Comic art is not newly-discovered in the Arab world. Yet, previously limited to children’s stories and superheroes, comic art slowly gained momentum among Arab readers in the past few years. The difference, however, was the twist from fiction to nonfiction and the curiosity of emerging Arab artists to explore different genres and themes.

“Comics gave writing more magic,” says Rawand Issa, a Lebanese writer and comic artist.In 2019, Issa decided to document a story that negatively impacted her life and the lives of the people of the village she was from. With bright colors and bold facial features, Issa’s ‘Inside the Giant Fish’ follows a girl who loses her childhood memories because of the privatization of public beaches in her coastal Lebanese village.

A powerful graphic memoir, ‘Inside the Giant Fish’ was published by Egypt’s Dar El Mahrousa, and later in English by US-based Maamoul Press, with translation done by illustrator and graphic designer Amy Chiniara.

Issa, who started her career as a journalist, does not produce fictional comics, rather, focuses on documenting real life stories - thus blending between comics journalism and memoirs.

“We know comics are popular through children's books or through heroes, but what I discovered is that comics can also be a journalistic tool. It can be journal, document, and be political,” she said.

Fantasy as an untapped genre

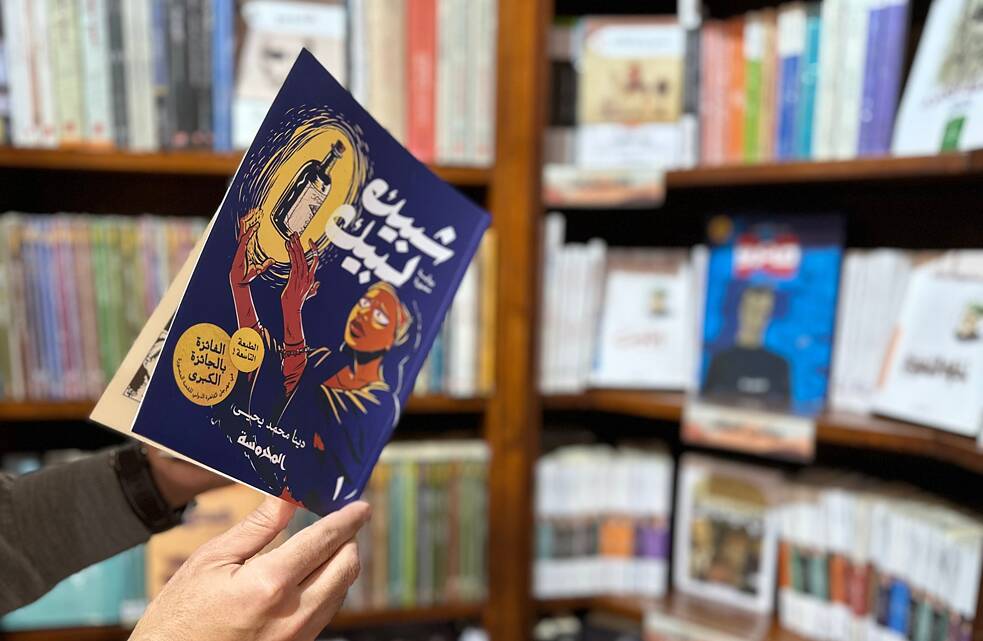

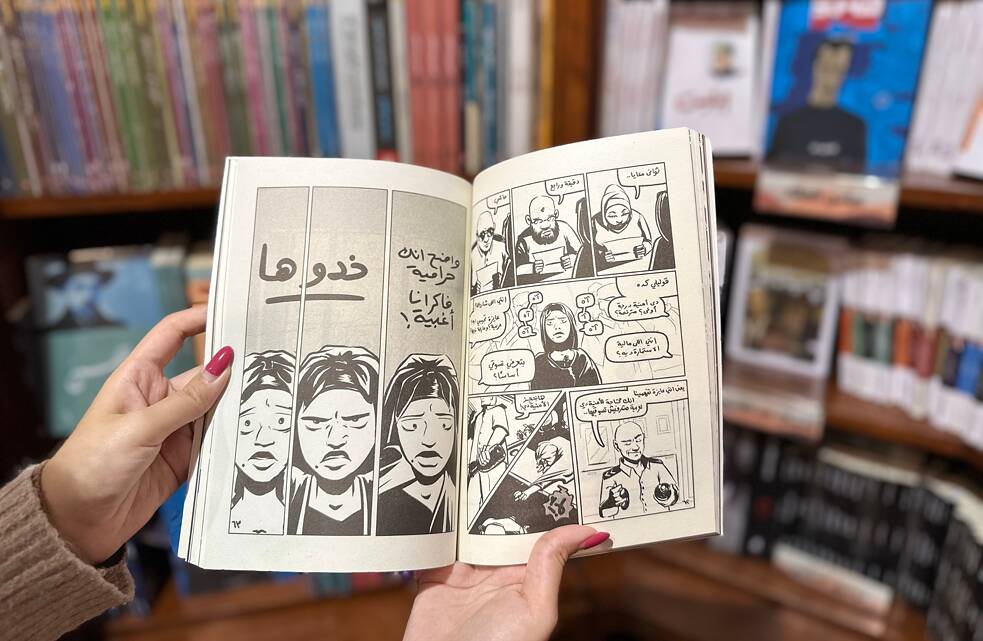

In 2018, Egypt-based Dar El Mahrousa published ‘Shubeik Lubeik’ (Your Wish is My Command), a captivating three-part urban fantasy where wishes are bought and sold in Cairo’s kiosks. It was written, drawn, and translated by Deena Mohamed, an Egyptian comic artist.Mohamed's comic art journey kicked off with a satirical webcomic ‘Qahera’, which addressed misogyny and islamophobia. However, Mohamed did not want to be seen as an activist or a spokesperson for certain issues. Hence, ‘Shubeik Lubeik’ came to life.

“I wanted to tell a fantasy story set in Egypt because I feel like we have a really rich history of fantasy, but a lot of our more popular stories tend to be either comedy or social commentary.”

Drawing from the mundane kiosks of Cairo, Mohamed merges fantasies like flying vehicles, talking animals, and the everlasting magic of wishes with the reality of capitalism, class-based bias, and grief.

“I wanted to do a straightforward fantasy to see if I could work in that genre because that's a genre I enjoy reading,” Mohamed added.

On funding and finances

After self-publishing part one of ‘Shubeik Lubeik’, selling out all 100 copies at CairoComix Festival, Egypt’s first large-scale comics event, and winning Best Graphic Novel and the Grand Prize at the annual festival in 2017, Mohamed was introduced to Dar El Mahrousa, who she believes were “interested in supporting comics in Egypt”.Unfortunately, the comic arts industry is nowhere near lucrative. Most Arab comic artists either depend on a side-job, or struggle to make a living from merely selling their art pieces.

