Techno

A (not entirely) German timeline from 1989 to the present day

Techno started in Detroit and went around the world, but nowhere else did the futuristic sound find such fertile ground as in Germany. As a soundtrack to the end of the Cold War, the ensuing scene experienced classic highs and lows before experiencing a new resurgence at the end of the noughties.

By Kristoffer Cornils

Detroit roots, international enthusiasm

Inspired by Kraftwerk’s trips on the Autobahn, the glam and glitz of Italian disco productions and the futuristic funk of American artists like Bootsy Collins, a few kids from Detroit started playing about with Japanese hardware in the 1980s. The singles Sharevari by A Number of Names in 1981 and No UFO’s by Juan Atkins’ project “Model 500” four years later laid the foundations for the soundtrack of a new musical future: techno.

This sound, which was born out of global cooperation, found its way into the big wide world at lightning speed. While Acid House from Chicago – with a detour via Ibiza – kicked off an entire movement, by 1988 the compilation Techno! (The New Dance Sound Of Detroit Techno) emphasised that the “Motor City” also had a new aesthetic to offer the world – and it was eagerly welcomed by the public.

Although both house and techno should be understood as international phenomena, they cannot be explained without their specific historical, social and cultural contexts and traditions: there would have been no Chicago house music without the highs and lows of the New York’s queer disco scene, no techno without the experiences and hopes of the Black youth of Detroit, the Techno City, as it is called in the title of an EP by Juan Atkins’ duo with Richard “3070” Davis.

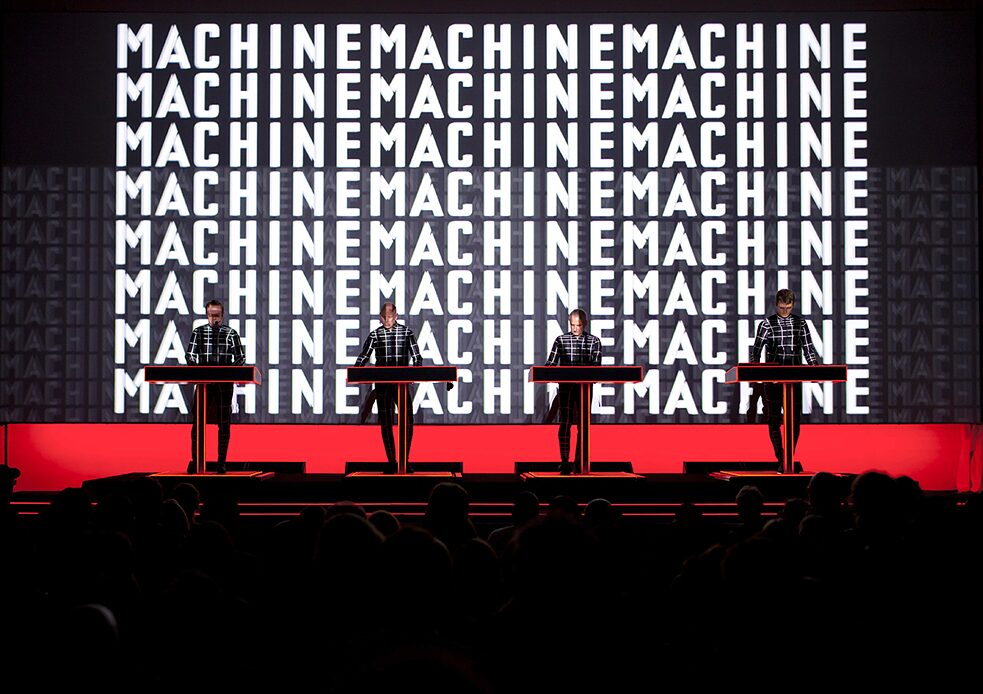

The work of German band Kraftwerk in the early 1980s blazed a trail for the techno scene that followed.

| Photo: © picture alliance / Peter Boettcher / dpa

But above all techno has asserted itself as an inclusive culture, which kept on experiencing ramifications and created reciprocal effects on both a global and regional scale. So it isn’t possible to write a uniform history of techno – as can be seen from the example of Germany.

The work of German band Kraftwerk in the early 1980s blazed a trail for the techno scene that followed.

| Photo: © picture alliance / Peter Boettcher / dpa

But above all techno has asserted itself as an inclusive culture, which kept on experiencing ramifications and created reciprocal effects on both a global and regional scale. So it isn’t possible to write a uniform history of techno – as can be seen from the example of Germany.

