Humanity has always used the arts as a mechanism to document life, preserve cultural memory, and connect people beyond borders by amplifying voices that might otherwise go unheard. Yemen’s artists are therefore gatekeepers to narratives previously unknown, the last frontline between their country and cultural oblivion. What is the role the arts can play in Yemen, and what are the challenges its artists face in pursuing their active roles during the current conflict?

Yemen, a land known for its timeless beauty and rich cultural heritage, has always been famed for its vibrant artistic scene. Artistic Expression is in every Yemeni’s soul, whether passed down from their indigenous tribal ancestry or adapted from the various non-natives that colonized their land. The country’s two main cities, Sana’a and Aden, are cultural hubs in their own rights. In both cities, and furthermore all over the country, a cultural and art scene has thrived for hundreds of years. Its leaders have led revolutions as well as waves of entertainment and they have collectively carried that legacy through the hardest conditions imaginable.Since the Arab Spring, the international media has referred to the Yemeni crisis as the “invisible war,” - but the war is not invisible. The coalition that caused it as well as its facilitators are very visible, and it is experienced every moment of every Yemeni’s life. In the wake of the airstrikes, invaluable cultural heritage sites have been destroyed and Yemen’s social structure has changed forever.

The fallout in a nation’s culture as a consequence of these events is devastating. However, Yemen’s artists and activists have not lost hope. To understand their journey and strife, I had the pleasure of interviewing three artists — both in Yemen and in the diaspora — to cast light on their roles in the cultural scene they are a part of.

ASIM AZIZ: AN AWARD-WINNING FILMMAKER FROM ADEN

Yemeni artists capture the tragedies and hopes of the Yemeni struggle and share them with the world. Advocating for self-expression and succeeding in reaching an international audience, is resident artist, and award-winning filmmaker, Asim Aziz.“Experimental art has no place in Yemen,” Asim says, “but Aden was the perfect place for this kind of art to bloom.”When Asim talks about his art, he credits the city of Aden with being his main inspiration. The coastal city is a historical birthplace of culture and art in the region. Dating back to the 1930s, Aden had the first cinema in The Arabian Peninsula, and a diverse, vibrant scene full of theater troupes, dance groups and poetry collectives. Asim resides in the Kraytar district, situated in the crater of an ancient volcano, and he is surrounded by ancient historic monuments, seemingly of Victorian, Hindu and Islamic origins. Asim compares his life in Aden to living in a museum. With hundreds of years of art influencing him, he was duty-bound to deliver its people’s message. “My art is mainly surrounding psychological issues related to the trauma of the war,” Asim explains, “I speak to people in public transport and on the street about how they face this trauma and the everyday issues they deal with. They are always funny and easy going and emotionally open. If I could,” he says, “I would only bring their stories to life and deliver their small voices to the world.”

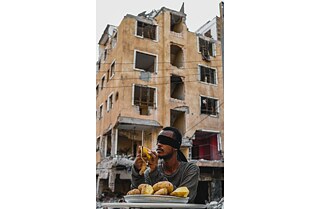

Scene from Asim Aziz film “1941” | ©Asim Aziz

From this openness, Asim’s art was born - a unique expression of emotion and culture. In his short film “1941”, he explores themes of cultural isolation and the desperation for distraction. The short-sighted lives his peers lead are represented in the numbing, knitting pattern the actors carry out throughout the film. The film was funded by the British Council and was the first experimental movie to be produced and shot in Yemen to win international festival awards. Funding was only the first hurdle Asim had to conquer to make his film a reality. “The process involved getting funding, assembling a team, teaching them and training them,” Asim explains, “many people were opposed to making the film because of its experimental nature, and convincing the actors to take their clothes off was another societal norm I had to come head to head with.” The internet and electricity cut-offs were also recurring themes in this experience, as they are in every Yemeni’s life. Another artform that is missing from Yemen is theater. Following the country’s colonization, all cultural centers and theaters were closed and moved to Sana’a, and Aden’s culture suffered a lot from it. Theatre had disappeared almost entirely from Aden’s culture in recent years and the reason for that, Asim explains, is the lack of funding and absence of a proper infrastructure. However, Yemen’s art scene would not flourish if it weren’t for grassroots spaces and individual efforts. Asim’s latest work, as he excitedly informed us, was “Amr Gamal’s Hamlet” for which he served as Director and Production Assistant.

