City contours: Frankfurt

From soaring skyline to down-to-earth graffiti

Frankfurt does not enjoy the best reputation and is known for its banking district, major international airport, drug scene, and red-light district. And while few would choose the city as their new home, most people who move to Frankfurt soon discover they never want to leave. Our author Eva-Maria Verfürth goes beyond the clichés to show what makes Germany’s financial hub so liveable and lovable.

By Eva-Maria Verfürth

Skyline and housing battle

Frankfurt’s skyline is the city’s hallmark.

| Photo (detail): © Adobe

While it might not impress anyone from the US, Frankfurt’s skyline is unique in Germany. Of the 18 skyscrapers in the country, 17 are in Frankfurt, and more than 30 buildings tower over 100 metres tall. The towers of glass and steel offer office space primarily to banks, insurance companies and consulting firms, which is why the streets between the opera house and the central train station are known as “the banking district”. It emerged right after the Second World War when Germany’s financial hub shifted from Berlin to Frankfurt and the city, which is now home to 300 domestic and international banks, became one of Europe’s most important financial hubs. The only reason the city does not have even more concrete giants occupying the sites of older buildings is because Frankfurt’s residents rose up in opposition. In the 1970s, they came together in large demonstrations to protest the displacement of tenants from Frankfurt’s Westend and occupied historical buildings to keep them from being razed. This led to violent clashes with police and the grassroots opposition movement went down in history as “Frankfurt’s housing battle”. It succeeded in saving many historical buildings, and skyscraper construction, which boomed in the 1980s and 1990s, was limited to just a few city blocks. Protesters were less successful though in solving the underlying problems that fuelled their outrage: real estate speculation, gentrification and renter displacement are still huge issues for the city today.

Frankfurt’s skyline is the city’s hallmark.

| Photo (detail): © Adobe

While it might not impress anyone from the US, Frankfurt’s skyline is unique in Germany. Of the 18 skyscrapers in the country, 17 are in Frankfurt, and more than 30 buildings tower over 100 metres tall. The towers of glass and steel offer office space primarily to banks, insurance companies and consulting firms, which is why the streets between the opera house and the central train station are known as “the banking district”. It emerged right after the Second World War when Germany’s financial hub shifted from Berlin to Frankfurt and the city, which is now home to 300 domestic and international banks, became one of Europe’s most important financial hubs. The only reason the city does not have even more concrete giants occupying the sites of older buildings is because Frankfurt’s residents rose up in opposition. In the 1970s, they came together in large demonstrations to protest the displacement of tenants from Frankfurt’s Westend and occupied historical buildings to keep them from being razed. This led to violent clashes with police and the grassroots opposition movement went down in history as “Frankfurt’s housing battle”. It succeeded in saving many historical buildings, and skyscraper construction, which boomed in the 1980s and 1990s, was limited to just a few city blocks. Protesters were less successful though in solving the underlying problems that fuelled their outrage: real estate speculation, gentrification and renter displacement are still huge issues for the city today.

Clubbing in the red-light district

Restaurants and in-clubs on the ground floor with red lights above: the Bahnshofsviertel around central station attracts people with very different interests.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / dpa / Boris Roessler

The area around the central station, the Bahnhofsviertel, has been a major contributor to the city’s bad reputation. Here in the shadows cast by the gleaming bank towers is the city’s darker underbelly, the red-light district with dive bars and a methadone dispensary. Exit on the wrong side of central station and you’ll find yourself pushing your way through addicts waiting for their next fix. This once upscale neighbourhood was built around the turn of the last century based on the Parisian model, but it has gone considerably downhill since then. But the area has another side that has made it one of the city’s most iconic in-spots in recent years: it is also where Frankfurt shows off its international flair with Indian supermarkets, Persian snack bars, Pakistani kiosks, Ethiopian restaurants and German corner pubs all in close-quartered harmony. Hipster bars and electro clubs have also made inroads. It is worth making at least one round to experience the old Bahnhofsviertel flair at Moseleck, where you can strike up a bizarre conversation with a stranger at any time of day or night, its new spirit at the Yok Yok kiosk, where the party crowd meets up to grab a kiosk beer in the evening. Put on your dancing shoes for the house music at Planck or Pracht, enjoy cabaret among red-velvet plush furnishings at Pik Dame, once a striptease club, or travel back to the roaring 20s at Orange Peel.