West Germany on synthesizer

The German “Krautrock” bands at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s had already displayed a heightened interest in synthesizers and cosmic sounds. Especially in Kraftwerk’s home city of Düsseldorf the subsequent generation consolidated their engagement with synthesizers, sequencers and drum machines, which could now be obtained cheaply: groups like D.A.F. are generally held responsible for the Neue Deutsche Welle, but by the same token they laid the foundation for electronic dance music from the Federal Republic of Germany.

Before the term “techno” arrived here from Detroit, Andreas “Talla 2XLC” Tomalla, so the story goes, wrote this word on a shelf in the City-Music record shop in Frankfurt am Main, and even followed this with a series of events entitled Technoclub. In a city whose culture was strongly influenced by the presence of Black American armed forces, much of the framework for a German interpretation of the techno culture was already established: clubs like the Dorian Gray and later the Omen, DJ and musician Sven Väth and GROOVE magazine – which was founded by Thomas Koch alias DJ T. – as well as the Frontpage magazine, which emerged in the context of the Technoclub events, became important cornerstones of the early scene.

1989: the turning point

Alongside Frankfurt am Main there were other hotbeds of electronic music culture in West Germany, for example the gay scene club Front in Hamburg. But the new sound from Detroit didn’t meet with such resonance anywhere else as it did in Berlin. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, revellers from West and East Berlin came together on the dance floor – it truly was a turning point for techno in Germany. One half had been dancing to acid house in the cellar clubs of Schöneberg, while the others were brought up on Western pop, hip-hop and club music broadcast by DT64 radio station for young people.

Vacant premises in the reunified city were filled with provisional clubs, with the temporary appearance of autonomous zones where the musical mixture was almost limitless: in the early days they still referred to it indiscriminately as “technohouse”, which was then joined by breakbeats and other forms of electronic dance music. But – thanks in part to DJs like Tanith and organiser of the Tekknozid techno raves Wolle XDP – a hard, insistent sound for long raves was only around the corner: Tekkno was the first form of techno that was genuinely from Berlin.

Until its closure in 2005 the “Tresor” was the best-known of the techno temples in Berlin.

| Photo: © picture-alliance/dpa/dpaweb/ XAMAX

Until its closure in 2005 the “Tresor” was the best-known of the techno temples in Berlin.

| Photo: © picture-alliance/dpa/dpaweb/ XAMAX

But that didn’t happen without causing ripples across the globe either. Music published on labels like R&S from Belgium, Djax’ Djax Records from the Netherlands and especially Underground Resistance from Detroit became formative for Klang der Familie, as a track by Dr. Motte & 3Phrase was called, which also gave its name to a book about the early Berlin scene published in 2012.

A particular Berlin-Detroit connection was made between the Tresor club run by Dimitri Hegemann and members of the group around “Mad” Mike Banks and Jeff Mills, who countered the soft grooves of the first wave of Detroit techno with that hard, insistent sound – and that wasn’t all. As an “Underground Resistance” they also represented a political interpretation of techno, which emphasised the Black roots of the sound and united a musical hardness with minimalist structures.

The early 1990s: anarchistic style explosion and mainstreamisation

Meanwhile Berlin was not the only German city to have established a scene that developed its own unique sound. Throughout the nineties it was mainly clubs like Stammheim in Kassel, milk! In Mannheim, the Distillery in Leipzig – still in existence today – and the scene associated with the Cologne record store Kompakt – later a label empire – that were responsible for an anarchistic style explosion in reunified Germany. Yet, the diversity that was after all based on the lively exchange amongst them was soon levelled by the burgeoning success of electronic dance music.

If there is such a thing as zero hour for the arrival of techno in the German mainstream, then it’s probably the release of the single Somewhere Over the Rainbow by Marusha during 1994. The long-standing DT64 announcer topped the charts with her cover version of the classic – which some viewed as a sell-out of a sub-culture, while others celebrated it as a huge success.

With DJ Marusha’s “Somewhere over the Rainbow”, techno arrived in the mainstream in 1994 – for better or worse.

| Photo (detail): ©picture alliance/Fryderyk Gabowicz

In fact the Love Parade, which was first hosted in Berlin in 1989 by Dr. Motte and Danielle de Picciotto, was already an international phenomenon by this point, and it would soon be broadcast live on music television. A few resourceful corporations had also discovered the rave culture as an ideal advertising vehicle. As a TV commercial, on the radio, in the charts and in kids’ bedrooms: the “made in Germany” techno culture was colourful and strident – and could be seen and heard everywhere. It became mainstream almost overnight.

