Cherrypicker

Inherited Misfortune

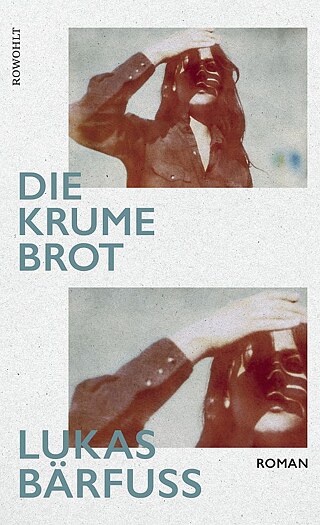

In his new novel, Lukas Bärfuss again focuses on the existential hardships of people in modern, capitalist society. Here he tells of the fate of a single mother.

By Holger Moos

The very first sentence indicates that the protagonist’s fate may be predetermined by her family history: “No one knows where Adelina’s misfortune began, but perhaps it began long before she was born, forty-five years before, to be exact.” At that time – in the days of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy – Adelina’s grandfather, who came from Trieste, had studied law in Graz, but had read the forbidden writings of Cesare Battisti. Battisti fought on the side of Italy against the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the First World War. Adelina’s grandfather also becomes an ardent Italian nationalist, joins the Italian troops and, after the end of the war, listens with fascination to a “splendid” orator named Mussolini.

The fate of Adelina’s father Mario is also tragic. When Mario’s nationalist father learns from an unknown cousin that Slavic blood supposedly flows in the veins of his wife, who died young, and thus also in the veins of his son, the father punishes his offspring with contempt, even sends the delicate, languorous boy into the military – although he could have prevented it – and thus into the Second World War. He doesn’t want to waste his life “raising a Slav.”

Gradual dejection

Mario returns from the war, but is once again disowned by his father. He is ordered to leave his hometown of Trieste. The young man, already scarred by life, abandons himself to his dreams of an intellectual life in Switzerland and at the end of his life leaves behind nothing but debts. The narrator characterises Mario’s life path as follows: “Misfortunes didn’t happen, life was misfortune, it flowed along and knew only one direction, towards gradual dejection.”The characters’ fates repeat themselves. Mario is also disappointed in his daughter. Adelina has a reading and spelling disability, and thus no access to the world of books, of the mind, so beloved by her father. Even though he knows that no one is to blame, he can’t help but take “his daughter’s stupidity” personally: “He believed his daughter wanted to punish him, in an ugly, evil way, as his father had punished him.”

Adelina, who is by no means stupid but musically gifted, works after school in a small laundry, where she also benefits from her skills as a mending seamstress. After her father’s death, Adelina’s mother asks her daughter to accept his inheritance despite her father’s debts. After initial resistance, Adelina complies. The precarity trap is thus snapped shut, especially as her mother makes off to Italy with a new husband shortly after her father’s funeral. Now Adelina is stuck with the inherited debts – a burden that is too great, as her further life shows.

Moral drive

Adelina can no longer afford to continue her apprenticeship in the laundry and hires herself out as an assembly line worker in a soup factory. Soon she meets an Italian man, falls in love, and becomes pregnant. Salvatore works in civil engineering, is only ever given a limited work permit to go to Switzerland, and one day doesn’t return to her. Adelina has an even harder time as a single parent in debt. Caring for her daughter while working is almost impossible.Nevertheless, Adelina doesn’t give up, braces herself against the unfortunate circumstances and works as a barmaid. When she meets the wealthy Emil, he even settles her debts. Alone, she is not happy in this bourgeois environment, breaks free and ends up, in the year 1973, in the milieu of the Red Brigades. But instead of gaining independence, she is lectured to and manipulated by the leader of the Milanese terror cell. Adelina’s poverty again has its price, which her own daughter also pays. The inherited misfortune will possibly continue into the next generation. Bärfuss has announced that Die Krume Brot is the first part of a trilogy. We’ll see if he picks it up from here.

With this novel, Bärfuss presents a story that illustrates the theme of social determinism. The response to this has not been entirely positive. In the NZZ, for example, Roman Bucheli criticises both “errors of craftsmanship,” which he says are evidence of Bärfuss’ lack of interest in his main character, and also calls the novel “a poorly concealed enactment of his programmatic theses.” To be sure, the characters are somewhat formulaic, but Bärfuss puts his finger in the wound of immovable social inequality. The fact that the author’s moral impetus clearly shines through – when he received the Georg Büchner Prize in 2019, his “ability to analyse society” was rightly praised – does not detract from the novel’s narrative power.

Hamburg: Rowohlt, 2023. 224 p.

ISBN: 978-3-498-00320-3

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.