Stillness in Modern Dance

The Power of that Textured Repose

A few short weeks ago, few among us would have ever imagined the world to be in this place. Awakening to the crisis in Ukraine, we are seeing the ache of despair and sorrow. Our narrowly sidestepping nuclear catastrophe keeps us tethered to the principle of liminality.

No one is sure about the magnitude of what’s ahead, but surely as we witness a tide of humanity walking across borders, we also see the body in confinement, outside of transitory freedom, trapped, unable to leave or move. It’s a profoundly sad and traumatic realization of standstill.

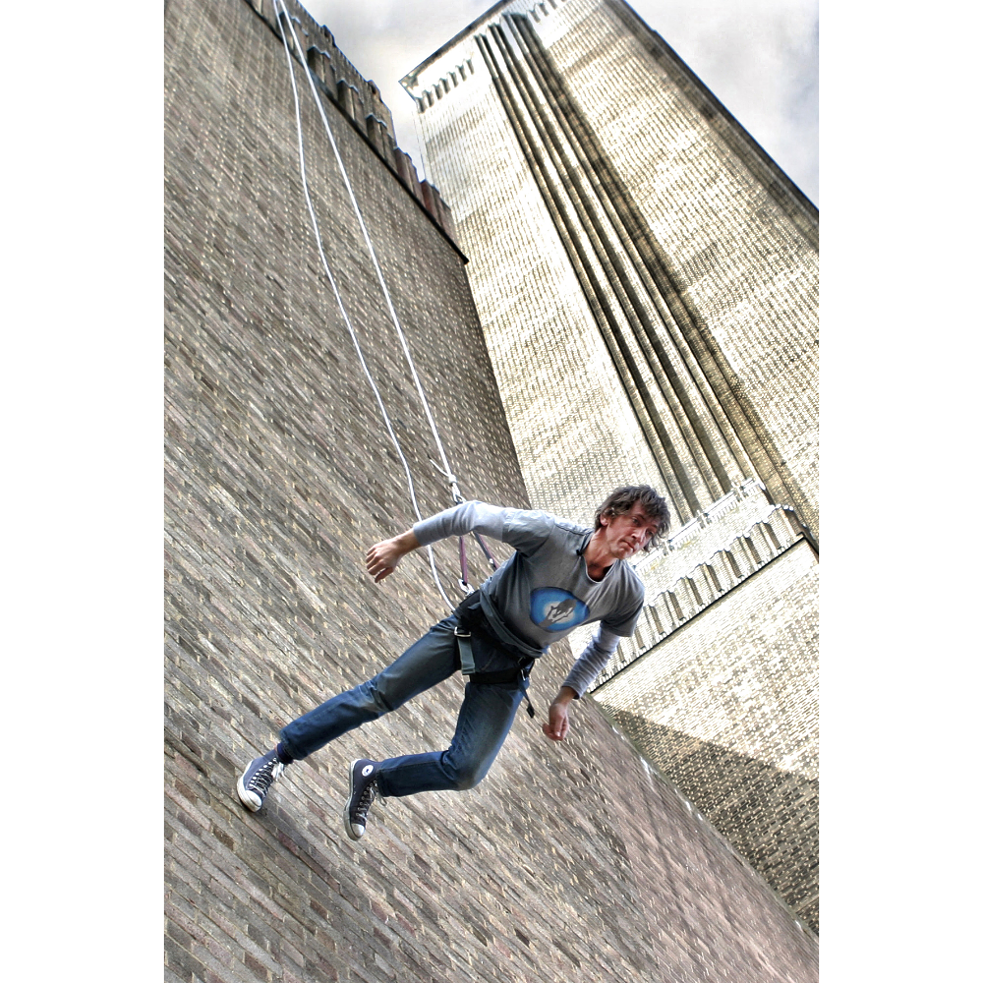

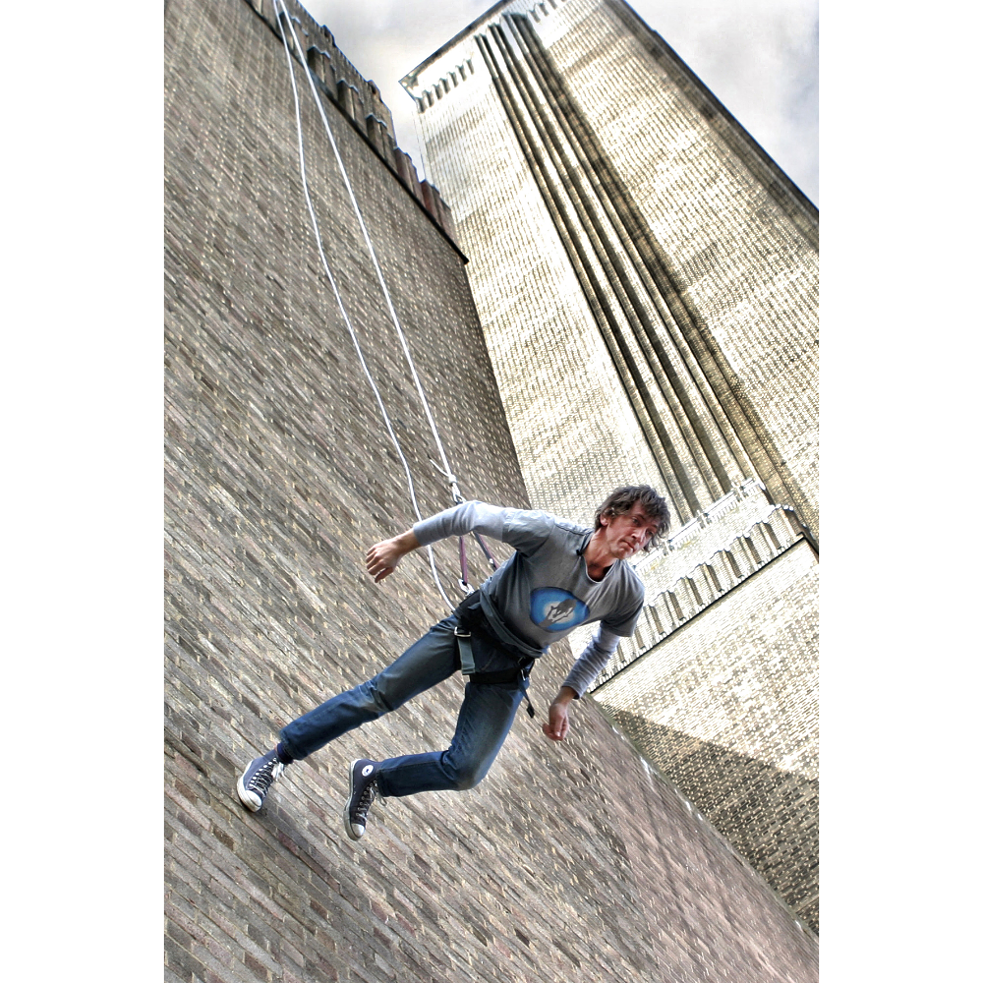

In the 1960s, post-World War II, America was busy being reborn. It was a time where choreographer and dancer Trisha Brown took a radical approach to the human body. In Brown’s conception of the seemingly death-defying stroll in Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), we see an artist making space into place. In Lower Manhattan, a man, her then husband, made his descent, suspended horizontally by a harness rigged on cables, walking across seven stories of an exterior wall of a building. At the heart of this piece, Brown was creating a liminal space, enacted outside — and often in contradistinction to — the control of institutional authority. She chose to resituate navigation and place, altering the paradigm of what dance and performative mobility could be.

Trisha Brown Dance Company’s “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” (1971) performed on Tate Modern during the UBS Openings: the long weekend of Monday, May 28th, 2006

| © Trisha Brown Dance Company, Photo © Sheila Burnett, courtesy of Tate Images.

The shift was emblematic of the New York downtown dance scene challenging convention in dance and the rigid function of theatrical dance. The Building piece was propelled not by the usual structures of dance composition but by the inventive quality of Brown’s inquiry: the risky way in which she created an enigmatic and singular zone of in-between and a transitory engagement of space. The experience of distortion — even fear — lived by the performer and by the spectator link risk and physical endurance to feelings of awe in the communal experience of this extraordinary work.

Trisha Brown Dance Company’s “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” (1971) performed on Tate Modern during the UBS Openings: the long weekend of Monday, May 28th, 2006

| © Trisha Brown Dance Company, Photo © Sheila Burnett, courtesy of Tate Images.

The shift was emblematic of the New York downtown dance scene challenging convention in dance and the rigid function of theatrical dance. The Building piece was propelled not by the usual structures of dance composition but by the inventive quality of Brown’s inquiry: the risky way in which she created an enigmatic and singular zone of in-between and a transitory engagement of space. The experience of distortion — even fear — lived by the performer and by the spectator link risk and physical endurance to feelings of awe in the communal experience of this extraordinary work.

