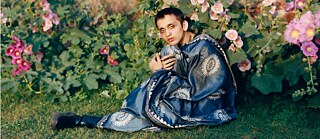

Pratyan Chakraborty

“I basically grew up being an introvert”

Pratyan Chakraborty is a poet, model and queer activist. In this interview, held in a park on a hot day, they talk about being queer in New Delhi and how they got into writing poetry and modelling.

By Katharina Holzmann

At five o’clock in the afternoon, it’s finally not quite so hot. The perceived temperature of 39 degrees drops to maybe 37 degrees, and the sun is low enough that the magical light that makes all the colours glow promises good photos. We meet Pratyan Chakraborty, poet, model and queer activist in Deer Park in South Delhi. In some places it looks more like a jungle, with deer, peacocks, flying foxes, monkeys, chipmunks, dogs and guinea pigs (!) living alongside ruins from the Muslim era. The park is located in one of Delhi’s wealthier areas. It’s surrounded by a small party district, which is also home to the city’s only two “real” clubs (apart from the hotel clubs) and many bars. This is a neighbourhood that could be described as East Asia Town (although East Asia starts here in Nepal), which means that there are a lot of young and somewhat hip people hanging around. Two friends walking around the park with joints. Some boys and girls are making pretty impressive dance videos (not for TikTok, because that’s banned here). Young people hang out in the cafes, drinking bubble tea. Many women are wearing short skirts. Overall, there’s little to suggest that you’re in a country where a far-right Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, has been in power for ten years. While we’re in India, elections are coming up. As soon as you leave the little islands of liberal bourgeoisie, you realise how serious the situation is. Whole blocks of houses and villages are plastered with the neon orange BJP flag. The TV in a restaurant is showing another arrest of a member of the opposition. In some neighbourhoods, houses where Muslims live are marked with a red X. At one point we saw a rather aggressive, neon orange campaign team on motorbikes. Just enough context to understand that the seemingly relaxed atmosphere through which we move with Pratyan is a fragile one. Amelie takes a photo of Pratyan in their dazzlingly beautiful saree and it’s not long before two or three men stop and insist on taking selfies with me, Amelie and also with Pratyan.We join in for a while, but it becomes too much for all three of us, so we walk on through the park in search of a quiet place to chat.

P: Pratyan Chakraborty

K: Katharina Holzmann

A: Amelie Kahn-Ackermann

P: If you are white, they are like, oh my god! Silly people. Sometimes they consider me white, that’s why they asked me as well. This one time I was literally in my hometown and there were two Bengali girls, they couldn’t tell that I am Bengali and they were like, can we take a photo with you? It doesn’t come as a negative at first, because they are being very sweet to you, but then the thing is, you don’t know what those people are doing. They ridicule you, they make memes out of you and then they start talking about you, and it gets so messy. It’s just really weird. And they make things out of the most basic things, like the clothes you are wearing or even in university: if you’re reading a book they would make something out of that as well. So I read a lot of Sylvia Plath, I really love her. So they make these jokes about me being mentally unstable. They make things out of everything they get. You just show them something and they will make something out of that.

Pratyan Chakraborty | Photo: Amelie Kahn-Ackermann

P: Yeah and they wouldn’t have left. And you don’t know, sometimes they even get violent. They are like: who do you think you are? This one time I said this to a guy and he followed me with his car for three days. That’s Delhi. Especially in main and north India, it’s really scary.

K: But is Delhi kind of more liberal in some parts?

P: Since it’s the capital, there are queer spaces in Delhi, where you can be who you are. But other than that, it’s pretty much the same. Also Delhi is literally called the rape capital of the country. It’s very, very scary. But in India, where will you go? Because the only possibility is either going to Bombay or Delhi, so it’s pretty much the same. But then the community here is probably very strong. There is a lot of resistance, a lot of movement, a lot of protest, a lot of demonstrations.

Since it’s the capital, there are queer spaces in Delhi.

K: How do the protests get seen by the public? Are there a lot of people going to them?

