Saving Resources

Leaving No Traces

Not to harvest more than what is needed – that is the basic understanding of the Sámi. How does this fit together with a capitalist society in which nature is increasingly being exploited? Susanne Hætta writes about the threat posed to the Indigenous people by human-made climate change.

By Susanne Hætta

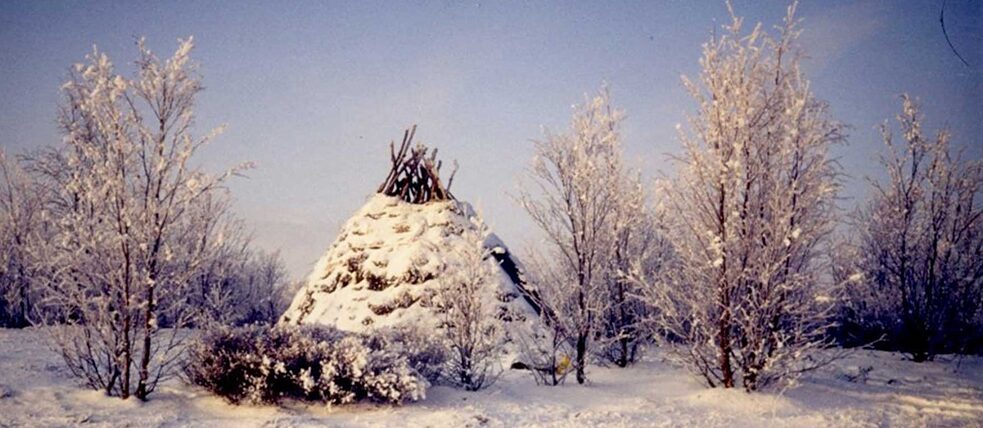

At the forest margin, a few metres from my family’s cabin in the area my father comes from lies an overgrown pile of peat and the remains of tree trunks. Now almost covered with grass and flowers, it used to be a small goahti, a Sámi cone-shaped hut, where my father used to smoke fish and reindeer meat.

As a child, I sometimes played inside the goahti. Later, I couldn’t understand why they left it to disintegrate into a pile of wood when it was no longer being used. Many years later, I understood the purpose of this.

The Sámi are the Indigenous people of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. I am a Sámi living in the northernmost region in the Norwegian part of Sápmi, which is what we call our land. Though a very modern people, we still have a shared culture and many traditional uses for various natural resources – even Sámi like myself. I don’t derive my income from nature, but I harvest, I fish and I feel the weight of the legacy of my forebears – not as a burden, but as a responsibility I carry with pride.

The enormous differences in mentality and perception of reality between colonial capitalism and sustainable, moderate utilisation of natural resources are almost insurmountable, with the latter involving a significant obligation to tradition, to family and to the local area. Achieving this demands respect and gratitude for the bounty that nature provides. This is something that is circular, seasonal and sustainable. The woman harvesting reindeer moss so as to have some extra fodder for her herd of reindeer knows that she should not harvest in the same place the following year. The vegetation needs to be able to grow back so that it can be harvested anew, time after time, but at a frequency nature can tolerate. A fishing lake is not fished to depletion by the local people but is husbanded so that they can catch what they need, year after year. Even though not all Indigenous people live by this knowledge, it is something internal – a knowledge that rarely lies more than a generation back, and it can be rediscovered and revitalised.

THE ENVIRONMENT IS SOLD OFF FOR A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS

It ought to be so simple, yet it is utterly impossible for people to live by this knowledge if they have no affinity to the place and to the mentality that is embodied in the culture.For the agents of capitalism, and its means of production, are people – however strange that sometimes seems, as giant machines advance through landscapes that are not their own, in order to take resources located far from their own localities.

But are we Indigenous people part of the problem too? Perhaps Sámi should not be eating farmed scampi from Vietnam, the Japanese should not be eating king crab from Norway and Americans should not be eating farmed salmon from Scotland. One paradox of the climate crisis in which we are unquestionably implicated is that we have to turn our gaze closer to home, both to experience the obligations deriving from sustainable resource use and to reverse the emissions from transporting food halfway around the world.

The fundamental Sámi concept of nature – that you must not leave behind anything that does not break down naturally and not harvest more than you need – is something we share with many other Indigenous peoples. We have a strong affinity and obligation to family and to our local community, as is reflected in, among other things, how our society is organised and in our mythology.

Unfortunately, the wider society, legislators and national politicians rarely listen to us. This is why nature conservation organisations have become allies in our fight against constant encroachments on Sámi land. More ecologically sustainable exploitation of natural resources will inevitably lead to fewer jobs globally, but also less transport and hence lower emissions, and – not least – lower profits for the business owners; business owners who are often not in the same country or even the same continent as the natural environments they are exploiting, whether it is wind power or mines. Politicians avoid taking unpopular measures that would give Indigenous and local populations the final say on matters that affect where they live and the natural resources they depend on – steps that would put a stop to the exploitation of natural resources by external actors intent only on delivering the highest possible profits to their shareholders. The natural environment is sold off for a fistful of dollars, or the promise of a handful of local jobs.

HELPING REMEMBER

The word ‘development’ seems to have taken on a religious significance for capitalist forces, becoming almost something of a sacred cow, wholly inviolable. The big problem is that ‘development’ does not mean the same thing to everyone, or does not apply to everyone. The result is the unchallenged ability of capitalists to exploit natural resources and sideline Indigenous people, because interfering with ‘development’ – a runaway excavating machine with a bottomless appetite, but no eyes – is taboo. After all, no politician wants to be responsible for halting development.If it were left up to companies operating on purely capitalist and sometimes colonial principles to take responsibility for Indigenous peoples’ land, nature and resources, then the world would be heading for destruction. Sadly, that is what is happening. Politicians lack the power they need to stand up to big business, which is why international collaboration is required, together with a renaissance for the value systems of Indigenous people and their sustainable use of natural resources.

As I write this, it is midsummer in northern Sápmi. The mosquitos are buzzing, the fish are jumping, and we are eagerly awaiting this year’s cloudberry harvest – our gold. This brings me back to the goahti that was once erected close to what is now our holiday cabin, in the area that my father’s family comes from and where they still live. The goahti is more overgrown than I remember from my previous visits. Soon it will merge with the forest margin, and only we will know that it was ever there. I like that idea.

And that’s why I take photographs. In order to know, to help remember; so that my children and grandchildren will know, remember and – hopefully – move through this world respecting the knowledge that nature is there to be used but not used up. That you must not take more than you need. And that you must not leave any traces that nature cannot reclaim.