Restaurants and in-clubs on the ground floor with red lights above: the Bahnshofsviertel around central station attracts people with very different interests.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / dpa / Boris Roessler

The area around the central station, the Bahnhofsviertel, has been a major contributor to the city’s bad reputation. Here in the shadows cast by the gleaming bank towers is the city’s darker underbelly, the red-light district with dive bars and a methadone dispensary. Exit on the wrong side of central station and you’ll find yourself pushing your way through addicts waiting for their next fix. This once upscale neighbourhood was built around the turn of the last century based on the Parisian model, but it has gone considerably downhill since then. But the area has another side that has made it one of the city’s most iconic in-spots in recent years: it is also where Frankfurt shows off its international flair with Indian supermarkets, Persian snack bars, Pakistani kiosks, Ethiopian restaurants and German corner pubs all in close-quartered harmony. Hipster bars and electro clubs have also made inroads. It is worth making at least one round to experience the old Bahnhofsviertel flair at Moseleck, where you can strike up a bizarre conversation with a stranger at any time of day or night, its new spirit at the Yok Yok kiosk, where the party crowd meets up to grab a kiosk beer in the evening. Put on your dancing shoes for the house music at Planck or Pracht, enjoy cabaret among red-velvet plush furnishings at Pik Dame, once a striptease club, or travel back to the roaring 20s at Orange Peel.

Stroll through the hip parts of town

Frankfurt’s inner city is very green with only the tops of the towers in the distance as a reminder of its status as a key financial hub.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / J.W. Alker

With a population of around 750,000, Frankfurt is exceptionally small for such an internationally important centre of finance. This means you can enjoy everything that makes big city life so exciting, just with less travel and a bit less rowdy than in the million-plus cities. Outside of the gleaming banking district, not large square-metrewise, Frankfurt is characterized by playful Wilhelminian architecture and generous parks. The inner-city residential districts of Bornheim, Nordend, Bockenheim and Sachsenhausen are attractive for their quiet side streets, cosy cafes and restaurants, pretty boutiques, wild art-house cinemas and quaint bookstores. Every neighbourhood has its own High Street and the longest – Berger Strasse – stretches for almost three kilometres from downtown to the old village centre with half-timbered houses and onion-domed church. Even the small retail trade survives here from the small, corner art supply shop to the family-run hardware store on the square. It is punctuated by a lot of green: picturesque Bethmann Park with its Chinese garden, Günthersburg Park with a lawn for sunbathers and open-air concerts, the garden around Holzhausen Palace, spacious and winding Grüneburg Park and wild Ost Park. You won’t find a lot of suit-wearing, briefcase carriers here and the top of a glass tower is only occasionally visible at the end of a colourful street of old buildings or just above the treetops in the park, as a small reminder of the banking world that seems so very far away.

Frankfurt’s inner city is very green with only the tops of the towers in the distance as a reminder of its status as a key financial hub.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / J.W. Alker

With a population of around 750,000, Frankfurt is exceptionally small for such an internationally important centre of finance. This means you can enjoy everything that makes big city life so exciting, just with less travel and a bit less rowdy than in the million-plus cities. Outside of the gleaming banking district, not large square-metrewise, Frankfurt is characterized by playful Wilhelminian architecture and generous parks. The inner-city residential districts of Bornheim, Nordend, Bockenheim and Sachsenhausen are attractive for their quiet side streets, cosy cafes and restaurants, pretty boutiques, wild art-house cinemas and quaint bookstores. Every neighbourhood has its own High Street and the longest – Berger Strasse – stretches for almost three kilometres from downtown to the old village centre with half-timbered houses and onion-domed church. Even the small retail trade survives here from the small, corner art supply shop to the family-run hardware store on the square. It is punctuated by a lot of green: picturesque Bethmann Park with its Chinese garden, Günthersburg Park with a lawn for sunbathers and open-air concerts, the garden around Holzhausen Palace, spacious and winding Grüneburg Park and wild Ost Park. You won’t find a lot of suit-wearing, briefcase carriers here and the top of a glass tower is only occasionally visible at the end of a colourful street of old buildings or just above the treetops in the park, as a small reminder of the banking world that seems so very far away.

