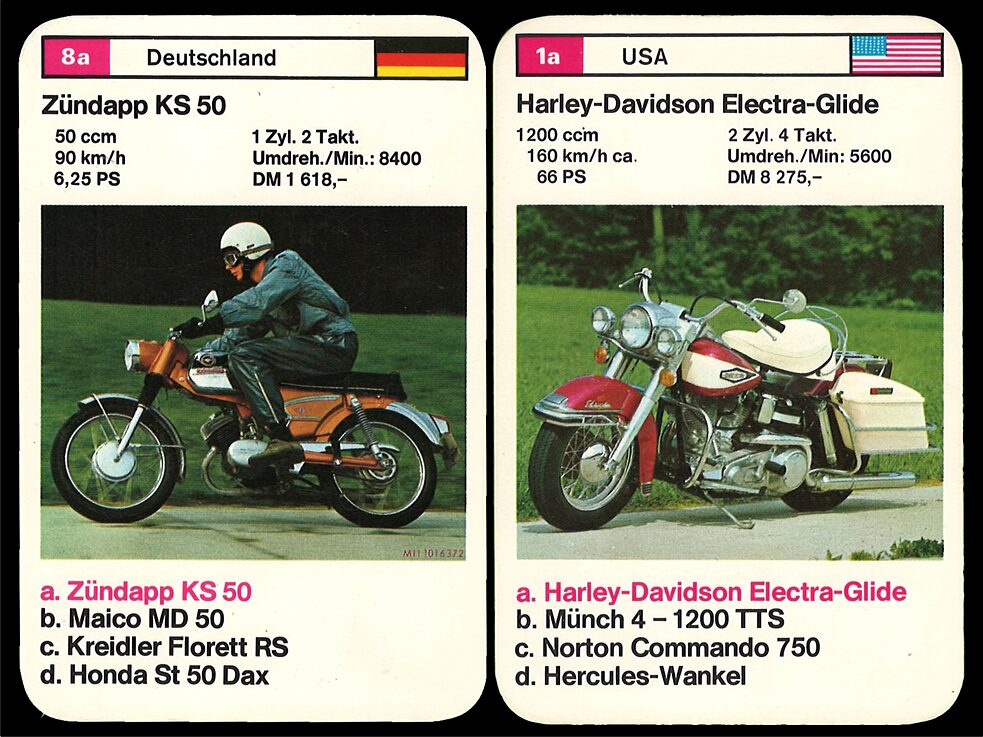

From 1938 onwards, according to the propaganda, every productive German should have the opportunity to own such a vehicle (final price 990 Reichsmarks) if they saved a minimum of five marks a week. For the production of these vehicles, a town was established in Lower Saxony in the same year. However, not a single KdF ever reached any of the many families who were diligently setting aside a portion of their income. Instead of producing cars, the town soon became an important centre of armaments production, and it was only after the war that it became known as Wolfsburg. But car production eventually resumed and the iconic “Volkswagen”, based on Ferry Porsche’s KdF design, became the German people’s car which has shaped urban landscapes and highways in the West since the 1950s.

