A conversation with Yewande Pearse

Engaging the Senses for Science Communication

Yewande Pearse is a neuroscientist and science communicator. Upon invitation by the Goethe-Institut Montreal, she participated in „New Nature“, an immersive media and climate science exchange. After the event, we had the opportunity to talk to Yewande in more detail about her fascination with the brain, her podcast, and what different sensory experiences bring to science communication.

Von Janna Frenzel

Dr. Yewande Pearse, thank you for taking the time to talk more about some of the themes of New Nature and your own work. How did you become fascinated with the brain, and what brought you to your specific focus within neuroscience?

The way I describe it is that I worked my way up from the feet and ended up in the brain. I did my undergraduate studies in Human Biology at King’s College London. In my final year, I took courses on mechanisms of development and neurology. It wasn’t like I hadn’t thought about the brain before but learning about how it develops just completely blew my mind! It is fascinating how this incredibly complex organ works.

Typical for academia, my field became more and more niche the more I specialized. My focus is now on neurodegenerative diseases, and specifically rare diseases that affect children. I ended up working on a disease called Sanfilippo syndrome. It belongs to a group of diseases called “lysosomal storage disorders” that result from single genetic mutations that mess with the waste disposal system in cells, resulting in waste material building up. Even though the focus of my research is pretty niche, it has always been important to me to study things that can be applied to lots of different brain diseases. During my PhD, I became interested in gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and gene editing, which you can apply in a lot of different areas such as Alzheimer’s disease or Huntington’s disease. In the end, I’m just really interested in what happens when the brain goes wrong and what we can do to try and fix it!

In your view, what can a neuroscience perspective bring to the conversation about human-environment relations that was central to New Nature?

When I was initially invited, I have to admit I was scratching my head about what neuroscience can bring to this conversation, apart from the fact that neuroscience and stem cell research contributes to some of causes of climate change, such as high energy consumption, and therefore a high carbon footprint. I’ve often thought about this when using single-use plastics at work, which you have to use because everything needs to be sterile. I have the impression that science gets a pass when it comes to its implication in climate change, because it is justified as being for the greater good. To cure a childhood brain disease, you have to do what you have to do, right? But then I started to think beyond this and reflect on how science can act more responsibly and address its contribution to climate change outside of a framework that posits that the benefits of research outweigh the environmental costs.

By participating in New Nature, I realized however that maybe that is not the most important aspect of neuroscience’s potential role in the conversation. A few of the discussions that really stuck with me were the ones around mycelium [vegetative body for fungi that produce mushrooms, ed.] and how certain mechanisms in nature are mirrored in the brain, for example when you compare mycelium networks and neural networks. I also see a lot of potential in Virtual Reality (VR) and how it can be used to tour a number of different biological networks, to investigate the similarities between the design of the brain and the design of other systems in nature.

On one episode of my podcast, Sound Science, I talked to artist and ecologist Jana Winderen about what capturing nature's hidden language through sound can tell us about the environment. What I really liked about speaking to her was that they pointed out how empathizing with nature through sound makes one more aware and more conscious of how we are a part of nature. Nature isn’t there to just serve us. We are not at the center of it - it has its own thing going on. Maybe by exploring connectivity between the development of the human body, the brain and the environment, we can achieve a similar sort of empathy through identifying commonalities.

Speaking of "Sound Science", how did you develop the idea for your podcast?

I have a strong interest in science interpretation and communication and was looking for new ways to communicate complex ideas. I was very inspired by other podcasts like Hidden Brain and Invisibilia, and the opportunity to host a podcast came up because I had a platform, Dublab Radio, that liked my idea.

The podcast brings together two things I’m passionate about: science and music. I wanted to explore what understandings of science and music I can share with my audience, particularly with people who love music and sound but might not even have thought about the science side of it. My aim was to invite people who like music into science and people who like science into music. And through sound, create a new avenue for learning about science that is fun and breaks the distance and inaccessibility often associated with it.

