Climate Science in Canada’s North

Vital Clues About the Future of a Warming Planet

In the winter of 2010, the 1,200 residents of the mostly Inuit village of Nain, in Canada’s far northeast, lived through a natural disaster unnoticed by the rest of the world. From January to March—when the region is typically gripped by a deep freeze—average temperatures hovered far above normal, frequently above the freezing point. The sea ice was thin, cracked, and pockmarked with open patches. Hunting was risky, food ran low, and at least one ice traveller drowned when their snowmobile plunged through weak ice.

By Matthew Halliday

Ice travel has never been risk-free, of course. For centuries, Inuit have relied on time-tested means of mitigating risk—paying attention to ice’s colour, texture, or the resistance it offers a sharp harpoon blow. But 2010 was different. “There was a terrible sense of loss, and anxiety about what it meant for the future,” says Robert Way, a climatologist of Inuit heritage at Canada’s Queen’s University.

Reorient research to local priorities

2010 was also a year of celebration, however, as the fifth anniversary of the birth of Nunatsiavut, a vast, self-governing Inuit territory, of which Nain is administrative capital.The fledgling government had few resources to handle an existential climate threat, but it did have plenty of outside researchers traipsing through its enormous backyard. In the past, those researchers’ work rarely felt relevant to locals. “Researchers would come through, do their work, not tell anyone what they were doing, and then leave,” said Carla Pamak, the Nunatsiavut government’s Inuit Research Adviser, who lives in Nain.

So that June, the government hosted the Tukisinnik Community Research Forum, bringing together locals with select academics, hoping to reorient research to local priorities—sea ice high among them, especially after that disastrous winter. “Out of it came an understanding that research is something the community can control for its own benefit,” says Trevor Bell, a participant and geography professor with Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

A map of travel hazards

Bell may be best known for SmartICE. Created in collaboration with the Nunatsiavut government, SmartICE integrates traditional ice knowledge with real-time data gathered from sensors embedded in, and pulled across, sea ice. Piloted in Nain in 2012, it aims to generate a map of travel hazards, accessible by desktop or smartphone, to complement traditional knowledge.It’s not alone. In the past decade, Canada’s four Inuit regions, from the Alaskan border to the Atlantic, have taken greater control of research in their communities. The consequences could transform science in a part of the world that holds vital clues about the future of a warming planet—but where the legacy of science-as-usual remains shadowed by centuries of exploitation.

Many Indigenous communities worldwide have a fraught relationship with academia, and Inuit are no different. In the 19th century, Inuit were featured as anthropological oddities in travelling expositions. In the 1970s, Canadian researchers are alleged to have used them as human test subjects, performing skin grafts and measuring pain responses.

‘Sorry, but you’re actually behind.’

But a wave of Inuit political activism in recent years has begun producing serious structural change in Canada’s political landscape, and the scientific landscape may be next. In 2018, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the group that represents Inuit interests federally in Canada, launched the National Inuit Strategy on Research (NISR), aiming to elevate research self-determination for Inuit in their homeland.“The academic community often thinks of itself as enlightened, or very progressive,” says ITK president, Natan Obed, originally from Nain. “And we as Inuit are walking into this room, crowded with non-Inuit, and saying, ‘Sorry, but you’re actually behind.’”

One of ITK’s chief complaints focuses on research funding. Because Inuit are rarely represented on government or university granting bodies, funding has skewed heavily to biological and physical sciences, rather than social sciences, where more immediate Inuit concerns often lie.

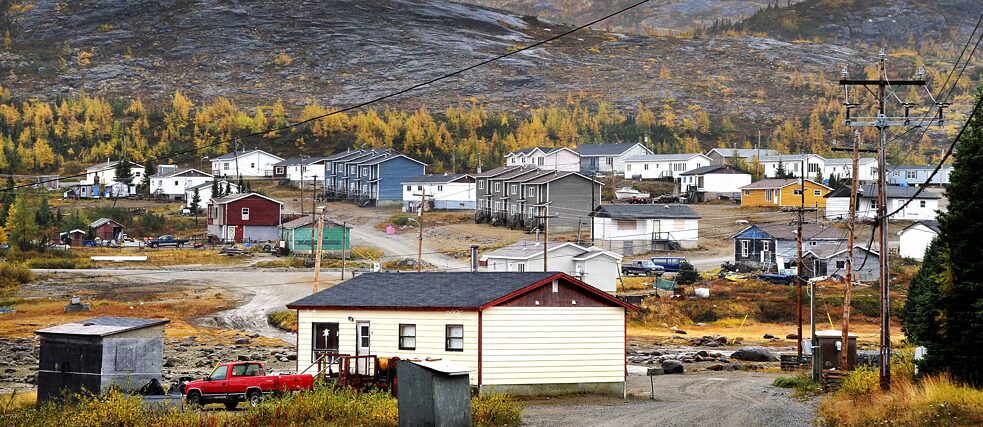

Addressing those concerns is one of the chief goals of the Nunatsiavut Research Centre, one of only three Inuit-owned research facilities in Canada. Housed in a plain, two-storey office building next to Nain’s only hotel and restaurant, it consists of two small labs, a kitchenette and common area, offices, and overnight accommodations. Its success has gone hand-in-hand with Nunatsiavut’s political autonomy. Carla Pamak says many goals of the NISR have already been met in Nunatsiavut. “And a lot of what has happened here,” she says, “has sparked the national strategy.”

What the icebound world means to Inuit

SmartICE owes much of its success to the Centre, and it’s not alone. McGill University associate professor Bruno Tremblay studies sea-ice mechanics, travelling regularly to Nain to study the effect of tides and wind on landfast ice, anchored to the shore or the ocean floor. His research involves deploying buoys to develop more accurate predictive models of sea-ice coverage. He shares data freely with community members and consults with the community on where to place buoys, to address concerns of interest to both. “There will always be interesting science questions no matter where we deploy,” said Tremblay, “so we try to go with their priorities.”Tremblay works regularly with Joey Angnatok, a fisherman, handyman, and part-time citizen scientist. Angnatok helps non-locals glean at least a little of what the icebound world means to Inuit, recounting history, stories, and families associated with particular islands, bays, and locales.

As a search-and-rescue volunteer, Angnatok also knows intimately the dangers inherent to ice travel. He was instrumental to SmartICE’s pilot phase, helping southern researchers get the lay of the land, and deploying and checking buoys.

“I’ve always been sort of a science geek,” Angnatok said. “I’d talk to elders and they’d say, ‘Oh I’ve never seen a hole there in the ice before, I wonder what’s going on?’ And then you talk to researchers and they’d be able to talk about water salinity and other observations, and you begin to see how it works together.”