Driving license for the lift

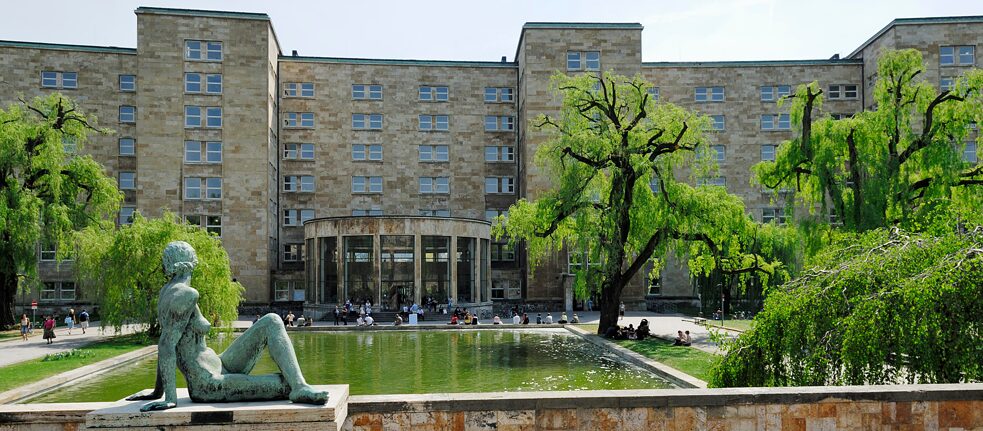

Initially a company headquarters, then a military base: the historic Johann Wolfgang von Goethe University campus has a long and varied history.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / imageBROKER / Stefan Espenhahn

There are only about 250 left in all of Germany, and very few are open to the public, but they are still up and running in Frankfurt: the paternosters, the nostalgic passenger elevators from the turn of the last century. Since health and safety forced the switch to closed lifts in the 1970s, these moving wooden boxes have become a rarity. Yet they are so much more fun to get – or more accurately hop – on and off of, which you can discover in the no fewer than eight chains of open boxes ceaselessly rotating in Frankfurt’s Goethe University central building. In the past, they were only open to university employees who had passed a special instruction course in the art of riding a paternoster and were monitored by specially hired security personnel. They are now open to the general public again though. The imposing architecture of the main university building that surrounds the clattering lifts is worth a look as well. Built around 1930 as the headquarters of chemical and pharmaceutical giant I.G. Farben, the 250-metre-long building is a memorial to a dark past, given that the company was involved in the distribution of the Zyklon B used in the gas chambers under the National Socialist regime and also operated its own concentration camp. Following the war, the US initially used it as a military base. Today the university is housed here, filling the space with more positive and peaceful energy. It is palpable in the huge linden trees and weeping willows growing in the historic greenspaces around the central building where small stone walls crisscross the meadows, a nymph sculpture adorns the water basins, the university café offers refreshments in the glassed-in round hall, and students, lecturers and even children and teenagers cavort everywhere, skateboarding and inline skating on the wide paths.

Initially a company headquarters, then a military base: the historic Johann Wolfgang von Goethe University campus has a long and varied history.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / imageBROKER / Stefan Espenhahn

There are only about 250 left in all of Germany, and very few are open to the public, but they are still up and running in Frankfurt: the paternosters, the nostalgic passenger elevators from the turn of the last century. Since health and safety forced the switch to closed lifts in the 1970s, these moving wooden boxes have become a rarity. Yet they are so much more fun to get – or more accurately hop – on and off of, which you can discover in the no fewer than eight chains of open boxes ceaselessly rotating in Frankfurt’s Goethe University central building. In the past, they were only open to university employees who had passed a special instruction course in the art of riding a paternoster and were monitored by specially hired security personnel. They are now open to the general public again though. The imposing architecture of the main university building that surrounds the clattering lifts is worth a look as well. Built around 1930 as the headquarters of chemical and pharmaceutical giant I.G. Farben, the 250-metre-long building is a memorial to a dark past, given that the company was involved in the distribution of the Zyklon B used in the gas chambers under the National Socialist regime and also operated its own concentration camp. Following the war, the US initially used it as a military base. Today the university is housed here, filling the space with more positive and peaceful energy. It is palpable in the huge linden trees and weeping willows growing in the historic greenspaces around the central building where small stone walls crisscross the meadows, a nymph sculpture adorns the water basins, the university café offers refreshments in the glassed-in round hall, and students, lecturers and even children and teenagers cavort everywhere, skateboarding and inline skating on the wide paths.

