Culture in the Quarter

Making van Gogh and Inside Rembrandt

Two exhibitions on classical masters are running simultaneously in Frankfurt and Cologne: “Inside Rembrandt” and “Making Van Gogh” provide exciting insights into the history of art and how great artists emerge. In addition to some of the two painters’ best-known works, the exhibitions also feature many unknown pieces from each artist’s circle.

By Andreas Platthaus

It is a remarkable coincidence that two of the most spectacular art exhibitions in German museums opened in late autumn with English titles. Making Van Gogh at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main and Inside Rembrandt at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne have brought the work of classical grandmasters to German museums. The titles may have been chosen to attract the international audience that flocks to both cities, attractive tourist destinations in which English has long been the lingua franca.

The Cologne museum was established in 1824, and the Frankfurt museum can trace its history all the way back to 1816, making them two of Germany’s oldest state museums rich in tradition. Both are well regarded and have a lot to offer international exhibits from their holdings. In the recent past, the two museums have skilfully leveraged their art-based bargaining power and honed their befitting international reputations with exceptionally well-assembled special exhibitions. The Van Gogh and Rembrandt shows are the next chapters in their success stories.

But despite the museums’ excellent reputations and the adept negotiating skills, exhibitions featuring a single, celebrated artist are prohibitively expensive, making them almost impossible to pull off. So the museums opted for a somewhat different approach, and one that is charming in its own right.

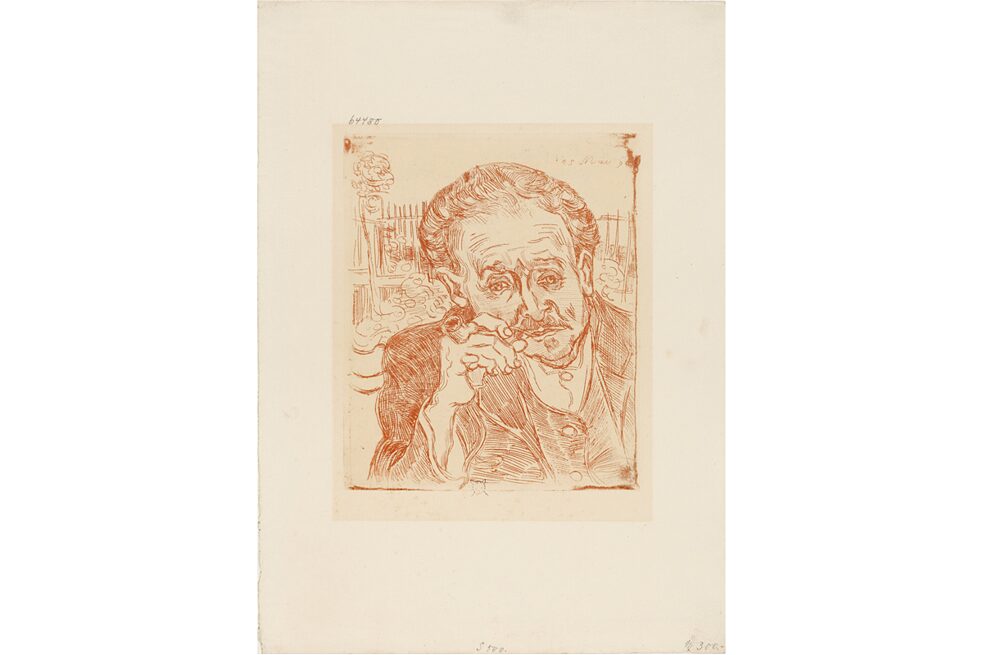

Beyond Rembrandt and Van Gogh

Rembrandt and Van Gogh number among the most famous artists in the world, which makes it harder to borrow their work from other collections. Their paintings are in high demand around the globe, and key visitor attractions at their respective home galleries. Additionally, insurance coverage is enormously pricy, running to the billions for the Frankfurt Van Gogh show with almost fifty works by the master himself. Interestingly, over half of the paintings on display are not even by Van Gogh. Of the 110 pieces on exhibit in Cologne, only thirteen were painted by Rembrandt and a few of his etchings are available to the viewing public as well. The majority of the pieces included in both shows were not actually done by the artist who lent the exhibit his name, and whose lasting fame is drawing crowds.