With DJ Marusha’s “Somewhere over the Rainbow”, techno arrived in the mainstream in 1994 – for better or worse.

| Photo (detail): ©picture alliance/Fryderyk Gabowicz

In fact the Love Parade, which was first hosted in Berlin in 1989 by Dr. Motte and Danielle de Picciotto, was already an international phenomenon by this point, and it would soon be broadcast live on music television. A few resourceful corporations had also discovered the rave culture as an ideal advertising vehicle. As a TV commercial, on the radio, in the charts and in kids’ bedrooms: the “made in Germany” techno culture was colourful and strident – and could be seen and heard everywhere. It became mainstream almost overnight.

But were “air raves” funded by tobacco firms and held in aeroplanes really compatible with the underground ethos of the scene? What did the inebriated goings-on during the Love Parade have to do with the future visions of Detroit kids like Juan Atkins, who had used a phrase coined by futurist Alvin Toffler to describe himself as a “techno rebel”? Were star cut-outs in BRAVO magazine in line with the Underground Resistance ideology, in which they preferred their techno to be “faceless”, neither permitting advertising nor showing their faces?

Not really – the thing is, Germany’s techno scene was driven by the idea of a “raving society”, something also dreamed of by WestBam, one of the leading DJs and label operators of the late 1980s. Arriving in the mainstream was the logical consequence of this megalomaniac claim – for better or for worse.

The late 1990s: the era of the “super DJs”

After techno had reached its zenith in the mid-1990s it gradually lost public impact in Germany, however at the same time the style spectrum diversified. From digital hardcore and gabber to drum’n’bass, experimental sound art on labels like Mille Plateaux, or trance, schranz and breakcore, created or consolidated certain niche sounds – and a fair few of these still quite new communities disappeared into the background.

The late 1990s were characterised by a waning influence in techno in the mainstream, but at the same time also of the emergence of those individuals WestBam would retrospectively call “Superstar DJs”. DJs like Paul van Dyk were active on a global scale, were highly paid and delivered one-man entertainment by the hour. As a result the techno movement split into two layers: the regional underground with its rigid insistence on authenticity, and a team of internationally touring DJs whose bulging bank accounts helped them to make the leap from the high times of techno hype into the new millennium.

The 2000s: minimalism and a resurgence

From a commercial point of view the timespan between the rise and fall of techno as a mainstream phenomenon might have been hard for the scene, which was distributed across the country, but on a creative level it involved some exciting innovations. For a long time labels such as Source from Heidelberg or the Berlin institutions Chain Reaction and Basic Channel in association with the Hard Wax record store had been generating new stylistic impulses, mixing other sounds in with techno or creating something entirely abstract. Around the turn of the millennium the time had come for consolidation. More specifically, that meant minimalism.

“You have come here, you must think about minimalism,” was how Sascha Kösch articulated his welcome to listeners in the liner notes for the Clicks_+_Cuts compilation at Mille Plateaux in 2000. The extensive anthology consisted of contributions that rearranged the sounds of the computer age and used them to create a collage. Similar principles were applied in new genres such as microhouse. The new trend towards minimalism resulted in a throwback: Minimal techno became the sound of the noughties in techno Germany.

Minimal techno, which was invented by Detroit producer Robert Hood in the mid-1990s, was based on a stripped-down sound aesthetic and brought the music back to its original function as dance music: repetitive rhythms, combined with slight shifts, were designed to lull dancers into a trance over the duration of a marathon rave. This approach found an especially receptive breeding ground in Berlin, where they turned many a night into day and vice versa at clubs like Bar25 or the Berghain. The rave was never going to end there, it seemed. Word soon got round.

At the latest with the film Berlin Calling and the title theme Sky & Sand released in 2008 by lead actor Paul Kalkbrenner together with his brother, a singer known as Fritz, the Berlin scene – which had until then mostly been viewed as an international inside tip – got a massive boost almost overnight. The “Easyjetset”, a term coined by journalist Tobias Rapp for the weekly planeloads of techno tourists from all over the world, had existed already but now boomed even more, and techno made in Berlin became an exportable hit again. A resurgence began towards the end of the 2000s.

The aftermath: the Love Parade disaster in 2010 and the gentrification of the dancefloor

But one thing shown by the Love Parade disaster on 24th July 2010 in Duisburg, when several people died as a result of mass panic, was that techno culture’s return to the mainstream and the revived interest of big businesses – the parade was sponsored by a chain of fitness studios – went hand-in-hand with new and negative consequences.

Since the start of the 2010s techno has been experiencing an international upturn from which primarily old and new superstar DJs are benefiting – both EDM megastars like David Guetta or headliners emerging from the underground such as Charlotte de Witte, Kobosil or Peggy Gou – while the underground continues its precarious existence. Even in Berlin the club scene is at risk of being squeezed out. The faster, higher, wider ideology of German techno culture was leading straight to a gentrification of the dancefloor. And the outcome? So far that’s uncertain.

Comments

Comment