The latest trends

Children’s and young adult books in German

For years, a long list of hard-to-answer questions has dominated discussion about the state and the future of literature for children and young adults in German. In autumn of 2017, for instance, the latest catchphrases are: How can we explain parents’ lack of desire to read aloud to their children, the increasing absence of teenagers and young mothers from book stores, the lack of convincing concepts for additional digital book offers, or even the oft-bemoaned uniformity of publishers’ programmes moving towards the “mainstream,” or all of them producing the same old stuff? How are these phenomena related? And how do they react to the widely expressed desire for more educational efforts?

It doesn’t look bad at all at first glance. Every year around 9,000 titles are still being published, about two-thirds of which are by German-speaking authors. And sales of children’s and young adult books have plummeted far less than book sales in general this year – albeit with large differences depending on the young group targeted. Just behind general fiction books, children’s and young adult books continue to be the second largest segment of the entire book market.

Anyone who is always looking for the same old stuff will find it in countless books about cute polar bears or unicorns, and German-language fantasy books, though declared dead many times, are still being churned out. The variety in the current programs has been great for years, not least because of the stimuli provided by new and small publishing houses with unusual books. For example, there’s luftschacht in Austria, where provocative novels and graphic novels for adults stand as equals alongside powerful children’s books like Michael Roher’s Tintenblaue Kreise (Ink-Blue Circles), or Kunstanstifter in Germany, who publish surprisingly aesthetically illustrated – recently award-winning – books, which at first glance do not reveal whether they are aimed at older or younger audiences (Kilian Leypold and Ulrike Möltgen, Wolfsbrot (Wolf’s Bread), 2017 or Christina Röckl, Und dann platzt der Kopf (Then the Head Explodes), 2014).

So anyone who demands more from a book than mediocrity certainly is spoilt for choice both with regard to content and design. In the picture book segment, Swiss publishers like NordSüd (Pei Yu Chang: Mr. Benjamin’s Suitcase of Secrets, 2017) and atlantis (with projects such as those by Kathrin Schärer and Lorenz Pauli), as well as German ones like Gerstenberg (books by Julie Völk) or Beltz & Gelberg (Nikolaus Heidelbach, Schornsteiner (the story of a flue brush), 2017) have issued reliably offbeat, sophisticated books for years while also always promoting new, young illustrators. Narrative children’s books rely more and more on illustrations and are particularly enchanting when the pictures do more than merely illustrate the words (Silke Schlichtmann and Ulrike Möltgen, Bluma und das Gummischlangengeheimnis (Bluma and the Secret of the Rubber Snake), Hanser 2017 or various volumes from the Dramatiker erzählen für Kinder series published by mixtvision). Others play with combinations of narrative text and built-in graphic novel elements, of which mainly Martin Baltscheit and Finn-Ole Heinrich have supplied wonderful examples in recent years. The topics are extensive, ranging from friendly vacation stories to the exemplary story of a boy who undermines his classmates’ bullying by helping his opponents out of a major jam. In addition to works by younger story-tellers such as Lena Hach, Kirsten Reinhardt and Oliver Scherz are the books by veterans like Jutta Richter, Paul Maar, Cornelia Funke and Andreas Steinhöfel. And in non-fiction, in addition to playful books on fields of knowledge such as archeology or space, there are also political topics in words and pictures, in books on the rights of children, or in the form of answers to children’s questions entitled Wenn ich Kanzler von Deutschland wär (If I Were Chancellor of Germany) by Jan von Holleben and Lisa Duhm (Thienemann, 2017). By contrast, the wave of well-intentioned books on refugee issues seems to have dwindled. And it is still unclear why, in a multicultural society, people with dark skin or a headscarf are almost always depicted only in connection with crises, as victims, as the persecuted or even as perpetrators.

In young adult books, with their fluid boundaries to books for all ages or adults, things are more dramatic. This applies to romantic and fantasy books, which merge love and heroism, as well as those books that address current problems and crises of identity – such as science fiction on the issue of repulsing refugees on the borders of heavily armed, authoritarian states (Martin Schäuble, Endland, Hanser 2017). The topic of killing sprees has also not lost its appeal (Lea-Lina Oppermann, Was wir dachten, was wir taten (What We Thought, What We Did), Beltz & Gelberg, 2017) and preoccupation with life in Nazi Germany is always looking for new topics and forms to portray the German past for young readers in a contemporary way (Johannes Herwig, Bis die Sterne zittern (Until the Stars Tremble), Gerstenberg 2017).

The latest novels by Sarah Michaela Orlovský (ich #wasimmerdasauchheißenmag (I #whateverthatmeans), Tyrolia 2017) and Tamara Bach (Vierzehn (Fourteen), Carlsen 2016) show how serious a novel can take Peter Härtling’s remarks that in children and young adult books the unprecedented experiences of the beginning always need to search for their language anew. Both barely cross the boundaries of seemingly uneventful everyday life, but process all those forms of expression available to their youthful heroines – journals and e-mail, texting and inner monologues –in very different ways. But they are not ingratiating, they do not imitate teen language, but produce a tone that perhaps sounds the way young people would like to speak: noticeably more concise, more differentiated than in everyday life.

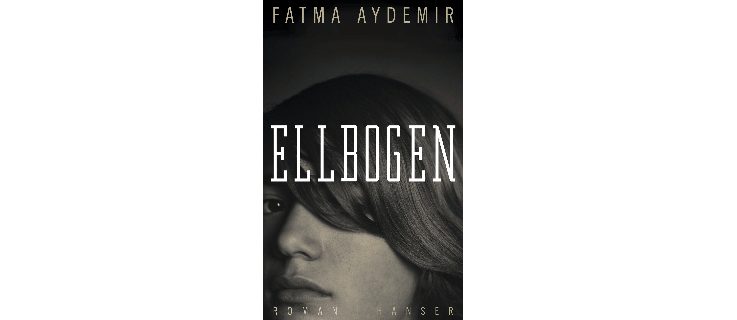

For a long time now, books about young adults published for adults are also enriching the YA segment. Although the discussion about the all ages target group has been cooling down for some time now, it hasn’t changed prolonged adolescence. An emphatically impetuous book like Fatma Aydemir’s Ellbogen (Hanser, 2017), for example, set in Germany and Istanbul, overshadows a lot of what youth book publishers usually have to offer on topics such as integration or immigration and identity.