Coding da Vinci

The digitalisation of culture

Visitors to museums and archives usually interact with exhibits locked in display cases in darkened rooms. Yet modern technology has given us ways to more directly experience art and cultural artefacts. Coding da Vinci is an open, cultural data hackathon that digitally brings museum pieces to life.

Von Eva-Maria Verfürth

Conventional museums rely on the power of visitors’ imaginations. Since valuable and fragile objects cannot be touched or tried out, viewers have to envision what they might feel like or how they might have been used. Texts and information are presented as vividly as possible, yet museum goers still have to recreate events as they might have been in their minds. Now a cultural hackathon project is showing just how technology can be used to make GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) collections tangible and digitally reconstructing historical spaces.

Slipping on the functional suit at the “Kleid-er-leben” (Experiencing Clothes) VR exhibit gives visitors a very real sense of how just how restrictive the clothing of past centuries on display in the Historisches Museum Frankfurt was. Users select something to try on, and can then walk through virtual historical spaces and look at themselves in a mirror. The mobile RingRing game brings the historical telephones in the Museum Foundation Post and Telecommunication’s collections back to life. Although silent and motionless on the shelf, the museum pieces ring in the app as the user works to match the right ring tone to each phone. The “Altpapier” (Wastepaper) app compiles the most bizarre newspaper reports from the early 20th century for political fun, combining entertainment and historical education in one and available everywhere via smartphone and the internet.

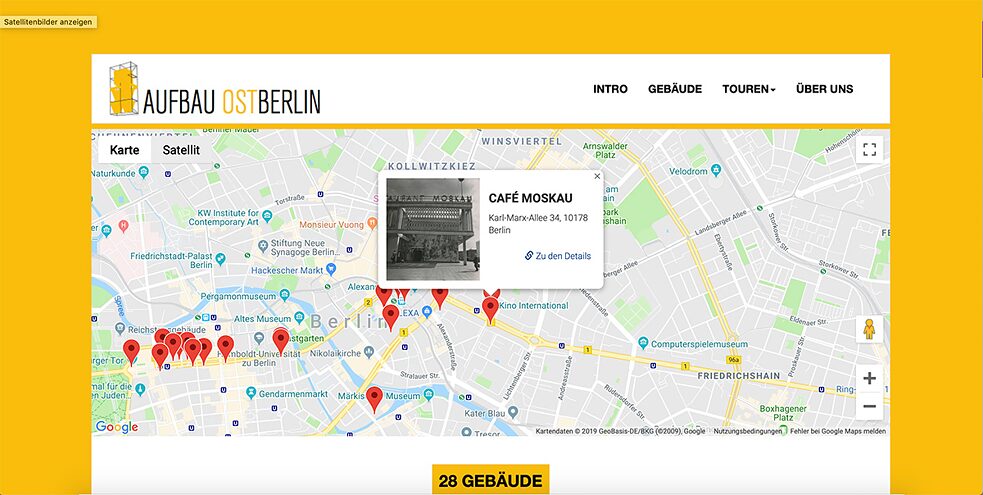

Even the Berlin Wall, most of which was torn down decades ago, can be rebuilt in the virtual realm. Coders have taken the archive of the “Stiftung Berliner Mauer” (Berlin Wall Foundation) to the streets. Visitors to the capital can download the “Berliner MauAR” app to view the Berlin Wall on screen right where it used to divide the city, and even walk around it. The app uses a smartphone’s GPS localization to display historical images of right where the user is standing. A visit to the “Aufbau Ost-Berlin” (Rebuilding East Berlin) website shows how the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany) government imagined the capital’s future. The website and mobile application suggest tours on various topics and displays the respective GDR vision at each location.

From a tourism app to a robot beetle: screenshots and pictures of the projects created by Coding da Vinci.

| Photo: © Coding da Vinci

From a tourism app to a robot beetle: screenshots and pictures of the projects created by Coding da Vinci.

| Photo: © Coding da Vinci

More than a dozen new projects in just six weeks

All these digital applications make knowledge more accessible, more descriptive and also more entertaining. So it might come as a surprise that they are not the results of long, costly large-scale projects: all were created in no more than six weeks during Coding da Vinci, an open, cultural data hackathon. The event brings cultural institutions and technology experts from different sectors together to develop new ideas for cultural mediation - without a commercial agenda and restricted to a set project period.The fact that completely new applications can be created in such a short time is mainly because a treasure trove of resources has been available for quite a while now. Most cultural institutions have digitized their collections, and many GLAMs have created digital databases to safeguard and catalogue their collections. Their servers store vast quantities of valuable data ranging from high-resolution copies of paintings and historical sound files to 3D scans of dinosaur skeletons. The hackathon is a way to put the existing date to good use by repurposing it.

The first cultural hackathon took place in 2014, and was backed by cultural and open-data organizations including the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (DDB, German Digital Library), the Forschungs- und Kompetenzzentrum Digitalisierung Berlin (digiS, Research and Competency Centre Digitalization Berlin), the Open Knowledge Foundation Deutschland and Wikimedia Deutschland. Since then it has been held once or twice a year at different locations in Germany, and the Federal Cultural Foundation has agreed to fund an additional eight hackathons from 2019 to 2022. Each Coding da Vinci opens with an introductory workshop where participating cultural institutions present their data collections. Interdisciplinary teams of designers, developers, graphic designers, museum curators, artists, hackers and game developers then brainstorm project ideas for apps, games, visual infographics and more. The six-week work phase is devoted to realizing the best ideas, and the data is transformed into more than a dozen completely new products in just a few weeks.

Leveraging the potential of culture

The organizers of Coding da Vinci hope their event encourages GLAMs to open their digitized collections to the public, reasoning that: “If they were created with public funds, they should be freely available to everyone.” Additionally a large percentage of a GLAM’s collection is kept in storerooms where the general public may not even be aware of them. The organizers of Coding da Vinci feel digital access could change this, and inspire a whole new level of enthusiasm for culture and museums in a young audience of digital natives. It is going to take more data to reach this goal. Based on the photographs of Gisela Dutschmann, who captured the reconstruction of East Berlin with her camera, the team members of “Aufbau Ost-Berlin” have created digital city tours.

| Photo: Screensthot © Aufbau Ost-Berlin

From a technical standpoint, opening digital collections to the public would not be particularly difficult. But many in the GLAM space are reluctant to do so, fearing that the data could be misused or commercialized. Here Elisabeth Klein, project coordinator of Coding da Vinci Rhine-Main, sees another hackathon objective. She hopes a space where GLAM representatives can network with the hacker community and get in touch with programmers and creative minds while exploring the range of different projects that could emerge from open data could reduce fears of a loss of control.

Based on the photographs of Gisela Dutschmann, who captured the reconstruction of East Berlin with her camera, the team members of “Aufbau Ost-Berlin” have created digital city tours.

| Photo: Screensthot © Aufbau Ost-Berlin

From a technical standpoint, opening digital collections to the public would not be particularly difficult. But many in the GLAM space are reluctant to do so, fearing that the data could be misused or commercialized. Here Elisabeth Klein, project coordinator of Coding da Vinci Rhine-Main, sees another hackathon objective. She hopes a space where GLAM representatives can network with the hacker community and get in touch with programmers and creative minds while exploring the range of different projects that could emerge from open data could reduce fears of a loss of control. Ruth Rosenberger from Bonner Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (the Bonn House of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany) raves about Coding da Vinci. “I am always really impressed by the exceptional projects. It was exciting to work with a young, interdisciplinary team that took a fresh look at the photos from our collection. A modern museum has to establish itself on the net. [...] The cultural hackathon helps us to discover new ways to do so.”