Students in a Gaga class

| © Ascaf

Engaging in the Gaga reflex, dancers (re)experience the joy of dancing and the power of dance, he says, by creating new possibilities that will affect their virtuosity and their creativity. Something significant happens to the dancers’ capabilities as Gaga works on sensory awareness, coordination, and sensitivities. The dancer is strong and loose at the same time. Gaga taps into stretching, over- and under-exaggeration, high and low volume and affects suppleness, agility, movement efficiency, intentionality, and clarity. It’s about connecting to weaknesses, physical fixations, and what each one of us adheres to unconsciously. “It’s about giving yourself over to the movement and the connection between passion, effort, pain and pleasure, sexuality and sublimation,” Naharin says. Gaga is about overlapping and multilayering tasks, building on ideas. It is a fundamentally intimate place of reorientation that can stoke the sensation of calm, nurturing a stillness — in essence, giving permission to forego the frenzy of our lives and inhabit an inner quietness. “It’s the opposite of blocking,” he says. “Forcing things, people get sick, and we have to heal ourselves.” He relates it to groove. “Groove is not always music. It is also a vibe. Gaga makes the bones vibrate.”

Students in a Gaga class

| © Ascaf

Engaging in the Gaga reflex, dancers (re)experience the joy of dancing and the power of dance, he says, by creating new possibilities that will affect their virtuosity and their creativity. Something significant happens to the dancers’ capabilities as Gaga works on sensory awareness, coordination, and sensitivities. The dancer is strong and loose at the same time. Gaga taps into stretching, over- and under-exaggeration, high and low volume and affects suppleness, agility, movement efficiency, intentionality, and clarity. It’s about connecting to weaknesses, physical fixations, and what each one of us adheres to unconsciously. “It’s about giving yourself over to the movement and the connection between passion, effort, pain and pleasure, sexuality and sublimation,” Naharin says. Gaga is about overlapping and multilayering tasks, building on ideas. It is a fundamentally intimate place of reorientation that can stoke the sensation of calm, nurturing a stillness — in essence, giving permission to forego the frenzy of our lives and inhabit an inner quietness. “It’s the opposite of blocking,” he says. “Forcing things, people get sick, and we have to heal ourselves.” He relates it to groove. “Groove is not always music. It is also a vibe. Gaga makes the bones vibrate.”

The so-called “standing man” of the Taksim Square, Erdem Gündüz takes part in the performance project “Verhaltet Euch ruhig” (“Stay Calm”) at the Kesselhaus arts venue in Berlin, Germany, on October 26, 2014. The format of the project showcases methods that connect civil non-violent resistance, art, and the possibilities of participation and spectatorship.

| Jörg Carstensen © picture alliance / dpa

The stance emphasizes strength, control, and concentration and an underlying internal pilgrimage. It speaks to a space of transition, not hermetic limbo, and a movement towards a liberated state of being and a divine light contained within. Even Samuel Beckett, sometimes called the bard of inertia, might have approved. In 2013, Turkish dance artist Erdem Gündüz espoused a similar posture with his Standing Man performance, becoming an icon of the silent, peaceful, still protest. He’s even become his own meme, as “standing man” (“duran adam,” in Turkish). His activism didn’t involve throwing stones or shouting slogans, he just stood motionless in the middle of Istanbul’s Taksim Square for hours staring at the portrait of the founder of the modern Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, protesting for freedom of expression and against police brutality.

The so-called “standing man” of the Taksim Square, Erdem Gündüz takes part in the performance project “Verhaltet Euch ruhig” (“Stay Calm”) at the Kesselhaus arts venue in Berlin, Germany, on October 26, 2014. The format of the project showcases methods that connect civil non-violent resistance, art, and the possibilities of participation and spectatorship.

| Jörg Carstensen © picture alliance / dpa

The stance emphasizes strength, control, and concentration and an underlying internal pilgrimage. It speaks to a space of transition, not hermetic limbo, and a movement towards a liberated state of being and a divine light contained within. Even Samuel Beckett, sometimes called the bard of inertia, might have approved. In 2013, Turkish dance artist Erdem Gündüz espoused a similar posture with his Standing Man performance, becoming an icon of the silent, peaceful, still protest. He’s even become his own meme, as “standing man” (“duran adam,” in Turkish). His activism didn’t involve throwing stones or shouting slogans, he just stood motionless in the middle of Istanbul’s Taksim Square for hours staring at the portrait of the founder of the modern Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, protesting for freedom of expression and against police brutality.