Another independent establishment is Arsheef, a new conceptual gallery based in Sana’a founded by established artist Ibi Ibrahim. In his gallery, Asim was able to showcase his experimental style of photography with “Turning The Light On”, an exhibition that included the works of five emerging Yemeni photographers. Asim relays that this experience gave him solid exposure to exhibiting, something he was able to do a handful of times internationally as well as locally with his latest work being showcased in New York. Asim’s layered approach to storytelling shines through in his photography just as well as it does in his cinematography. He is able to create visuals in his frames that evoke deep emotions of understanding and empathy.

Untitled (2019). Artist: Asim Abdulaziz | ©Asim Abdulaziz

NAJLA ALSHAMI: ART IN THE DIASPORA

Born in Sana’a to a diplomat father, Najla lived most of her early life between Europe and Yemen. She lived in Sana’a until her family was abruptly displaced to Beirut following the outbreak of war in Yemen in 2014. She is currently based in Brussels, where she operates the cultural institution “Yemen Art Base”. When asked about the roots of her activism, Najla explains that her globalized upbringing led her to have a very negative idea of Yemen. The injustices she witnessed directed at the country’s women, led to a visceral reaction that felt like an echo of her ancestors’ oppression and she shouldered the burden of that trauma from a very young age. However, as she embarked on her social justice career in her early adult life, the country’s beauty, its people’s collective oppression, and the part she must play, all became clearer. She says, “Through humanitarian work, I discovered the art hidden in this country’s crevices and I began to crave showing that beauty to the world.”

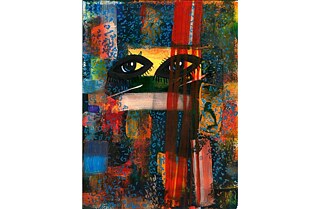

„Unveiling the True Self“. Artist: Najla Alshami | ©Najla Alshami

When asked what it is that the art scene needs the most, Najla explains that access is the key to development. “When I was in Beirut, my art and social life blossomed in a way I could never imagine. Beirut was a hub, a youthful open gate, especially for Yemeni artists, full of community and resources.”, she says, “Yemen has been isolated for a very long time. Up until a few years ago, the artwork there was below average because they couldn’t see where the world had gone to.”

Providing a reliable network and online resources is currently the main objective of “Yemen Art Base”. “I relaunched YAB (Yemen Art Base) while I was in Beirut.” Najla says, “My vision was to create a database that linked all these artists together, but this required a lot of work. Through our “Ya Salam” campaign, we uncovered the vastness of this scene and its potential for a great network where artists would be able to help each other out as well as offer guidance. The next step would be to divide these artists into fractions and analyze their needs.” Funding and permits are always an obstacle, but being based in Europe has its perks. “Being based in Belgium has provided me with many freedoms,” Najla says, “we have more opportunities and exposure so reaching funding is easier than if we were based in Yemen. And if we ever get any trouble from the authorities we can always move the YAB headquarters to Brussels.”

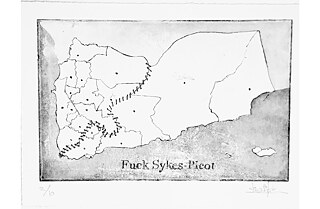

„Fuck Sykes-Picot“ Artist: Najla Alshami | ©Najla Alshami

Unfortunately those privileges are not available for establishments based in Yemen. There is a serious corruption issue within its fundamentally flawed systems. One of the underlying issues with funding in Sana’a is that it is usually dependent on a strict bureaucratic, often European, format. Sometimes it is conditioned by a criteria that involves an alternative agenda which forces artists to alter their vision or even their truth. Funding is often also delegated through local governmental representatives who are supposed to use the money to hire local creatives but end up paying them very little, which will be nothing compared to their worth. Nevertheless, providing spaces and creating a sense of community is a high priority for a lot of artists. One artist working tirelessly on providing that space is Yemeni writer Sadiq Al-Harasi.