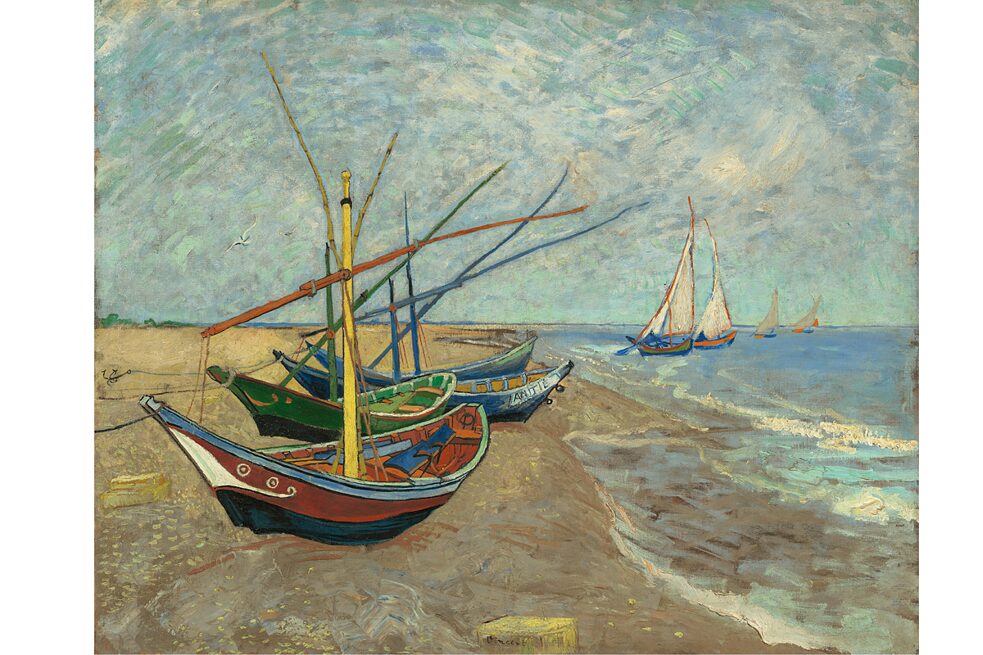

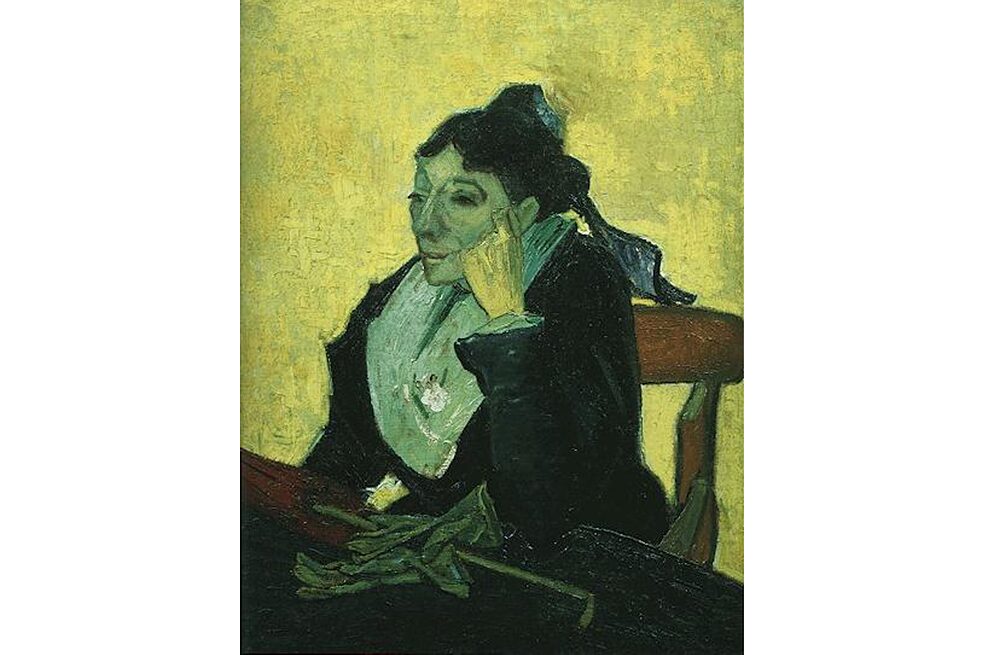

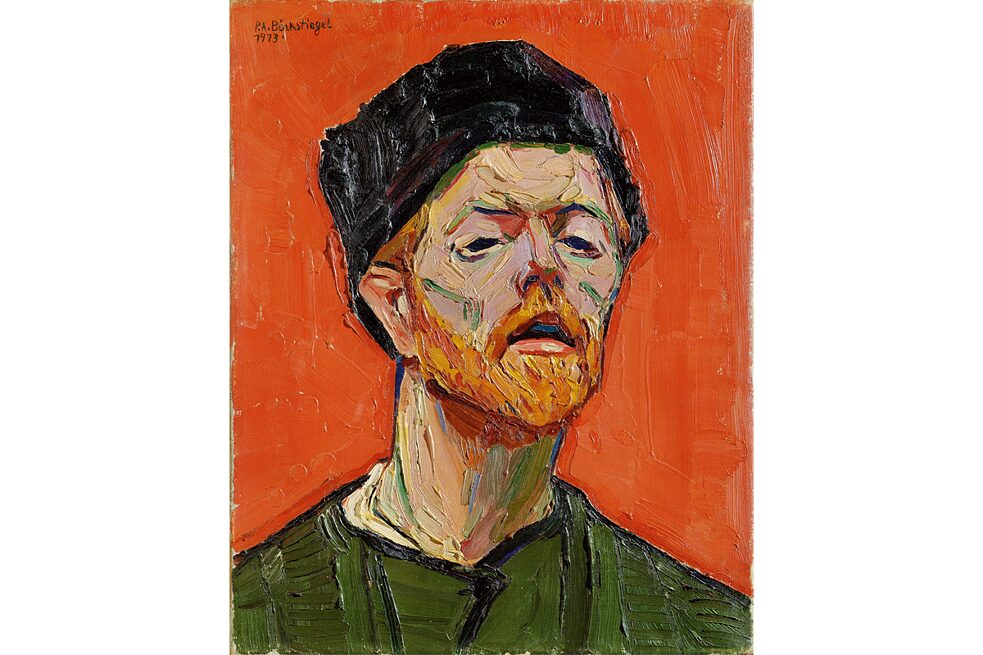

Making Van Gogh and Inside Rembrandt are cleverly chosen names that evoke a special sense of intimacy that conceals this discrepancy between advertising and reality. The suggestive exclusivity of the materials on display gives visitors the impression they will be taking a deep dive “inside” Rembrandt and watching as Van Gogh is “made”. Only direct interaction with the exhibit allows visitors to decode the titles as euphemisms for a trip into the art history studio, rather than a peek at the masters’ activities and inner lives. Inside Rembrandt uses a large number of paintings from other artists of the Golden Age to illuminate the business model used by the painter and those who mimicked his style. Making Van Gogh includes many works by German painters of the time to document how enthusiastically the artist was received in Germany at the start of the twentieth century. This approach plays to the Städel’s strengths, which include a rich collection of early 20th century German painters and only one, relatively insignificant Van Gogh.

To prevent any misunderstandings though, it must be said that both exhibitions are exceptionally well-arranged from a didactic standpoint, and include some truly spectacular objects, especially among those not attributable to their namesakes. Inside Rembrandt houses a small Jan Lievens exhibition that impressively highlights the skills of Rembrandt’s early friend and later rival. The clever arrangement of the few Rembrandt paintings in Cologne reveals a close connection to paintings from other brushes, , opening up a point of access to the core of what constitutes the Rembrandt myth. Cologne and Frankfurt both followed the same method, choosing to focus on the emergence of a universally popular brand name and all the phenomena that surround it, like marketing, imitation and even forgery.

Famous paintings draw crowds