The ’50s: Volkswagen and “schlager” kitsch

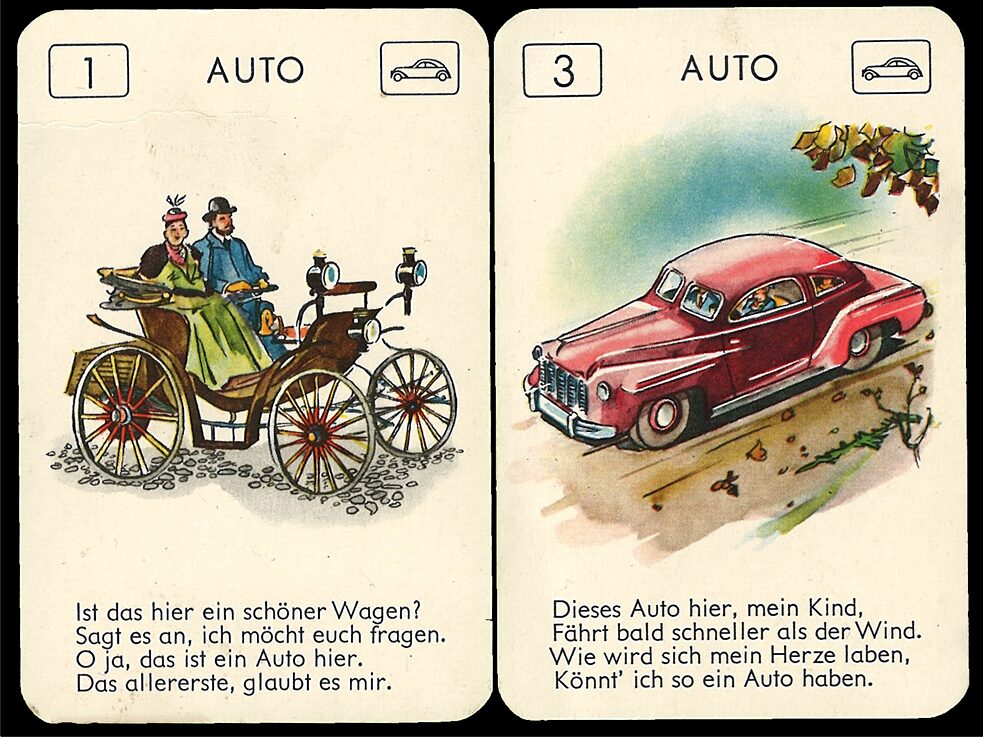

The economic recovery of the recently defeated nation – now cruising along the autobahn in their Volkswagen cars – reflected a culture in which the German people, who were needed during the Cold War, were given a new opportunity through hard work, under the watchful eye of the victorious powers. After all, their labour was needed during the Cold War era. The fact that the new post-war “autobahn myth” was subliminally linked to the old Nazi propaganda likely occurred in the collective unconscious of a nation still grappling with a lingering trauma. But it does provide a valuable insight into the country’s process of modernisation, which had to tread a fine line between restoration and democratisation.While images of bombed-out cities served for many years as a constant reminder of war and defeat, the German people did their best to seek refuge in the private domain. The void left by the Nazi legacy was filled by popular culture influenced both by attractive cultural exports from the US and escapist schlager kitsch and wholesome Heimat films from Germany. The great promise of relief and prosperity, however, was fulfilled primarily in the realms of the new mass consumption, the most coveted item, of course, being the automobile.

Escaping destroyed cities – finding freedom on the autobahn

And this automobile came to symbolise the longing for an intact, unscathed world, a means of escaping the destroyed cities and finding freedom – on the autobahn. It is no overstatement to say that people were captivated by this construction, universally admired for its dynamic expansion, for reasons far beyond its practical function in transportation engineering. The autobahn was the fruit of hard labour by many and an opportunity for all (there were no user charges). Beyond its utilitarian value, it became an immersive work of art, beguilingly connecting road and landscape, technology and nature, serving as a refuge for those who had suffered so many losses and so desperately longed for a new home.The experience of travel was as important as the destination, with cars and highways promising a new kind of freedom. This was not unique to Germany, but here the appeal was defined by a tainted past and the complex interplay of repression and compensation. With every newly constructed kilometre of road, with every newly connected town, the old myth gained new momentum. The devastated cultural nation found a fresh, contemporary identity in a modernised and technically advanced infrastructure, a place where people could escape from the past but also find confidence in a new technological and economic future.

The introduction of the Deutschmark prompted a surge of renewed national pride. The feeling that “We’re someone again” gradually spread in the West, especially after Germany won the World Cup in 1954. Another proud comment referred to the autobahn: “No one can match this.” The ambivalence inherent in the German identity – being either world champion or bottom of the league, with little acknowledgement of middle-ground achievements in any discipline – is exemplified most strikingly by the post-war West German autobahn.

Sunday strolls over the autobahn bridge

While East Germany achieved only a low level of personal transportation due to a much slower reconstruction process under harsh Soviet control until the end of the GDR (the autobahn network in 1989 was essentially the same size as it was in 1945), the Federal Republic, integrated into the western network, invested enthusiastically in transportation infrastructure. The system of highways was rapidly expanded to match the increase in the number of cars. No member of the Bundestag in Bonn could afford to appear before voters and not announce new routes and connections within their constituency.A younger, hard-working “sceptical generation” (Helmut Schelsky), disillusioned by the war and with a world view defined by technological progress, was also socialised in this way according to the aesthetics of mobility. An automotive future was sold as a “brave new world” and permeated everything from toys to advertising. Even smallest details such as the iconic blue autobahn signs shaped their sense of home with every kilometre they travelled.

Sweeping bands of road, bridges and concrete structures, which we associate today with the destruction of the countryside, back then represented an admired, aesthetically charged vision of a brighter future. They captivated the imaginations of families, from grandfathers to toddlers, on their weekly motoring trips. Even those without a car set off on ritual Sunday strolls across an autobahn bridge, where they marvelled at the roaring traffic and children waved eagerly at passing vehicles in the hope that the anonymous road users speeding under their feet would wave back.

Oil crisis and Kraftwerk – the ’70s

That was a long time ago. The autobahn myth probably started to wane in the 1970s, when the main sections of former West Germany’s network, which still exist today, were being built. Its first major setback came with the announcement of four car-free Sundays across Germany at the end of 1973 in response to the oil price crisis. Images of cyclists and roller-skaters taking over the autobahn are part of the iconography of old West Germany, while Kraftwerk’s seminal Autobahn, with its cool, monotonous beat, became the definitive soundtrack of this era. Retrospectively, this song – rightly hailed as Germany’s greatest pop music hit – now sounds like a swansong to a fading cultural icon.Since then, the number of autobahns has increased rather than decreased: from 2,000 kilometres in West Germany after the war to 9,000 kilometres by the time of reunification. The increase to over 13,000 kilometres since then, however, is due largely to the construction of new routes in the east, a project that lacked the emotional resonance and overarching symbolic force of initial autobahn construction. Parts of this project also involved the improvement of sections that had not been maintained since their construction in the 1930s.