The new old town

Historic town centre of Frankfurt

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Jochen Tack

While other cities may argue over whose historic centre is the oldest, Frankfurt residents are proud of quite the opposite. Theirs is arguably the youngest “old” city in Germany, practically brand new really. As in many other cities, Frankfurt’s historic Medieval and Renaissance downtown was almost completely destroyed by air raids in World War II. During the post-war period, only the Römer – a central square with a historic town hall and large, half-timbered facades – was initially rebuilt. The rest of what had been the historic old town eked out a rather dreary existence in square, prefab buildings hastily erected in the 1950s. Then, after protracted debate, the city of Frankfurt finally decided to reconstruct its historic heart. But rather than just building historically accurate reconstructions, this resurrection was planned as a modern architectural experiment. A total of 35 buildings went up, 15 faithful reconstructions and 20 new designs stylistically based on the historic structures that proceeded them. These new buildings adhered to strict design specifications, like a limited colour palette, pointed slate roofs, and guidelines for the façade material. When possible, original pieces of the buildings destroyed in the war were incorporated into the new structures. So, since 2018, the narrow streets between the cathedral and the Römer have been repopulated by Renaissance, Baroque and Classicist style buildings with a lot of chic, cafes and expensive boutiques.

Historic town centre of Frankfurt

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Jochen Tack

While other cities may argue over whose historic centre is the oldest, Frankfurt residents are proud of quite the opposite. Theirs is arguably the youngest “old” city in Germany, practically brand new really. As in many other cities, Frankfurt’s historic Medieval and Renaissance downtown was almost completely destroyed by air raids in World War II. During the post-war period, only the Römer – a central square with a historic town hall and large, half-timbered facades – was initially rebuilt. The rest of what had been the historic old town eked out a rather dreary existence in square, prefab buildings hastily erected in the 1950s. Then, after protracted debate, the city of Frankfurt finally decided to reconstruct its historic heart. But rather than just building historically accurate reconstructions, this resurrection was planned as a modern architectural experiment. A total of 35 buildings went up, 15 faithful reconstructions and 20 new designs stylistically based on the historic structures that proceeded them. These new buildings adhered to strict design specifications, like a limited colour palette, pointed slate roofs, and guidelines for the façade material. When possible, original pieces of the buildings destroyed in the war were incorporated into the new structures. So, since 2018, the narrow streets between the cathedral and the Römer have been repopulated by Renaissance, Baroque and Classicist style buildings with a lot of chic, cafes and expensive boutiques.

Champions league am Main

The Eintracht Frankfurt women’s team (in black) playing the 1. FFC Turbine Potsdam (in red) at a Bundesliga game.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Eibner-Pressefoto / Ulrich Scherbaum

Football history is often made in Frankfurt. The Main metropolis kickers are nine-time German champions and have won the DFB Cup nineteen times. This is not, however, really down to the men. Although Eintracht Frankfurt, the male Bundesliga (top-tier German league) club, continues to hope to place in the Champions League every few years and won the German Championship in the distant past (1959), they simply cannot match their female counterparts, in rankings at least. While the men regularly have to settle for the UEFA European League Cup – which Franz Beckenbauer once called the “cup of losers”, Germany’s most successful women’s team, still independent as FFC Frankfurt until summer 2020, has already won four Women’s Champions League titles and dominated the Women’s DFB Pokal (German Football League) seven times. FSV Bornheim was also a small sporting gem for a long time. The men of the city district club managed to hold their spot in the second Bundesliga for years and brought star clubs such as 1. FC Köln and FC St. Pauli to the 12,000-seat stadium at the heart of the city where the crowd could be up close and personal with their favourite professional players. Since the club was relegated to the Regionalliga (Germany’s fourth tier) in 2017, fans now have to make the trek to the Commerzbank Stadium for the men’s Bundesliga and mingle with the 45,000 Eintracht fans. Incidentally, the women’s division was also the more successful at FSV Bornheim, with three championships and five cup victories, but was disbanded for financial reasons in 2006.

