Translating comics

Puns in speech bubbles

What make translating a comic unique? What kind of issues do translators face? Five translators talk about what they do every day.

By Ralph Trommer

The comic market is one of the few book segments that can boast steady growth figures. Countless new publications come out every month, and many are foreign-language titles that have been translated. Comic translators face a range of challenges unfamiliar to those who work with novels. They have to reproduce puns and dialect in another language so that it sounds natural and still fits into a speech bubble. Five translators tell us what they feel makes working with comics unique.

Limits of the speech bubble: you can’t just turn “adios” into “auf Wiedersehen”

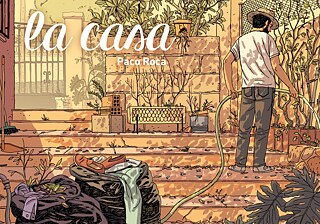

André Höchemer lives and works in Spain. He has translated a lot of Spanish comics (Clever & Smart) and graphic novels (Die Heimatlosen, Der Riss, La Casa) into German in recent years.

“The goal of a translation – whether it’s a comic, non-fiction or an instruction manual – is always to do justice to the original and provide the readers of the target language with a text that is just as easy to understand. What makes comics unique is the close relationship between the words and images. The words in the panels and speech and thought bubbles are limited by the available space, and the translation has to fit in there as well. If you have ‘adiós’ written in a small speech bubble, you can’t just turn it into ‘auf Wiedersehen’ because it won’t fit.”

Dialects and slang: take your cues from everyday speech

Frank B. Neubauer translates works from English into German (including Sandman, Geschichten aus dem Hellboy Universum).

“Language is more alive when you take your cues from everyday speech. This is why there are more puns, idiomatic language and slang in comics. Mangas also often feature the dialects of individual regions. Apart from that, I try to listen to my eleven-year-old son and take the bus and train when I can. You pick up a lot.”

Vocabulary: German offers more variety

Berlin-based Katharin Erben translates the work of Swedish comic artist Liv Strömquist (Der Ursprung der Welt, Ich fühl’s nicht) into German.

“One challenge is that the vocabulary of the two languages is diverse in different ways. The German language frequently offers more variety. When describing an activity, Swedish might have three possible verbs, whereas there are five alternatives in German.”

Cultural differences: “The relationships among the characters are more important”

Japan expert Verena Maser from Nurnberg specializes in translating mangas (including Das Land der Juwelen, Café Liebe) and anime.

“There are a lot of words in Japanese that simply cannot effectively be translated into German. In a similar way, Japan’s unique school culture plays a major role content-wise, since many mangas are set at schools. So every now and then, I am surprised by how well some mangas are received by a German audience. Apparently it is possible to enjoy a story without understanding the cultural background – or perhaps the relationships among the characters are more important overall than the setting”.

Different senses of humour: “compulsion to make puns“

Based in Freiburg, Ulrich Pröfrock (Donjon, Herr Hase, among others) is an expert when it comes to translating French comics.

“The French and the Germans have different senses of humour, which can increase the level of difficulty. In France there is a compulsion to make puns. In Olympia in Love by Catherine Meurisse, for example, the allusions refer to classics from French film, art and literature. Meurisse references things learned in French schools, like a popular poem by Victor Hugo about Napoleon that hardly anyone in Germany is likely to know. In Esters Tagebücher, Riad Sattouf uses Verlan, a slang spoken by young people in which the syllables are reversed and that cannot be directly translated.”