And though not all the paintings were done by the eponymous artists, both museums have succeeded in bringing some spectacular masterpieces to their cities. The Frankfurt Museum once owned one of Van Gogh’s key works: the Portrait of Doctor Gachet. In 1937, however, National Socialist art policy declared it “degenerate” and forced the museum to relinquish it. Now the Städel is drawing in visitors with another international sensation: Van Gogh’s only slightly less heralded Arlésienne on loan from Musée de Quay d'Orsay in Paris. This coup probably drew many other paintings to Frankfurt in hopes that their status would be enhanced through the close proximity to the famous Arlésienne.

A painting from the Prague National Gallery plays a similar role in the Cologne exhibition: Rembrandt’s Scholar in His Study. This is the only the second time it has been on display in another country. The mere fact that the painting was lent to the Wallraf-Richartz Museum is an extraordinary event. It will also benefit from its juxtaposition with another highly significant Rembrandt painting the museum owns, namely Self-Portrait as Zeuxis. It will make the trip to Prague next year, where the same exhibition will open its doors to the public there.

Cologne curators seem to have scoured Easter European museums quite thoroughly and secured a number of loans from them. These are lesser-known masterpieces because their home galleries are less frequented than their larger brethren in Western Europe or North America. But this only enhances the allure of interacting with these paintings. The Frankfurt exhibition holds many fewer surprises, since the works on loan are mainly from the Netherlands and France.

From outsider to grandmaster

That these two exhibitions are running at almost the same time is remarkable in itself: taken together, they beautifully illustrate a general principle of art history: the rise of the aesthetic outsider to a dominant position as a grandmaster who shapes an entire school. This process has rarely been traced as subtly as at the Städel and Wallraf-Richartz museums right now. In combination, these exhibitions offer much more than just the sum of their parts.