The Eintracht Frankfurt women’s team (in black) playing the 1. FFC Turbine Potsdam (in red) at a Bundesliga game.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Eibner-Pressefoto / Ulrich Scherbaum

Football history is often made in Frankfurt. The Main metropolis kickers are nine-time German champions and have won the DFB Cup nineteen times. This is not, however, really down to the men. Although Eintracht Frankfurt, the male Bundesliga (top-tier German league) club, continues to hope to place in the Champions League every few years and won the German Championship in the distant past (1959), they simply cannot match their female counterparts, in rankings at least. While the men regularly have to settle for the UEFA European League Cup – which Franz Beckenbauer once called the “cup of losers”, Germany’s most successful women’s team, still independent as FFC Frankfurt until summer 2020, has already won four Women’s Champions League titles and dominated the Women’s DFB Pokal (German Football League) seven times. FSV Bornheim was also a small sporting gem for a long time. The men of the city district club managed to hold their spot in the second Bundesliga for years and brought star clubs such as 1. FC Köln and FC St. Pauli to the 12,000-seat stadium at the heart of the city where the crowd could be up close and personal with their favourite professional players. Since the club was relegated to the Regionalliga (Germany’s fourth tier) in 2017, fans now have to make the trek to the Commerzbank Stadium for the men’s Bundesliga and mingle with the 45,000 Eintracht fans. Incidentally, the women’s division was also the more successful at FSV Bornheim, with three championships and five cup victories, but was disbanded for financial reasons in 2006.

Street festival rave

Frankfurt’s famous apple wine in a diamond-cut glass out of the traditional Bembel.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / dpa / Arne Dedert

Rumour has it that since the Middle Ages, people in Frankfurt have met up at the marketplace. Eintracht fans congregate at the farmer’s market near Konstabler Police Station, while night owls flock to the wine market on Friederberger Square. Collectors peruse the flea market on the banks of the Main River, and everyone really meets up at their local market for a cup of coffee and a natter with neighbours. The markets are the best places to try delicious local specialities, like grüne Soße (a cold sauce with fresh, seasonal herbs) or Handkäs mit Musik (a regional hard cheese served with chopped onions and caraway seeds) – ideally on the spot with a large glass of Ebbelwoi (apple wine) from a Bembel (a pot-bellied ceramic jug). It’s not just the perfect lunchtime treat, but also a good jumping off point for a fun evening out. On Fridays, the Friedberg market bursts at the seams with wine connoisseurs and revellers who gather around a couple of wine and food stands before moving on to the next activity. If you’re looking for more quiet fun, try “mini Friedberger Square”, which is not much more than a neighbouring traffic island where you can join the like-minded for a kiosk beer and some reggae. For a change of pace from the markets, there are the dozens of street festivals every summer. The Brückenwall Street Festival features fancy design and fashions stores, and the Berger Street Festival stretches over several kilometres as tens of thousands gather for an open-air party. There is also the more alternative Koblenzer Street Festival where bicycles are actioned off to the beat of electro music. Local residents and neighbourhood groups organize the festivals, setting up food stands and caipirinha bars to go with the raffles, flea markets and citizen’s initiative information booths as visitors party in the street until the wee hours.

Frankfurt’s famous apple wine in a diamond-cut glass out of the traditional Bembel.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / dpa / Arne Dedert

Rumour has it that since the Middle Ages, people in Frankfurt have met up at the marketplace. Eintracht fans congregate at the farmer’s market near Konstabler Police Station, while night owls flock to the wine market on Friederberger Square. Collectors peruse the flea market on the banks of the Main River, and everyone really meets up at their local market for a cup of coffee and a natter with neighbours. The markets are the best places to try delicious local specialities, like grüne Soße (a cold sauce with fresh, seasonal herbs) or Handkäs mit Musik (a regional hard cheese served with chopped onions and caraway seeds) – ideally on the spot with a large glass of Ebbelwoi (apple wine) from a Bembel (a pot-bellied ceramic jug). It’s not just the perfect lunchtime treat, but also a good jumping off point for a fun evening out. On Fridays, the Friedberg market bursts at the seams with wine connoisseurs and revellers who gather around a couple of wine and food stands before moving on to the next activity. If you’re looking for more quiet fun, try “mini Friedberger Square”, which is not much more than a neighbouring traffic island where you can join the like-minded for a kiosk beer and some reggae. For a change of pace from the markets, there are the dozens of street festivals every summer. The Brückenwall Street Festival features fancy design and fashions stores, and the Berger Street Festival stretches over several kilometres as tens of thousands gather for an open-air party. There is also the more alternative Koblenzer Street Festival where bicycles are actioned off to the beat of electro music. Local residents and neighbourhood groups organize the festivals, setting up food stands and caipirinha bars to go with the raffles, flea markets and citizen’s initiative information booths as visitors party in the street until the wee hours.