P: Not good. If it’s something like a pride parade, then it’s a lot of people. Last time it was about 2,000 people. But if it’s just a protest organized by college students or something like that, then it’s not that many people. But it’s very regulated and oppressed. I remember last year I was at a protest and there was this deadline that the police gave, a permission to be on the streets until 5 p.m. only. It was one minute after 5 and I was leaving. This one police officer comes up to me and he literally beats me and a friend with a stick.

K So they’re saying it’s kind of legal what you’re doing, but let’s wait until you do one thing wrong …

P: Yeah, but it was one minute. One minute. They were like, we had enough of you. Yeah, so that’s basically the current government.

K: But over the last 10, 20 years, has there also been positive change in any way?

P: There has been positive change in the sense, if you think about it, it’s an era of globalization, right? So in that way, we got access to a lot of information, we got access to a lot of things that were not there before. So in that sense, of course, yes, we get to dress up more, we get to go out more, but in the sense of human rights, it just keeps on getting worse. So there was this Babri Masjid thing (a 16th century mosque in Uttar Pradesh, destroyed by Hindu nationalists in 1992 because it was believed to have stood on the site of a Rama temple before Muslim rule over India. As a result, 2,000 people died in mob violence, most of them Muslims; a Hindu temple has just been inaugurated on the site of the mosque, Google it, ed.). I don’t know if you have heard of it. It was a communal violence thing. And the current government recently passed a bill about the school syllabus and they’re calling that thing, that was basically genocide and riot, a political movement. Because that way it benefits them, the majorities. So they are teaching kids that it was something good. But it was not. A lot of things are going on and the election is coming up now. We hope that this government goes away. But it’s very corrupt now.

In the sense of human rights, it just keeps on getting worse.

P: Yeah, there will be. Definitely. And also, even if another party, like the Congress (the Indian National Congress, one of India’s current eight national parties, is considered relatively socially liberal and secular, and was long led by Indira Gandhi, ed.) comes, it’s going to be pretty much the same, but at least the Congress government, the ministers and people are educated, they know what they are doing. So that’s a good thing. Naendra Modi, our Prime Minister, doesn’t have a college education. And I think a good education is really important to be able to run a country. It’s not wrong of me to expect my Prime Minister to be educated. So at least the congress, they have studied, so they make schemes for education and students and all. There used to be a lot of scholarships that this government shuts off. And now they are only spending 5 percent of what they used to spend on education. You know, when people are educated, they are also asking for things. And when Trump came, they spent billions of dollars to just cover the slums instead of spending money to improve the lives of people being stuck there. Instead, they put walls around the slums. And they did the same thing again this year when G20 was happening. They say all these big things on global platforms, they go abroad and say like, oh my god, development, but nothing is really happening.

It’s not wrong of me to expect my Prime Minister to be educated.

K: We talked about this a lot, because also in Germany, the right parties are growing and more people vote for them. And it’s the same all over Europe. And in the US… It sometimes seems as if the whole world wants to go back in time. You have this feeling, especially in countries like Germany, also in Italy and France, that the political mindsets have achieved a lot of development and good things, but now – for example in Italy – they just took away the right for same sex couples to both be the legal parents to their kids. Only one is now the “official” parent.

P: There was a huge petition going on and a case in supreme court for same-sex marriage in India last year and they said that the court literally put a hold on it and they were like: We will take six months to figure it out and then we will come up with our decision. And the court said later that we don’t get to make this kind of judgment, so we will ask the parliament to make it. You are the supreme court! Why are you asking the Parliament when you know pretty well that they are not going to do anything. And they of course didn’t legalize it.

K: Do you want to tell us a little bit about your poetry? How you started, where it comes from?

P: So I basically grew up being an introvert. I mean, I used to be obese as a child and that’s why I never really had friends in school and I never really had friends growing up. I used to sit at my place and just read poetry and literature for hours and hours. That’s how poetry started for me and especially as I am Bengali, Tagore (Rabindranath Tagore, bengalischer Schriftsteller, hat als erster Nicht-Europäer den Literatur-Nobel-Preis gewonnen, Anm. d. Red.) and other people influenced me. So yeah, that’s how I started: reading a lot. I love literature. This one time I was like, why not write? I was just four back then. And I wrote a pretty stupid thing about a basil tree, a basil plant. We had a plant and I watered the basil, I water the basil, if you just come, something like that, it was a rhyme.

