Radio in the GDR

Radio and the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Before Reunification in 1990, the Germans lived in a divided land. A wall separated the country into the Federal Republic or FRG (Bundesrepublik; BRD) in the West, and the German Democratic Republic or GDR (Deutsche Demokratische Republik; DDR) in the East. And the topography of radio broadcasting was split into East and West too. After the Wall came down and the Cold War ended, GDR radio merged with stations in the Federal Republic to form a single broadcasting company for the whole of Germany. Today it’s known as Deutschlandfunk. Eva Sudrow worked in the DDR Rundfunk radio drama editing room in East Berlin, and later for Deutschlandfunk. She did radio for half the country, and subsequently for the whole country. Verena Hütter interviewed her.

By Verena Hütter

Ms Sudrow, what was your job at DDR Rundfunk?

Eva Sudrow: I was an assistant, office clerk, secretary – a general technician, you might say.

When did you start working at the radio station?

On 1st April 1976. In those days – back in the GDR era – we called ourselves the State Committee for Radio in the GDR. I was in the main radio drama department. And then came the end of the Cold War in 1990. Many colleagues were made redundant, only a few were left. At that point we were known as Funkhaus Berlin. Then the GDR broadcasters were combined to form a single radio broadcasting company, known as Deutschlandsender Kultur. It existed for two years under the umbrella of ZDF and ARD. And finally in 1994 Deutschlandradio Berlin was founded. This last radio station originating from the GDR era was merged with RIAS.

RIAS was Radio In the American Sector, which the Americans had established in West Berlin after the Second World War. And wasn’t there another broadcaster from Cologne too?

Deutschlandfunk from Cologne came into the mix as well. That station was responsible for the political information. Our broadcaster on the other hand was mainly culture oriented. Then in November 2015 I went into retirement. After almost 39 years working in radio.

In terms of complexity, an audio drama can be compared to a film production.

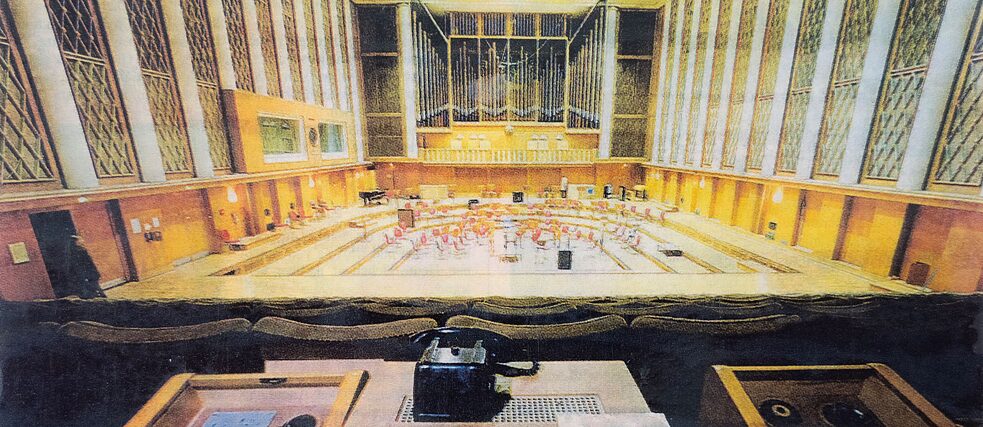

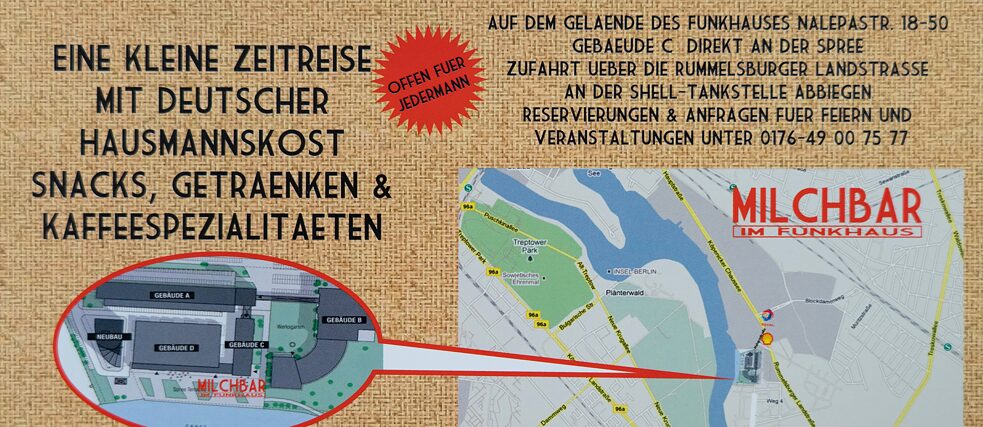

It wasn’t boring at all. I’ll describe my workplace in the former GDR radio studio for you, in Berlin’s Nalepastraße. Back then I worked on the production and broadcasting management team. Our department was responsible for production and transmission of radio dramas. In terms of complexity, an audio drama can be compared to a film production. Only without a camera. Instead of the cameraman, it was the sound engineer that was important to us. There was a high administrative burden. And all the organising jobs that needed to be done in relation to this, that was my remit.

