Masculinity

When Is a Man a Man?

What does being a man mean? We have asked a few people in Germany what masculinity means to them.

By Sonja Eismann

Masculinity is going through a crisis. At least, that is the way it seems if you look at how concepts of masculinity have been reported on and discussed over the last few years. There was much talk of outdated role models, of man as the loser in these times of modernisation, of toxic – i.e. violent, harmful – masculinity, even of the end of male dominance and the advent of a “Golden Matriarchy”. We wanted to know from very different people in Germany, what masculinity means to them and what ideals they are hoping for in the future.

Max Kade (19) graduated from high school in Bamberg and is currently taking a preparatory art course in Leipzig.

For me, the differences between male and female do not play a major role. I find it wrong to use physical features such as vulva or penis to determine a person’s sex, especially since I think there are more than two genders. My concept of role models was certainly influenced by my parents who tried to educate me and my younger sister beyond these gender norms, although of course they are not completely free of them themselves. When I think of male ideals, I tend to think of negative concepts like toxic masculinity. I find it positive, if someone projects an image of masculine strength, but can still be emotionally open. For the future, I suspect that binary gender roles will continue to fade away, which makes me happy. But capitalism will probably not lead to the abolition of patriarchy, even if I would like it to.

Anas Mardikhi came to Germany from Syria a few years ago and is currently taking a course to get his licence to become a pharmacist in Stuttgart.

The ideal man is a helpful man. He knows what his friends need and always tries to be there for them. His appearance, his body or his clothes are completely irrelevant. It all depends on his inner being, on his heart. The perfect man always thinks positively and tries to make or solve problems instead of wallowing in the bad. I believe that differences between different countries or cultures are much less important than family and education. If I ever have a son, I will definitely tell him to think positively.

Elke Schubert (76) is very much involved in the family business and local politics. She lives with her family - three children, five grandchildren - in a village in the south of the state of Hesse.

Masculinity was not an important factor in my marriage. When we were raising our three children, however, there were situations in which the necessary order could only be restored by my husband putting his foot down. A loving father, who cuddles, has fun and plays with the children, is in my eyes more masculine than an ever grumbling and punitive father. Of course, masculinity is also related to outward appearances - if a man with a beer belly and his undershirt hanging out does not lift a finger to help the family, but would rather slouch in front of the TV or computer after work, then this, for me, is unmanly. A sporty, well-built man, who also attaches importance to a modern look, is in my eyes the masculine type. I also find it important that it is good for a woman in an equal partnership to have a male shoulder to cry on in stress situations.

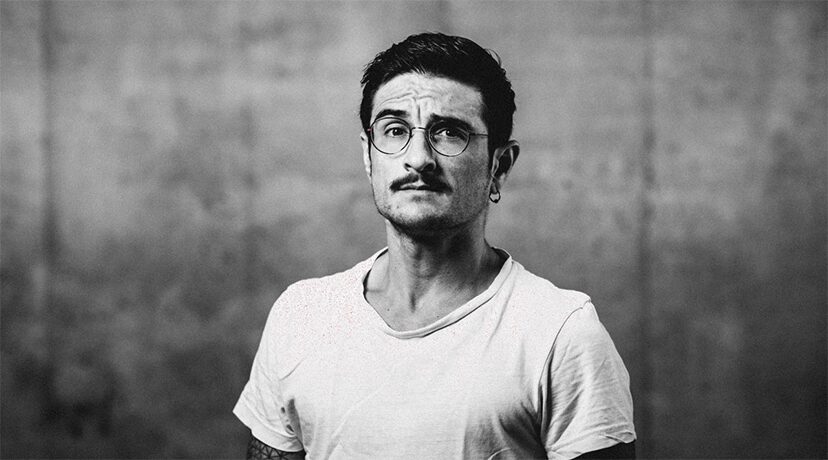

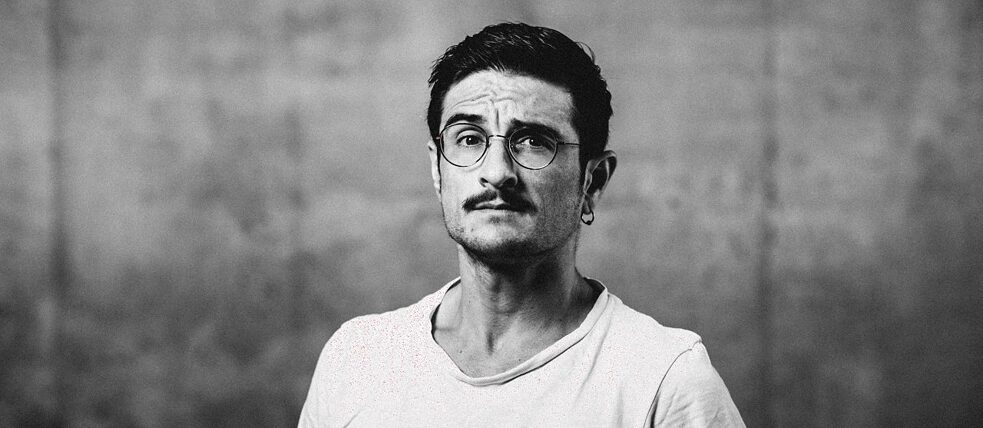

János Erkens (35) is a press officer and freelance journalist in Frankfurt am Main.

Someone like me really ought to know best what masculinity is. Because unlike a man who was born as a man, I had to convince quite a few people that I was really a man. In fact, I cannot tell you what is masculine about me - except the certainty that I am a man. My friends say that I have only changed externally through gender alignment. In the past I was perceived as a woman without any confusion, now without any confusion as a man. Unfortunately, I do not know what that says about masculinity.

Raul Krauthausen (39) is an inclusion activist, author and presenter living in Berlin.

I have relatively little in common with the male ideal or cliché. Not only because I’m disabled, but also because I’m small. And because I am in a wheelchair I do not fit in with the image of the protector, but rather with that of the one that needs protecting. In my youth I felt unmanly. It soon became very clear to me that I was not at the top of anyone’s list when it came to cuddling at teenage parties. This meant I could see the whole thing in a more differentiated way. I questioned who was considered to be really strong, and found that it could also be about emotional strength. Men are probably the weaker sex because they suppress this. I have distanced myself from the classical concept of masculinity and try to allow the female side in me to come out, to even weep sometimes, too. In principle, I would like all men to recognise privileges and use them to make space for the non-privileged.

Tharsana Tharmalingam (45) lives as a working, single mother with her nine-year-old daughter in Berlin.

I have always been afraid of men. Of their dominating character, of their violence. It took a long time for me to get involved in any relationship at all. I question everything that society still expects of women today: living with a man, getting married, raising children together. The point is I live for myself, not for society. Even with supposedly progressively thinking men, I see that their feminism often exists only in theory. I do not want a person’s sex to matter, but we’re still a long way from that. And that is why I believe that it is really men, not women, who need empowerment. So that they will finally no longer be afraid of us - and that the mentality of witch burning will disappear forever.