I love literature.

K: Do you still have all your poems from when you started writing? I would love to read the poem about the basil tree.

P: Not really. So, there is this weird thing that happened. I used to write in Bengali at first because I went to a Bengali middle school. I didn’t really learn English in school. I was writing Bengali and my mom once found my poems. So when I was in school she would burn my whole diary, literally destroying all my poems. And when I came back I was like, why did you read it? And she was like, I did it for you. It was too dark. I was like, yeah, you were not supposed to read these things. I was 13 and I was like: I’ll have to learn a new language. So she can’t understand. And then I started putting stickers and colors on my phone and I started writing in English.

My mom once found my poems.

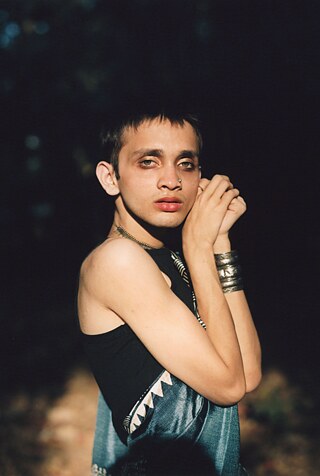

P: So Nisar Gandhi, a photographer, he is brilliant, was doing a campaign for Shreya. I was in front of the camera for the first time and he tried to shoot me for three hours. And I just didn’t know what to do. I was just standing like this. And now I’ve been modeling for almost four years. It went quite fast with just so many different things. And I was a person who was against fashion, you know, I hated it. I never imagined that I would be doing this dressing up and stuff. I was a person who was like: Why do you even need to dress up? Why can’t you just wear the t-shirt and a basic pajama and go out? And now I’m up to date about everything that’s going on on the runways and stuff. Even sometimes it feels like it hasn’t been four years. Because it just shifted a lot, you know? So like, from nothing to poetry to fashion. And now I have this contract coming up for a film, a feature film. It’s gonna be my acting debut! So my genre is shifting again. But poetry and writing is something that I will always do.

Pratyan Chakraborty | Photo: Amelie Kahn-Ackermann

P: Yes, so the thing is that I basically got outed in my school. I came out to one of my seniors and he outed me to everyone about my sexuality when I was 16.

K: How hurtful.

P: And then a lot of bullying and shit started happening and I was like, I cannot be here. And also I couldn’t risk my parents finding it out. So I was like, maybe I should just go somewhere. So I came to Delhi when I was 17. And I started working here, I started getting homeschooled. I was just roaming around here and there. I was fighting all those things for one and a half years. But then when I came to Delhi I started performing and this one time one of India’s lead newspapers, New Indian Express, they interviewed me and it got out. I thought my parents don’t read English newspapers so they wouldn’t find it out. But the newspaper posted it, they put an article on their website as well. And somehow it landed on my uncle’s Facebook page and he sent it to the whatsapp group. So I was glad I was in Delhi. And like it’s kind of weird now because my parents don’t really take it well. So my father is in denial, he doesn’t really talk about it. He just pretends, he just doesn’t really bring it up. He just acts like he doesn’t know anything and everything is fine. And my mom says, you be what you are, but don’t start dating anybody. Don’t show it off. I don’t have any issues with you being queer, but be queer to yourself.

A: Why are moms always a little bit better? Every time I hear these stories, I always have the feeling that moms often at least kind of try to understand what’s going on.

P: At the end of the day, she’s a woman. So there is this sense of solidarity, that even if she was awful at times, I understand why she was. Because she got married when she was 16. She couldn’t finish her school. She wanted to be a lawyer, but then she couldn’t do that. She became a mother at 17. So she had been through a lot. So now I feel like even if she’s harsh at times or whatever – I recently read this quote on Instagram. It said something like as a daughter I have a lot of anger against my mother, but as a woman I feel only love for my mother. I don’t really hold things against her. When you can understand suffering in any way, you have more understanding for others.