Cherrypicker

Of women and their objects

The lives of women in the past are often presented as trivial. Annabelle Hirsch contradicts this theory. In a compassionate account, she guides readers through the many facets of women’s history, based on 100 objects.

By Anna Berchtenbreiter

A few months ago, the “history repeats itself” trend was to be seen all over TikTok. You saw women doing seemingly everyday things, such as plaiting hair, reading books or knitting, and then chatting about them with an alter ego, a “women from the past“. These women concluded that while they lived in different eras, the activities they engaged in were the same. The videos imparted a sense of connectedness and understanding, and a touch of melancholy.

That is precisely the feeling you have when reading Annabelle Hirsch’s Die Dinge. Eine Geschichte der Frauen in 100 Objekten (A History of Women in 101 Objects). This non-fiction book opposes conventional historiography with its predominant narrative of outstanding men performing heroic deeds. Although you tend to read less about women, that does not mean they made no active contribution to world history. With few exceptions, however, they are seen merely as “extras” rather than as active players. That is illustrated by an anecdote in the author’s introduction. When she told an acquaintance about her idea for the book, he joked patronizingly, “Women and objects? Women are objects!“

The private part of history

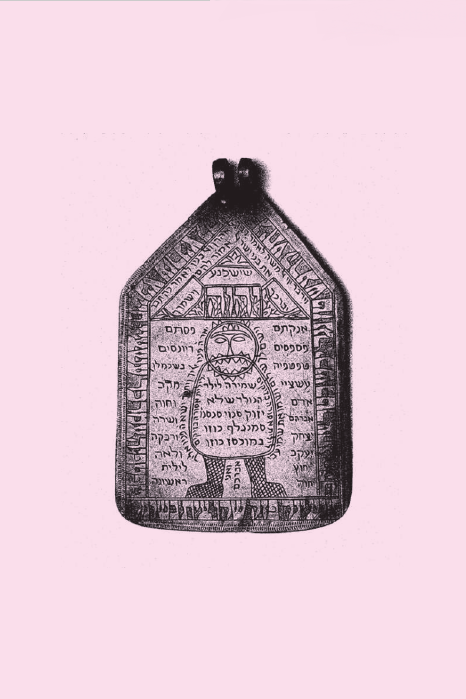

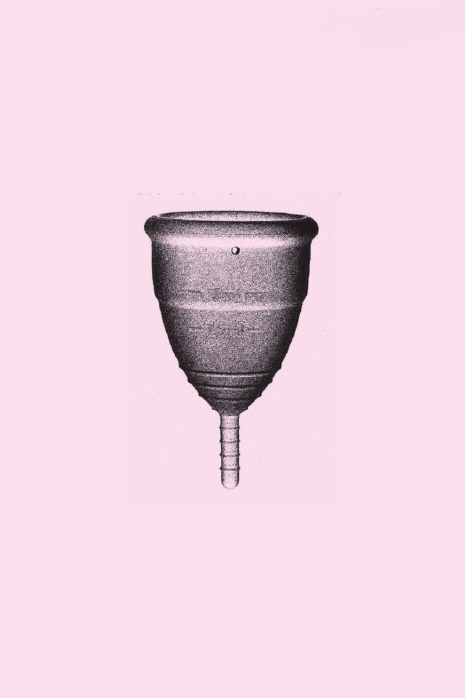

On 400 entertaining pages, German-French journalist Annabelle Hirsch shows that women in history were definitely not objects, but actors with a mind of their own. She writes about the small things, the intimate, private, often forgotten parts of history: scissors, amulets, garment bags, corsets, dildos and much more. Things that moved, accompanied and liberated women. The book presents a personal collection of objects, which, the author believes, is subjective and strongly influenced by her own background.Devoting three pages to each object, she tells lively stories about apparently trivial things. Some seem familiar, while others are surprising. All the statements are informative. Hirsch wants to show how diverse and non-linear female history is.

You follow the author on a chronological journey from approximately 30,000 BCE to the twentieth century, which is presented in detail, up to the end point in 2017. You can marvel at black and white pictures on a pink background of items such as a healed femur, a witch dance mask, a menstrual cup and Kim Kardashian’s ring.

In the chapter about a so-called Lilith amulet, quite early on in the book and on the author’s timeline, you encounter the first woman in religious history. According to Hebrew myth, that woman was not Eve, but the rebellious Lilith. Unwilling to subject herself to Adam, she left paradise and was demonised as a child murderer, the personification of evil and Satan’s wife. It was believed that that an amulet could protect you against her. Later, we are relieved to learn, Lilith made a comeback as a free, uncontrollable woman, becoming a role model for Jewish feminists in the 1960s.

Many years and many pages later (Hirsch has arrived in the year 1900), you see the image of an unimposing hatpin. Why did it end up in the book? Because this sharp fashion accessory, sometimes used by women as a means of self-defence, struck fear in the hearts of men in big cities of the Western world. In 1903, for example, Leoti Blaker refused to allow a man on a stagecoach to continue to harass her. After he had touched her inappropriately several times, she plunged her three-inch hatpin into his arm, a story that hit the headlines.

Connecting with the past

Regardless of whether she is presenting a seventh-century BCE Sappho papyrus or an 1889 bicycle, Hirsch creates empathetic proximity with the women of the past in her book. You feel inexplicably linked with them. You feel angry for them, suffer with them or fete them for their courage and shrewdness. The author brings hidden things to light, the fabled “private” space that for so long was the only place where women could feel at home, and shows that women in the past were by no means as passive as many people now believe. The women of the past were present, they “took their place in history, they moved, changed and influenced things”, as Kristine Harthauer of SWR2 says in her review. And above all, they left traces you can see today if you care to look.”After finishing the book, you put it down, but the subject remains with you. What would you have put on your own list of 100 things? And what would that list be like after 2017? What traces do women leave behind? Are they perhaps as loud and conspicuous as the book’s bright-pink and orange cover? Time will tell.

Annabelle Hirsch: Die Dinge. Eine Geschichte der Frauen in 100 Objekten

Zürich: Kein & Aber, 2023. 416 p.

ISBN: 978-3-0369-5880-4

Comments

Comment