Music

“Dreams also serve as legitimation”

From Stockhausen to Wagner: important composers from past centuries claim to have been inspired whilst asleep. An interview with musicologist Magdalena Zorn about dreams as a source of inspiration, artistic self-portrayal – and what dreamed music actually sounds like.

By Eleonore von Bothmer

Ms Zorn, your research area is the relationship between music and dreams. What’s your focus exactly?

I’m interested in the question of where the idea behind a piece of music comes from. In musicology we tend to study the material, the score and how it sounds – but not the inspiration.

And where does the inspiration come from?

Looking at what composers are saying, increasingly from dreams. Right into the era predating secularisation, artists frequently reported that their ideas were dictated by a divine power or had their origins in religious experiences. Things have changed in that respect since the 19th century, but artists still often claim that their ideas came from an external source – which does include dreams. We know the phenomenon from literature: Valéry with his dream journals, or surrealism – which quotes dreams as a source of inspiration are the perfect examples.

What’s the reason behind this development?

My key finding is that dreams often serve as legitimation for being able to realise specific compositional ideas – often unusual ones – and lend these compositions an autobiographical integrity. In other words, if a composer can prove that his work – in the context of formal music I only know of men – comes from the inner depths of his self, having been dictated to him in a dream by what you might call a higher power, then it adds a compelling, vital feel to his ideas. Something that extends beyond his own self.

Doesn’t this put his own work on a higher level too?

Yes, absolutely. A lot of self-stylisation is involved. In the highly differentiated field of literary autobiographical research this is recognised as a core element: When authors refer to experiences of immediacy in order to stage an epiphany that makes the work special. This includes Goethe’s childhood experiences for instance, or the religious enlightenment experiences of St Augustine. Dreams fall into the same category.

For which composers do dreams play a particular role?

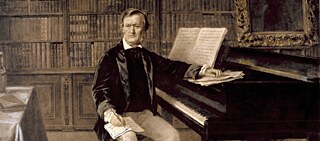

Richard Wagner was one of the first to repeatedly use dreams to inspire his compositions in the second half of the 19th century. He also thought that Beethoven’s style of continuous composition – which Wagner them continued to develop – could only have appeared in the “clear vision of the deepest world dream”. Karlheinz Stockhausen played an important role in the 20th century. In his work Trans from 1970 he composed a musical curtain for the first time: a densely woven scrim of string sounds from behind which music from beyond is revealed. It’s depicted like that on stage too.

It’s difficult to say. If a person claims to have heard something in a dream, that’s autobiographical territory. No one knows whether it’s true. Neither is it possible to say whether someone spent weeks thinking about a new composition and dreamed about it because of that – the way you process things that preoccupy you in dreams – or whether they dreamed it first and then incorporated it into the composition. Plenty of composers really do say “I heard what I composed in my dream”. Then their challenge is to recreate the unreal, the sound image from the dream, using real-world tools.

So is it even possible to translate inspiration from dreams so directly, and how does that work?

The interesting thing is that the dream as a visual sphere obviously dictates acoustic impressions to the composer. Personally I’ve never heard anything like this in a dream before. Maybe a synaesthetic coupling of auditory and visual impressions occurs in our dreams, so that music appears almost visually and then in reality is translated into audible content. Neurological analysis shows that musical and visual perception are linked with each other. The eye and ear operate together in the association cortex, which means that understanding music is an auditory as well as a visual process. Maybe musical people retain a dream impression in their memory in the form of a sound. What they then take with them from the dream is a translation into an auditory reality. One thing that speaks in favour of the synaesthetic interpretation – in other words the fact that dream compositions link the eye and ear together – is that the relevant works from the 20th century, like Stockhausen’s Trans or Mauricio Kagel’s Match, have strong visual components: they are stage concepts designed for the eye.

Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic and New Music, was also inspired by dreams.

Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic and New Music, was also inspired by dreams.

Can you appreciate that in musical terms – I mean can you tell when you listen to a piece whether it originates from a dream?

Stockhausen’s Trans for example uses a very advanced composition technique, which you can hear, and this incredible advanced character characterises all the dream compositions. The dream grants permission to enter new musical territory. Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde for example is said to be derived from a dream. Here we have an endless melody where all elements are joined together with everything else in a continuous flow of sound, with no division into individual sections anymore.