Cherrypicker | Literature

Breakfasting with Erika

They first they met on his talk show, then regularly at Vienna’s Hotel Imperial: Dirk Stermann, cult cabaret artist, and Erika Freemann, psychoanalyst. At the age of twelve, Freeman had fled from the Nazis to New York. Now she speaks with Stermann about her life in a way that is ever witty, touching, and quite entertaining

Erika Freeman was born Erika Polesiuk in Vienna almost a century ago, in 1927. She grew up in a Jewish family: her father was a physician, her mother was a teacher whose life was later depicted in film, in the Oscar-winning Yentl, starring Barbra Streisand. Erika Freemann told these and many more anecdotes in the Vienna television studio, captivating not just the audience, but the presenter. Dirk Stermann is a writer, cabaret artist, and TV and radio star with a cult following who was born in Duisburg and has long lived in Vienna.

At home in a luxury hotel

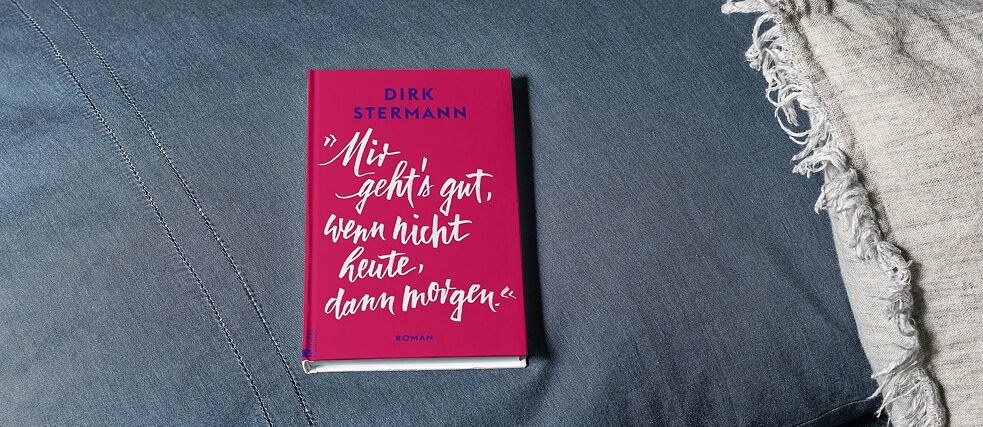

The television interview wasn’t the end, therefore, but the beginning of a delightful friendship. From then on, Dirk and Erika had special breakfast conversations over croissants and white coffee every Wednesday. The talks were rambling, funny, pointed, tragicomic and were eventually summarised in the book «Mir geht’s gut, wenn nicht heute, dann morgen» (I’m fine, if not today, then tomorrow). The almost centenarian grande dame of New York psychoanalysis, whose patients included many Hollywood stars, had undergone heart surgery in Vienna. Then Covid came along and prevented her flight home. Erika Freeman took up residence at the acclaimed Hotel Imperial and stayed for a while. As she notes with some self-satisfaction, “It’s my revenge on Adolf Hitler. He only stayed at the Imperial once. I live here.”It may be a minor triumph, but it came at too high a price: Freemann’s mother and aunt were killed in a bombing raid in Vienna in 1945, her father was deported to a concentration camp, and she herself spent her youth on the run and in an orphanage. As recently as 1961, a Viennese hotel receptionist refused her accommodation with the words “We don’t take Jews.” Now she was being waited on hand and foot in the luxury hotel, something Stermann benefited from as well, seeing as Freeman always dotingly gave him the unused but ever-replenished hotel toiletries.

Juxtaposition of past and present

In the book, on his way to see Freeman, Stermann makes observations of his adopted home – queues of tourists outside Café Central, defecating Fiaker horses – and the events that come to mind like Thomas Bernhard being a regular guest at the Bräunerhof. Or they stroll through the streets together and Freeman remembers her beloved mother, who didn’t survive the war. The breakfast conversations sometimes revolve around the finality of life but are at the same time invitations to savour it. For instance:Dirk: “Why we have to die?”

Erika: “Yes, so that we aren’t given too much time to destroy the world. Won’t you finally have a croissant?”

Comic situations are followed by looks at mostly abysmal aspects of recent history, serious observations are followed by a dry joke, there is a lot of talk of Jewish life and Jewish customs in Vienna and New York and about the particulars of psychoanalysis. Again and again, Erika Freeman sums up her outlook on life in memorable sentences, often in a delightful blend of German and English:

Friendly exchange

Although it may sound formless, the result is a unified whole; a multi-layered tribute to a charismatic academic who has successfully and fearlessly fought for her life, her profession, and her happiness and who correspondingly thinks and speaks positively, without negating or minimising the depths of human nature and historical disasters. The book, with its familiar banter and the way the two are attuned to each other, reads like a podcast made by best buddies. But it’s also an ode to friendship, to an affectionate and productive encounter between two people of different backgrounds and social status who are equally curious and empathetic. For this reason alone, it’s a pleasure to read, follow their conversations, and gain some new insights in the process.However, the extent to which the attack on Israel by the terrorist organisation Hamas on 7 October 2023 also represents a turning point for Erika Freeman becomes clear in an interview with Dirk Stermann. When asked whether Erika Freeman is fearful following the Hamas attack, he denies it and continues,

We sincerely hope that Erika Freeman will be able to celebrate her 100th birthday in more peaceful times.

Dirk Stermann: «Mir geht's gut, wenn nicht heute, dann morgen.» Roman

Hamburg: Rowohlt, 2023. 256 p.

ISBN: 978-3-498-00374-6

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.