SADIQ AL-HARASI: ARCHIVING YEMENI CULTURAL HERITAGE

Sadiq is a program coordinator, writer/storyteller, and visual artist based in Sana’a. Among the projects that Sadiq has led in the past few years is the Romooz Foundation’s literature program “Kitabat” (literary meaning Writings), which has contributed immensely to Yemen’s archive and provided dozens of creatives over its course with online training, workshops and guidance, resulting in the production of tens of literary pieces of all kinds. Through Romooz’s Kitabat, Sadiq has also led “Jalasat”, 10 conversational sessions where writers and content creators came together to discuss their craft, their inspirations and their common struggles. When I spoke to Sadiq and learned of the work he’s been doing, it became quickly obvious that these were projects that were crucial to creating a safe space for other writers to create and learn. However, Sadiq’s main concern is with preserving Yemen’s heritage and social culture.“The Kitabat project closest to my heart has got to be the E-Journal ”, Sadiq says. A grant from the “Prince Claus Foundation” in 2020 made it possible to restore and digitize hundreds of Yemeni cultural magazines from the 80s and 90s. A veritable treasure in the eyes of its archivist and every Yemeni thirsty for a glimpse of what a thriving Yemen looked like.

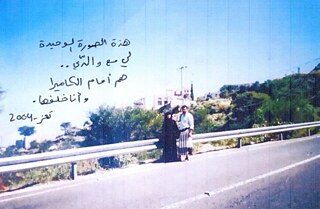

Text on the photo: "This is the only photo of me and my parents. They are in front of the camera, I am behind it." - "Parents Memories" Artist: Sadiq Y. Al-Harasi | ©Sadiq Y. Al-Harasi

Sadiq has also coordinated an archiving project documenting 18 ethnic and tribal folk stories in their original accents. This urge to preserve comes from a very personal place in Sadiq. “I grew up on stories told by my mother and grandfather,” he says, “that is the initial seed from which my imagination grew. But when I think about my younger siblings, I see this sense of wonder is lacking and it’s not their fault. It is an inevitable outcome of the cultural erasure that occurs when your home country is so plagued with turmoil.” When he thinks of that, he is gripped by the fear of his future children suffering a similar fate and is driven to do his best to rectify that outcome. With archiving, he works at preserving these tales and mythical figures so they have a better chance at remaining in the collective consciousness of those future generations. Archiving for Sadiq, however, doesn’t stop in the past. He is keen on documenting and preserving his human experiences through a myriad of mediums and took part in the TA.DH.AM photographic exhibition in Berlin.

Sadiq expresses more of these intimate experiences in his more recent podcast and writing works. As a Yemeni man and creative, expressing negative feelings and speaking out on your issues has always been considered taboo. Sadiq elaborates that his creative process took him to places inside himself that were previously unknown to him. On one of his podcasts, he has one of the most honest conversations he’s ever had with his mother, delving into a painful shared history which they had not discussed for 15 years.

„Where is home?“ Artist: Sadiq Y. Al-Harasi | ©Sadiq Y. Al-Harasi

HOW CAN WE SUPPORT YEMENI ARTISTS?

The devastation of the situation in Yemen, and its artists’ perseverance in the face of it, leave us with so many questions to ask ourselves. How can art continue to thrive in the face of adversity, such as political instability and social turmoil? How would the western world’s artists cope with tragedy and devastation? What would be left? What can these men and women teach us about resilience and clinging to what is important instead of getting swept by everyday anxieties and tragedies?As art lovers and global citizens, it is our responsibility to do what we can to support and promote the Yemeni art scene. Whether it's through attending exhibitions, purchasing artwork, or spreading awareness through social media, we can all play a role in helping to preserve and celebrate Yemen's ancient cultural vortex, and prevent it from disappearing into a void of forgetfulness.

This article was sponsored by the Goethe-Institut Amman as part of the “Cultural Networks Yemen” project with the support of the German Federal Foreign Office, and was also supported by the EU-funded project Yemen Creative Hubs. Both projects empower Yemeni artists and those responsible for the cultural sector by offering training, mentoring programs and funding opportunities for their projects.

July 2024