Besides bridging the worlds of science and music, the podcast is a great way for me to keep learning about the brain as a whole. Like I said before, neuroscience can become quite niche, and it’s easy to lose track of the big picture. The podcast gives me the opportunity to look beyond what I am currently researching in the lab and explore topics as diverse as consciousness, psychedelics, or grief, together with amazing guests.

What has your experience been like as a podcast host?

What’s been most interesting about the process of podcasting on a personal level is that it opened me up to the idea that you can teach yourself a lot of things with no formal training—I really surprised myself that I could put a podcast together! The tools that are available are amazing, and you can figure it out pretty much on your own.

In terms of topics, I thought the first episode was very powerful, which was about the science of heartbreak and why it feels like physical pain. It was really fascinating to learn how the brain gets confused between the two. The scientific explanation validates something that you already know when you feel it, which I think is really cool. Everyone knows how painful that emotion is and can relate to it. But understanding the neuroscience behind it puts it into new light. The Sounds of Nature-episode that I presented at New Nature was definitely a highlight too. I also did one about Endel, which is an AI-based app that generates reactive, personalized soundscapes that respond to your personal needs.

One thing I find challenging about hosting a science podcast is that as a scientist, I have the responsibility to make sure that the information I’m sharing is peer-reviewed. The podcast is a venue for digging deeper into the science behind a claim or an observation. For example, in Episode 5, titled “The Left-brain vs. the Right-brain”, I spoke to Dr. Rex Jung, Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of New Mexico about the long-held belief that people have either a left or right-brained style of thinking and that creative types like musicians fall into the latter group. In the episode, we discuss why it’s not quite that simple

At New Nature, we talked a lot about new ways to understand the world through storytelling and listening on the one hand, and through immersion and experience on the other. Do you see these two approaches as complementary or different pathways for learning?

VR and sound-based work engage different senses. Both are very powerful on their own, but together, would constitute what is referred to as a multisensory approach to learning - visual and auditory. Many studies on learning and memory focus on just a single sensory modality, but in real life, we are constantly exposed to multisensory stimulation. Our senses are constantly engaged. Therefore, it makes sense that our brains would have evolved to learn optimally in such an environment, and that utilizing tools like VR and sound to facilitate learning would be a great idea. Context is important of course, but, a paper in Nature Neuroscience published earlier this year for example suggests that multisensory learning could potentially empower cognitive development from childhood.

I have to say, this study and similar studies focus on visual stimuli like 2D images. I cannot speak much about VR specifically, but I have come across one study from a couple of years ago, in which scientists looked at whether immersive and interactive VR improves learning and retention of neuroanatomy in medical students and found that it may be an effective learning tool, but a lot more study is needed. Personally, I’m really interested in how VR could be applied as a research tool, for example for touring the brain. For instance, the way we visualise data can be quite dry. Right now for example, I am looking at complex networks of genes that are disregulated in brain organoid models of Alzheimer’s disease. Visualizing data sets in this way can be hard to digest. I wonder how the research process would change if we were able to navigate through our models using VR.

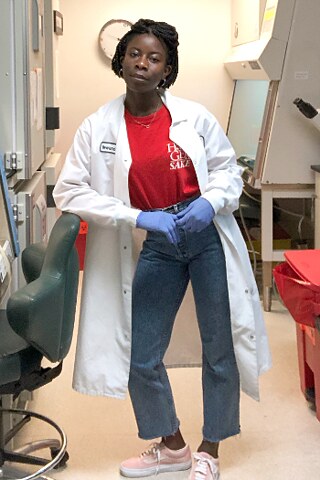

Dr. Yewande Pearse

Dr. Yewande Pearse is a neuroscientist and science communicator. Her research interests in the lab focus on brain pathologies and their potential treatments, but her fascination with the brain is not limited to any one area of the field. She gained her Ph.D. from King’s College London and is a Postdoctoral Fellow at The Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA, in affiliation with UCLA. Outside of the lab, Yewande hosts a music/science podcast on Dublab radio called Sound Science, has written for Massive Science and TEDMED and is a member of the Collective Residency at NAVEL Los Angeles, where she served on the 2019 Programming Committee and is a member of the Board of Directors.