Stereotypes

The Fine Art of German Nachhaltigkeit

Germans made headlines in the past as pioneers of recycling, photovoltaic technology and resistance to nuclear energy production, and still today they are proud of their ecological mindset. Yet signalling being nachhaltig is sometimes easier than actually being it.

Von Adam Fletcher

Germany is a country that thinks green, tries to act green, and where quite a few of its citizens even vote Green: This is what every travel guide will teach you, and many Germans – who like to uphold their own stereotypes – will most probably as well. Demonstrating their environmental awareness is well entrenched in their everyday life, as every foreigner will experience in the first days or even hours spent in the country. I will tell you about my first lessons on the importance of German Nachhaltigkeit.

German Mülltrennung

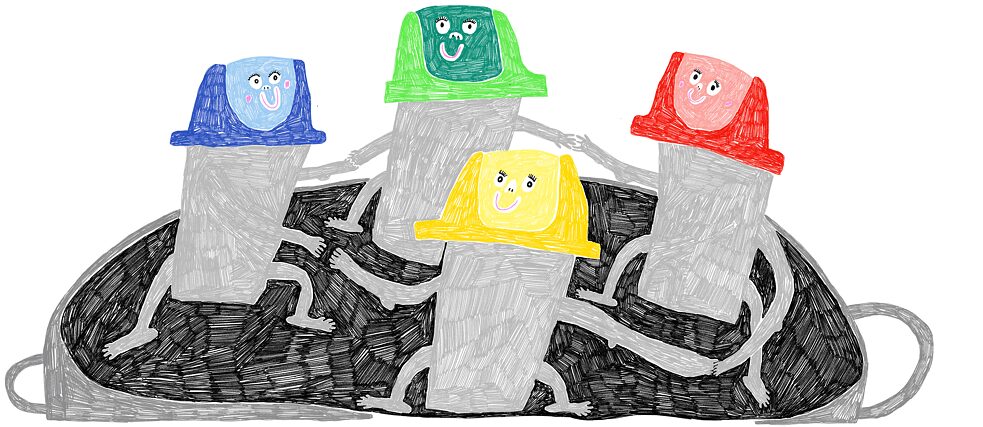

It was my first Arbeitstag, my first working day in Leipzig, Germany. We’d just finished eating in the company kitchen. I got up off my stool holding an empty salt and vinegar crisp packet in my hand, because I am British, and lunch is not lunch unless I have put thinly fried potato in my mouth and crumbed all over myself. I was met by an extraordinary number of bins, all wearing different coloured hats. I looked down at the packet and felt like I was playing an unsexy Escape Game. What bin…?I yanked the lid off the black bin and dropped in the crisp packet. An arctic frost blew into the room, all conversation hushed. I turned my head slowly. “What?” There was a silent meeting of eyes: who was going to step up and educate this ignorant about the finer art of German Nachhaltigkeit? My boss, Andreas, decided it would be him. “Plastic goes in the yellow bin,” he said and removed the lid. Inside, a heap of neatly pre-washed plastic cuddled. “Oh,” I said. “Is it important? Do I need to take it out of the other bin, I mean?”

“Probably best,” he said diplomatically. I removed my packet. “It’s really very simple.” He pointed. “This one is bio. This one is glass. Then paper, of course. This one is other, but we only use that in emergencies. You don’t have four bins in England…?”

Germans are passionate recyclers. It combines three of their favourite things into one, earth positive activity – environmentalism, hyper organisation, and anal retentiveness. Try putting something made of paper in your German friend’s plastic bin and it will trigger alarms. Keep that in mind if you want to avoid conflict with your colleagues, flatmates or parents-in-law: you better know how to sort and divide correctly.

But that’s not their only sustainability passion.

Germans are passionate recyclers.

| Photo (detail): © Susi Bumms

Germans are passionate recyclers.

| Photo (detail): © Susi Bumms

Bio Bio

In Germany there’s a love of all things Bio (organic). Germans have whole supermarkets dedicated to organic products. If you want to sell anything in this country, slap the word bio on it. Bionade, for example, a fizzy lemonade made of organic ingredients that is very popular in Germany. I always found its taste boring – until I realised they weren’t drinking it for its taste. The taste was incidental. They were drinking it because they have a built-in, must-buy reflex when confronted with any product labelled bio. Bionade had simply found a hack to popularity.

Flaschefishing

And then there’s the country’s great Pfand system on bottles, reportedly the largest and most successful in the world, with a 98 per cent return rate. I remember on my first day in the country, at a kebab restaurant, when I brought my empty plate and glass bottle back to the counter, not wanting to make a mess, and the man gave me a tiny coin and I thought, I’ve won the world’s worst lottery. I immediately looked around for more bottles. I’ve never stopped looking. Flaschefishing I call it. I’m not the only who does it. At least one person per day comes into our courtyard in Berlin, picking it clean of our empties. Live here a while and you wonder why all countries don’t have a scheme like this? They should.

Kohle Und Atomkraft? Nein Danke.

Then there’s this big nationwide Energiewende project. Since 2000, Germany has spent a staggering €500 billion on a programme trying to replace fossil fuels and nuclear power with wind and solar energy, much of it from their own technology. After all, green tech is 15 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product. The entire nation aims to be climate neutral by 2045. Will it live up to these promises? It’s hard to say. These changes are big. And signalling you are nachhaltig is easier than actually being it. You will probably have German friends who exclusively wear hemp, wax lyrical about homeopathy, recycle fastidiously, only buy organic chicken from Biomarkt, yet overlook how they drive there in their diesel car (with an Atomkraft? Nein Danke sticker on the rear window), fly eight times a year and eat meat five days a week in the office canteen, an office they probably would cycle to if the government of this supposedly green land cared enough to build the infrastructure they would need to do so safely.

Don’t point these hypocrisies out; every culture has them; Germany is trying.

This Is Germany.

Now, do you want to know how the story of my first Arbeitstag in Leipzig went on? During our conversation about sorting rubbish in the office canteen, the cleaner, Frau Krump appeared. “It’s all combined into one big bin downstairs, anyway,” she muttered. My boss Andreas’ knees buckled. There was a loud “Wie bitte?” (What the…?) from someone.

“They just combine them all downstairs?” Andreas asked in disbelief.

“Yes.”

Now, you would think, armed with the knowledge our recycling efforts were for futile, liberated from the burden of having to categorise and sort and divide, we tossed everything in the big black bin from then on, right?

Wrong.

Nothing changed. Actually, if anything, we sorted and recycled harder from then on. We had to make it clear we were not the problem. The problem was downstairs. We were doing our bit. We’re part of the solution. It’s not our fault, Alaska. Don’t hate us, Polar Bear. We recycle whether or not it matters, because that’s what you do. That’s who we are.

This is Germany.