“When I was trying to publish, most publishers … saw no point in publishing a book they couldn't market. They didn't know where to put it and they felt like people wouldn't read it. It was kind of a risk,” Mohamed said.

Mohamed is considered one of the exceptions as she was able to generate income from her art by keeping her translation rights, and selling the translated novel to Pantheon Books in the US and Granta in the UK. But this is not the norm.

For Issa, her experience with publishing houses was not promising.

“When it comes to publishing and dealing with young authors, it's hell in here. Publishers don't really work in favor of authors. If comic artists get more support and funds to publish more, there will be readers,” Issa said.

Similarly, Egyptian comic artist and co-founder of CairoComix Festival, Shennawy, believes comic artists are forced to take up another job to sustain themselves. Having said that, he says this is a struggle for both Arab and European comic artists.

“It's not only Arab comic artists. Even in France, the biggest market for comics in Europe, almost all the artists have to do something else besides publishing comics,” so Shennawy.

To unite comics artists under one roof, together with illustrator Magdy El-Shafee and the Twins Cartoon - the pen name of comic book artists Haitham and Mohamed Raafat El-Seht -

Shennawy co-founded CairoComix Festival in 2015. The annual festival has attracted thousands of visitors, and promotes the works of young Arab comic novelists to a broader audience.

In his experience attending international comic art festivals and exhibitions, Shennawy affirms that, today, people are more aware of the existence of a thriving Arab comic art industry.

CairoComix co-founder Shennawy believes that, today, people are more aware of the existence of a thriving Arab comic art industry | ©egab.co

Arab comics abroad

George Khoury (JAD), artist, critic, and independent researcher in Arabic comic art, echoes Shennawy’s sentiments.As a pioneer of comic art in the Arab world, the Lebanese-born artist published the first graphic novels for adults in Lebanon and across the region in the 1980s. Khoury, influenced by the civil war in Lebanon, created Carnaval, about a young Lebanese man who attempts to escape the war’s atrocities in his country.

“Arab comic art has definitely gained popularity in the region and abroad. This is not wishful thinking, I’ve seen this in my experience,” says Khoury.

Although this art might have received limited support from publishers, the internet and social media played a major role in its widespread and worldwide recognition.

“The Arab comics movement is moving in the right direction, whether the artists can make a living out of it or not is a different story,” Khoury added.

This article was produced in collaboration with Egab.

June 2024