We can’t necessarily diminish the threats we face. Our task throughout our present-day challenges in which the histories of the body, trauma, and emotion overlap must be to fundamentally make meaning by way of our creative work or, alternately, in the microcosm of our simplest actions. What this moment in time has allowed us is to slow down, listen, and resonate with the power of that textured repose, observing the quietude and renewal that affords the possibility of transformation.

A Moment of Stillness

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic — when many of us were socially distanced armchair adventurers, and everything was forced to shut down — so much was unknown. Fear was rampant and isolation was everything. In that moment, apparently, Google searches for the words “liminal,” “liminality,” and “liminal spaces” began to surge. Anthropologists Victor and Edith Turner describe this rite of passage and the threshold as a modality where the ordinary rules of day-to-day demands cannot intervene. It’s a “breathe in, breathe out” moment for reflection, a moment of stillness. Perhaps above all, it is a moment where there is a suspension of time. In this frame, I am brought to consider examples of dance artists who, in their tribulations, have moved into that in-between place, offering an aspirational meeting space for exploration and discovery.In the 1960s, post-World War II, America was busy being reborn. It was a time where choreographer and dancer Trisha Brown took a radical approach to the human body. In Brown’s conception of the seemingly death-defying stroll in Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), we see an artist making space into place. In Lower Manhattan, a man, her then husband, made his descent, suspended horizontally by a harness rigged on cables, walking across seven stories of an exterior wall of a building. At the heart of this piece, Brown was creating a liminal space, enacted outside — and often in contradistinction to — the control of institutional authority. She chose to resituate navigation and place, altering the paradigm of what dance and performative mobility could be.

Trisha Brown Dance Company’s “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” (1971) performed on Tate Modern during the UBS Openings: the long weekend of Monday, May 28th, 2006

| © Trisha Brown Dance Company, Photo © Sheila Burnett, courtesy of Tate Images.

The shift was emblematic of the New York downtown dance scene challenging convention in dance and the rigid function of theatrical dance. The Building piece was propelled not by the usual structures of dance composition but by the inventive quality of Brown’s inquiry: the risky way in which she created an enigmatic and singular zone of in-between and a transitory engagement of space. The experience of distortion — even fear — lived by the performer and by the spectator link risk and physical endurance to feelings of awe in the communal experience of this extraordinary work.

Trisha Brown Dance Company’s “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” (1971) performed on Tate Modern during the UBS Openings: the long weekend of Monday, May 28th, 2006

| © Trisha Brown Dance Company, Photo © Sheila Burnett, courtesy of Tate Images.

The shift was emblematic of the New York downtown dance scene challenging convention in dance and the rigid function of theatrical dance. The Building piece was propelled not by the usual structures of dance composition but by the inventive quality of Brown’s inquiry: the risky way in which she created an enigmatic and singular zone of in-between and a transitory engagement of space. The experience of distortion — even fear — lived by the performer and by the spectator link risk and physical endurance to feelings of awe in the communal experience of this extraordinary work.

“Don’t Say No”

Changing the mind-body dynamic and offering a new kind of engagement with the world is also richly linked to Ohad Naharin’s self-devised movement language called “Gaga,” which any dancer he’s working with trains with daily. It’s a creative system in which playful uber-feelings burble to the surface, helping dancers (and non-dancers) understand their movement habits, their places of atrophy. This enables new explorations of moving and, ultimately, being. But this meaningful connection is also a powerful liminal space where nothing, especially social structure, interferes with or impedes the pause at a profound level, leading to a heightened understanding of the vastness of being still. A key element in grasping the Gaga ideal, as Naharin told me in an interview some years ago, is to harness negativity. “Don’t say no,” he stated emphatically. Students in a Gaga class

| © Ascaf

Engaging in the Gaga reflex, dancers (re)experience the joy of dancing and the power of dance, he says, by creating new possibilities that will affect their virtuosity and their creativity. Something significant happens to the dancers’ capabilities as Gaga works on sensory awareness, coordination, and sensitivities. The dancer is strong and loose at the same time. Gaga taps into stretching, over- and under-exaggeration, high and low volume and affects suppleness, agility, movement efficiency, intentionality, and clarity. It’s about connecting to weaknesses, physical fixations, and what each one of us adheres to unconsciously. “It’s about giving yourself over to the movement and the connection between passion, effort, pain and pleasure, sexuality and sublimation,” Naharin says. Gaga is about overlapping and multilayering tasks, building on ideas. It is a fundamentally intimate place of reorientation that can stoke the sensation of calm, nurturing a stillness — in essence, giving permission to forego the frenzy of our lives and inhabit an inner quietness. “It’s the opposite of blocking,” he says. “Forcing things, people get sick, and we have to heal ourselves.” He relates it to groove. “Groove is not always music. It is also a vibe. Gaga makes the bones vibrate.”