“Frankfurt helau, Offenbach pfui!” (Frankfurt hurrah, Offenbach boo!)

Open-air cinema in Hafen 2 in Offenbach.

| Photo (detail): © suesswasser e.V.

It is almost de rigour for neighbouring cities, like Frankfurt and Offenbach, to engage in a long-standing and (mostly) friendly rivalry. No Frankfurt Shrove Tuesday would be complete without a jibe or two at its smaller neighbour. After all, the best thing about Offenbach is that it has a glorious view of Frankfurt. This love-hate relationship is thought to go back to the late Middle Ages and disputes over castle rights followed by countless territorial, denominational and economic conflicts. But Frankfurt would be a bit lost without its annoying little sister too. There is a serious risk of traffic jams on the riverside path to Offenbach when the nice summer weather brings out all the pedestrians, cyclists and pushchair pushing parents. Whether its yea or nay to Offenbach, there is no better way to spend a lovely day than strolling along the green banks of the Main River, dropping in for coffee, an open-air concert, or night at the cinema with a river view at Hafen 2 or the Waggon am Kulturgleis. House and techno fans won’t want to miss the Robert Johnson, one of the cities best-known clubs even if it did have the misfortune to be located in Offenbach.

Open-air cinema in Hafen 2 in Offenbach.

| Photo (detail): © suesswasser e.V.

It is almost de rigour for neighbouring cities, like Frankfurt and Offenbach, to engage in a long-standing and (mostly) friendly rivalry. No Frankfurt Shrove Tuesday would be complete without a jibe or two at its smaller neighbour. After all, the best thing about Offenbach is that it has a glorious view of Frankfurt. This love-hate relationship is thought to go back to the late Middle Ages and disputes over castle rights followed by countless territorial, denominational and economic conflicts. But Frankfurt would be a bit lost without its annoying little sister too. There is a serious risk of traffic jams on the riverside path to Offenbach when the nice summer weather brings out all the pedestrians, cyclists and pushchair pushing parents. Whether its yea or nay to Offenbach, there is no better way to spend a lovely day than strolling along the green banks of the Main River, dropping in for coffee, an open-air concert, or night at the cinema with a river view at Hafen 2 or the Waggon am Kulturgleis. House and techno fans won’t want to miss the Robert Johnson, one of the cities best-known clubs even if it did have the misfortune to be located in Offenbach.

Subculture in the shadow of the bank towers

Graffiti on the construction fence for the new ECB building.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Boris Roessler

At the turn of the millennium, news made the rounds that a new tower was to be built in Frankfurt, a creative design right on the banks of the Main River – but not in the banking district. The European Central Bank (ECB) had outgrown its building on Wilhelm Brandt Square and, since there was no space in the bank quarter for a new building, they outsourced to the Ostend. The structure was to rise on the former site of the wholesale market whose historic warehouses were to be artfully incorporated into it. The construction of the ECB also marked the beginning of the complete redevelopment of the inner-city district, rather neglected until then, making it still somewhat affordable. Today, construction projects worth billions are springing up here and taking rents sky-high with them. Still, the city made sure the area did not develop into a second banking district by expanding the meadows on the banks of the Main and adding a skate park, several football pitches and basketball courts, a playground and outdoor exercise equipment. Now in at the foot of the shiny glass ECB twin towers, Frankfurt’s skaters and bikers show off their skills, rappers jam under the pillars of Honsell Bridge, while the Lola Montez Art Association organizes contemporary art exhibitions, electro parties and alternative design and Christmas markets under the arches of the bridge. In August, one of the city’s most enchanting open-air events, the “Sommerwerft” theatre festival, takes place right at the foot of the giant mirrored tower. A little insider’s tip: The perhaps most beautiful view of Frankfurt’s skyline on a sunny day is from the railroad bridge between the ECB and the skate park – especially at dusk when it is backlit by the setting sun.