My editorial department, radio drama, was responsible for the entire radio drama programme. We were not allocated to a specific station. We had various different stations that we worked for. They let us know their broadcasting slot, and then we had to fill it. We also produced international radio dramas, radio plays for children, and family series, for instance Neumann 2x klingeln (Neumann ring twice).

Who were the Neumanns?

It was a family comedy series about the life of the Neumann family. It was on once a week, and each episode lasted around 20 minutes.

Was it your dream job, getting into radio?

Not at all. I started out working at the foreign trade bank in Berlin. But they didn’t have any childcare places. By chance I discovered that they were looking for someone at Funkhaus Berlin, and they had childcare places. That’s how I got into radio, because of my children.

That’s lovely! Did you train as a bank clerk?

No, I started out as a shorthand typist and trained as a secretary. I improved my professional qualifications later on with additional diplomas. I’m trying to imagine the time when the Wall came down. You said that many people lost their jobs. But you were fortunate enough to stay?

It was a very unsettling time. There were investigations. They were in relation to state security. Whether you were somehow involved. There were checks. It wasn’t easy. It was nerve-wracking, waiting until the approval finally came. I have it in writing – in black and white – that I wasn’t an unofficial collaborator. [laughs]

The time when the Wall came down was rather precarious.

The fall of the Wall came as a great surprise for us. However there were a few signs. There was the great demonstration on 4th November 1989. Where the people rose up again. And before that the first political changes were starting with perestroika. Discussion was rife in the editorial team. In the radio drama department we had constant contact with artists and actors who came to the production from outside. They had their own unique perspectives and brought information. It was a rather precarious time.

And immediately after the Wall came down, they started screening the colleagues. Where they looked to see who had a clean slate and could stay.

There were around 3,000 of us employed there. It was like a small, well-organised town. There was even a healthcare centre, a variety of doctors. Everything was on site. And after the Wall fell, it all became increasingly sparse. More kept disappearing. That was sad.

How long did that phase continue? A year?

It was longer. It all kicked off from 1990, the trepidation and hope: who would stay? What will become of us? What will happen next? We were just one station from that point on, they didn’t need as many people now. Many people handed in their notice unprompted as well. I thought, hang in there. Either it works out or it doesn’t.

And after a few years you had survived it. It was certain that you could stay on. And then in 1994 there was another change …

… the merger with RIAS. In the GDR era, the GDR broadcasters and RIAS were polar opposites. They fought each other at a political level. RIAS had made it possible for GDR residents to listen to the station as well. Which of course as a young person, I did. RIAS was an interesting broadcaster, its programme appealed to me

They weren’t really interested in us.

There was some friction. It took a while for everyone to develop a good working relationship. To begin with, the colleagues from RIAS were sad that their station no longer existed as such. But we were the real losers.

You were the losers?

That’s how we expressed it at the time. We had this huge great studio in Nalepastraße, where there’d have been space for us all. But we had to relocate to another part of the city, to Hans-Rosenthal-Platz in Schöneberg, where RIAS was based. That was a political decision.

Can you remember what the biggest difference between the RIAS colleagues and yourselves was?

That’s difficult to answer. Actually they were friendly and nice. From time to time something was said that made us realise: they didn’t know much about us. In the West they had their ideal world, where everything was perfect. They weren’t really interested in us. That was how I perceived it.

They still put on radio plays from a long time ago.

I wouldn’t say that. A radio play is a radio play. It just depends on the content. What the authors have written, and what the editors make of that. With some GDR radio plays they said after the end of the Cold War: we can’t put this on anymore. But there are lots of other radio plays from the DDR collection that they still broadcast after the end of the Cold War as well. They scheduled a special programme slot for it. It fitted in well.

Do you still listen to the radio?

I still listen to the radio a lot. Regional radio and Deutschlandfunk.

Can you still find a little piece of your station from the GDR era in Deutschlandfunk as it is today?

Yes, of course. I check that every day. [laughs] I have the listings magazine delivered. And I look to see what radio plays are on, and when they were produced. They still put on plays from a long time ago, in which I was involved.

A huge thank you goes to Eva Sudrow for sharing her memories, as well as to Nathalie Singer for the idea and arranging the interview. <3 <3 <3