Students in a Gaga class

| © Ascaf

Engaging in the Gaga reflex, dancers (re)experience the joy of dancing and the power of dance, he says, by creating new possibilities that will affect their virtuosity and their creativity. Something significant happens to the dancers’ capabilities as Gaga works on sensory awareness, coordination, and sensitivities. The dancer is strong and loose at the same time. Gaga taps into stretching, over- and under-exaggeration, high and low volume and affects suppleness, agility, movement efficiency, intentionality, and clarity. It’s about connecting to weaknesses, physical fixations, and what each one of us adheres to unconsciously. “It’s about giving yourself over to the movement and the connection between passion, effort, pain and pleasure, sexuality and sublimation,” Naharin says. Gaga is about overlapping and multilayering tasks, building on ideas. It is a fundamentally intimate place of reorientation that can stoke the sensation of calm, nurturing a stillness — in essence, giving permission to forego the frenzy of our lives and inhabit an inner quietness. “It’s the opposite of blocking,” he says. “Forcing things, people get sick, and we have to heal ourselves.” He relates it to groove. “Groove is not always music. It is also a vibe. Gaga makes the bones vibrate.”

The Possibility of Transformation

There’s a foundational idea that dance serves as a catalyst of transformation. In Lin Hwai-min’s Songs of the Wanderers (1994) from Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, we witness a monk in white robes standing motionless on stage for 70 minutes under a steady stream of falling rice. The so-called “standing man” of the Taksim Square, Erdem Gündüz takes part in the performance project “Verhaltet Euch ruhig” (“Stay Calm”) at the Kesselhaus arts venue in Berlin, Germany, on October 26, 2014. The format of the project showcases methods that connect civil non-violent resistance, art, and the possibilities of participation and spectatorship.

| Jörg Carstensen © picture alliance / dpa

The stance emphasizes strength, control, and concentration and an underlying internal pilgrimage. It speaks to a space of transition, not hermetic limbo, and a movement towards a liberated state of being and a divine light contained within. Even Samuel Beckett, sometimes called the bard of inertia, might have approved. In 2013, Turkish dance artist Erdem Gündüz espoused a similar posture with his Standing Man performance, becoming an icon of the silent, peaceful, still protest. He’s even become his own meme, as “standing man” (“duran adam,” in Turkish). His activism didn’t involve throwing stones or shouting slogans, he just stood motionless in the middle of Istanbul’s Taksim Square for hours staring at the portrait of the founder of the modern Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, protesting for freedom of expression and against police brutality.

The so-called “standing man” of the Taksim Square, Erdem Gündüz takes part in the performance project “Verhaltet Euch ruhig” (“Stay Calm”) at the Kesselhaus arts venue in Berlin, Germany, on October 26, 2014. The format of the project showcases methods that connect civil non-violent resistance, art, and the possibilities of participation and spectatorship.

| Jörg Carstensen © picture alliance / dpa

The stance emphasizes strength, control, and concentration and an underlying internal pilgrimage. It speaks to a space of transition, not hermetic limbo, and a movement towards a liberated state of being and a divine light contained within. Even Samuel Beckett, sometimes called the bard of inertia, might have approved. In 2013, Turkish dance artist Erdem Gündüz espoused a similar posture with his Standing Man performance, becoming an icon of the silent, peaceful, still protest. He’s even become his own meme, as “standing man” (“duran adam,” in Turkish). His activism didn’t involve throwing stones or shouting slogans, he just stood motionless in the middle of Istanbul’s Taksim Square for hours staring at the portrait of the founder of the modern Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, protesting for freedom of expression and against police brutality.We can’t necessarily diminish the threats we face. Our task throughout our present-day challenges in which the histories of the body, trauma, and emotion overlap must be to fundamentally make meaning by way of our creative work or, alternately, in the microcosm of our simplest actions. What this moment in time has allowed us is to slow down, listen, and resonate with the power of that textured repose, observing the quietude and renewal that affords the possibility of transformation.