But even on the generously extended new autobahns in the east, a sense of home no longer readily emerges. Certainly not for the many millions of commuters who spend a significant portion of their lives there, and not always when the traffic is flowing. According to statistics from the Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobilclub, over 700,000 traffic jams clogged German autobahns in 2019, with a total length of over 1.4 million kilometres and a total duration of over 520,000 hours. To prevent this immense traffic overload, especially during the summer holidays, a complex schedule for staggered school holidays is devised among the 16 federal states every year. The idea of the entire nation getting into cars and going on holiday all at the same time – as is the case in France – is enough to make traffic experts break out in sweat: an autobahn nightmare.

Freedom of the road for free citizens?

For generations of autobahn users, the term “Freie Fahrt”, freedom of the road, encapsulated a feeling of liberated mobility and self-expression. The question of a speed limit, still a highly charged ideological issue today, divides the Republic into two camps. Although opinion polls show that after years of overwhelming majorities against a speed limit more than half of survey participants now favour endorsing an environment-friendly, resource-saving intervention, a still strong minority of over 40 percent, along with Germany’s traditionally powerful automobile lobby, succeeds in swaying speed limit discussions in their favour in every new legislative period. Formally introduced in 1978, the “recommended speed” of 130 kilometres per hour holds little more than symbolic significance. Effectively, this means that on 70 percent of autobahns, you can still hurtle along as fast as you want.This is a peculiar privilege Germany shares only with the Isle of Man in Europe and distant motoring havens such as Myanmar, Burundi, Bhutan, North Korea, Haiti and Somalia. Perhaps the strangest outcome of this anachronism, which says a lot about our country, is the emergence of a niche product in international tourism. Visitors (most notably from China) are offered a unique package: in the early hours of the morning, when traffic is light, famous, high-performance German cars wait at service stations along designated sections of the autobahn for tourists to put pedal to metal: limitless speeding up to 280 km/h, all inclusive.

Excess and everyday life – every autobahn user in Germany knows that unnerving feeling when a vehicle appears out of nowhere in their rear-view mirror, edging uncomfortably close to their bumper and flashing headlights as a signal to move over, so that they can continue to lead-foot it down the left lane. This behaviour not only constitutes the legal offence of coercion, it epitomises the notion that the autobahn is lawless, uncivilised territory, a stage for regressive, archaic displays of male dominance, where the “might of the right” reigns supreme: the autobahn, a realm without laws.

But generally speaking, the autobahn has become a safer place. Since the highest number of autobahn fatalities was reached in the early 1970s, figures have dropped by 75 percent to a few hundred a year. Advancements in safety technology, compulsory seatbelts, thousands of kilometres of crash barriers as well as 16,000 “emergency call points” (a technology that predates mass mobile telephones) all play a part in this trend. So the generally cautious autobahn users very often drive through their country shielded from the environment by “noise barriers”, most recently experiencing congestion caused not just by traffic overload but by roadworks. And these, in turn, are the result of a large backlog in road construction investment.

Trucks, bridges and poetry in Feuchtwangen

Expansion of the autobahn network has ground to a halt with some members of the Bundestag now appealing to voters with campaigns to prevent the development of new routes. But the significant surge in the movement of goods since the fall of the Iron Curtain, as reflected in huge increases in truck-based transportation, is also becoming a serious threat to existing autobahn infrastructure. Germany is Europe’s primary east-west and north-south transit country, and its roads are groaning under the burden of long-distance freight transport, which has more than doubled since 1991 to over 500 billion “tonne kilometres” annually. While still a lot less than car use (around 850 billion “passenger kilometres”), this is a considerable burden in terms of CO2 emissions and space requirements, and also in terms of the immense damage heavy goods vehicles are causing roads and bridges. Experts estimate that one truck puts about 40 times more strain on infrastructure per kilometre than a passenger vehicle.Put simply, this means no fewer than 4,000 of Germany’s 40,000 autobahn bridges are currently in urgent need of reconstruction. Most of these structures were originally built for car traffic in the 1960s and 1970s, when the huge, destructive volumes of trucks following reunification were not yet a pressing concern. On the A45, or “Sauerland Line” alone, once hailed as Germany’s “most beautiful” (and consequently most costly) autobahn with its breathtaking bridge vistas, 60 bridges now await major redevelopment. A nightmare for transport planners in the Berlin ministry, and even more so for local residents facing years of roadworks and diversions through the heart of their towns and villages.

The dawn of a new autobahn era? Whatever the case, it’s clearly a wake-up call for transport planners to reassess their priorities. And yet the joy our parents once felt while cruising along the autobahn is still tangible. Take the A6 in south-west Germany, for example, where between Heilbronn and Nuremberg a sign suddenly announces the exit to four small towns whose names transform the place into pure poetry in the most melodious-sounding German: Feuchtwangen, Dorfgütingen, Schillingsfürst, Dinkelsbühl.