Graffiti on the construction fence for the new ECB building.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Boris Roessler

At the turn of the millennium, news made the rounds that a new tower was to be built in Frankfurt, a creative design right on the banks of the Main River – but not in the banking district. The European Central Bank (ECB) had outgrown its building on Wilhelm Brandt Square and, since there was no space in the bank quarter for a new building, they outsourced to the Ostend. The structure was to rise on the former site of the wholesale market whose historic warehouses were to be artfully incorporated into it. The construction of the ECB also marked the beginning of the complete redevelopment of the inner-city district, rather neglected until then, making it still somewhat affordable. Today, construction projects worth billions are springing up here and taking rents sky-high with them. Still, the city made sure the area did not develop into a second banking district by expanding the meadows on the banks of the Main and adding a skate park, several football pitches and basketball courts, a playground and outdoor exercise equipment. Now in at the foot of the shiny glass ECB twin towers, Frankfurt’s skaters and bikers show off their skills, rappers jam under the pillars of Honsell Bridge, while the Lola Montez Art Association organizes contemporary art exhibitions, electro parties and alternative design and Christmas markets under the arches of the bridge. In August, one of the city’s most enchanting open-air events, the “Sommerwerft” theatre festival, takes place right at the foot of the giant mirrored tower. A little insider’s tip: The perhaps most beautiful view of Frankfurt’s skyline on a sunny day is from the railroad bridge between the ECB and the skate park – especially at dusk when it is backlit by the setting sun.

From painted masterpieces to the underground

The “Skylines” series is set in Frankfurt.

| © Netflix

Speaking of Ostend – the district with its old harbour area is also home to no fewer than two studio buildings in which artists of all stripes have set up shop. Frankfurt has long been known as a city of art with the Städel Museum’s extensive collection of paintings, the Museum of Modern Art and the Schirn Kunsthalle for contemporary art. Frankfurt’s Academy of Communication and Design ensures that plenty of art is made in the city. The metropolis on the Main has also become one of Germany’s dance cities thanks to contemporary choreographer Willian Forsythe who joined the Frankfurt Ballet in 1984. Along with all this high culture, Frankfurt can also do underground, and the hip-hop scene has recently made a name for itself with rappers like Azad, Haftbefehl and Celo & Abdi. A fact little known outside hip-hop circles until Netflix brought the topic to the big screen with the 2019 Skylines series which is set in Frankfurt’s rap industry: “Frankfurt is a cosmopolitan city in a very small space where it feels like everything revolves around business,” screenwriter Dennis Schanz said about the show’s setting. “Yet this is where the different worlds clash more harshly than anywhere else in Germany. Rich and poor, bourgeoisie and criminal, city and country.” It would be hard to sum it up better. Incidentally, the first really successful series out of Frankfurt this millennium covered a less surprising topic: in Bad Banks, everything revolves around intrigue and competition in the investment sector of major banks.

The “Skylines” series is set in Frankfurt.

| © Netflix

Speaking of Ostend – the district with its old harbour area is also home to no fewer than two studio buildings in which artists of all stripes have set up shop. Frankfurt has long been known as a city of art with the Städel Museum’s extensive collection of paintings, the Museum of Modern Art and the Schirn Kunsthalle for contemporary art. Frankfurt’s Academy of Communication and Design ensures that plenty of art is made in the city. The metropolis on the Main has also become one of Germany’s dance cities thanks to contemporary choreographer Willian Forsythe who joined the Frankfurt Ballet in 1984. Along with all this high culture, Frankfurt can also do underground, and the hip-hop scene has recently made a name for itself with rappers like Azad, Haftbefehl and Celo & Abdi. A fact little known outside hip-hop circles until Netflix brought the topic to the big screen with the 2019 Skylines series which is set in Frankfurt’s rap industry: “Frankfurt is a cosmopolitan city in a very small space where it feels like everything revolves around business,” screenwriter Dennis Schanz said about the show’s setting. “Yet this is where the different worlds clash more harshly than anywhere else in Germany. Rich and poor, bourgeoisie and criminal, city and country.” It would be hard to sum it up better. Incidentally, the first really successful series out of Frankfurt this millennium covered a less surprising topic: in Bad Banks, everything revolves around intrigue and competition in the investment sector of major banks.

Comments

Comment