Worlds of Homelessness

Informal Studio

A teaching experiment from Johannesburg bringing together formal and informal housing processes. The [in]formal Studio transplants academic training into real-life situations of informal urbanism, engaging in partnerships with residents as active agents of development. Developed by 26’10 south Architects at the University of Johannesburg these courses represent the culmination of the ‘Housing and the Informal City’, a research project by 26’10 south Architects in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut, Johannesburg.

By Thorsten Deckler

Founded in 1886 when gold was discovered on a savannah plateau, Johannesburg quickly grew into an economic powerhouse on the African continent. Under Apartheid the city was strictly segregated according to race and eventually isolated from the world through global sanctions. With the advent of democracy in 1994, Johannesburg once again became an economic magnet for people from Africa and beyond and now, 25 years into democracy, it is known as the creative capital of the southern hemisphere. It is also known as one of the world’s most unequal cities and it is where we live and work as architects.

Here the lack of public safety, decent schooling, housing and healthcare have presented amazing opportunities for the private sector with architecture used as a tool for sanitizing and securing the urban landscape for a few who can afford it. Despite ambitious upgrades of poorer neighborhoods, the beginnings of a public transportation system and the building of thousands of subsidized houses, the template laid down during Apartheid persists, leaving many citizens to their own devices in meeting their basic needs, including housing. In South Africa, a backlog of 2.3 million houses (Stats SA 2012) has resulted in people building their own homes and neighborhoods. Yet the formal system in which we have been trained as architects condemns these self-made homes as illegal. Africa is home to ten of the fastest-growing cities in the world and it is estimated that 75% of urbanization will be informal.

Change cannot be conjured without suspending judgment of the perceived problem.

An aspect of the InformalStudio distinguishing it from many design and build initiatives led by visiting architecture schools is that it does not assume to be delivering development (usually in the form of a building), but rather on supporting a people-driven development process. The question of who is ’the’ expert was challenged early on and established a fundamental shift that acknowledged residents as legitimate partners and experts of their lived reality. This helped to mutually set a teaching agenda that balanced the learning outcomes for students and staff with generating useful outcomes to support each particular settlement.

Two seven week courses were held in Ruimsig (in 2011) and in Marlboro South (2012) respectively. The main output of each course was the mapping of a hitherto ‘unseen’ urban reality. These mappings became practical planning tools for residents, but also tools of agency enabling residents to speak the language of city planners and partake in the decisions affecting them.

The two courses are briefly summarized below:

Informal Studio: Ruimsig

Residents of Ruimsig, a small informal settlement west of Johannesburg, had just completed a self-enumeration and required an accurate map of their settlement. Through the studio students and residents produced this map and also a re-blocking strategy which outlined proposals for immediate improvements which could be undertaken by residents themselves. The main objectives of re-blocking are: the equitable distribution of land, addressing overcrowding and the activities of slumlords; the adjustment of movement routes to suitable road widths for improved circulation and passage of emergency vehicles and the eventual introduction of services. Re-blocking is motivated by minimal physical adjustments, thus respecting the organic logic of how people first settled the land.After the course, residents, assisted by NGOs systematically began to tackle the physical upgrading of their surroundings, moving houses and fences and re-settling households from congested land and flood lines into better positions. This involved protracted discussions amongst residents themselves which were not always benign, yet were guided by the SDI methodology and with an achievable outcome insight.

Through the association with the university and the production of a re-blocking plan, Ruimsig has received increased attention from city authorities who even declared the area an ‘experimental zone’ in which certain municipal standards and by-laws may be re-defined in order to meet the spatial demands of the settlement. The effects of this have been a sense of security of tenure which has visibly manifest in improvements people have made to their homes and gardens. Perhaps most powerful, for us as architects, is the idea that an informal settlement is simply a young city growing up and the question is what do its inhabitants actually need to thrive? Even Manhattan started as an informally settled trading post!

Re-blocking map drawn by T. Deckler and A. Opper based on group proposals made during course | © 26’10 south Architects

© 2011/ 2012, Architects' Collective and respective authors. All rights reserved.

Informal Studio: Marlboro South

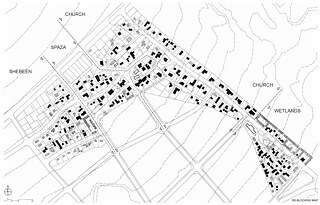

In 2012 the studio was invited to work in Marlboro South, an industrial buffer strip implemented during Apartheid to separate Alexandra, one of Johannesburg’s oldest black townships, from its more affluent white neighbors. Over the past three decades approximately 1,500 mostly poor black households moved into the area in order to benefit from its central location. In the process highly organized communities established themselves in abandoned factories and warehouses making do with municipal services and living under the constant threat of eviction.

Conclusion

Working in the InformalStudios has taught us, as architects, a number of things. That change cannot be conjured without suspending judgment of the perceived problem. We have learned that the problem contains the solution, but that it is hidden, firstly through our privileged outrage at the unfairness of the situation and secondly through our education as ‘experts’ of a narrow field. We have learned that working in complex situations requires crossing the boundaries that define our expertise and to bring together different experiences, insights and readings of the city. An example that best illustrates this comes from a subsequent workshop on upgrading held in East London, South Africa where various built environment professionals sat around a table together with the informal mayor of a small settlement occupying an area reserved for stormwater run-off. Much of the discussion circled on what is the role of a road? Why is it taking up so much space? Is it for cars, ambulances and firetrucks? Is it to manage stormwater? Is it to distribute services? Is it a public space?The answer is, of course, all of the above and more.

Similarly, we can ask what is a home? Is it a bolt hole to access the city economy? Can it be shared? If it is too small, can the city provide the rest? Is home in an entirely different city or even country? Can a home be a shop, factory or office? Why can’t it be built with my own hands?

Working in Johannesburg has made us acutely aware of the limits of our influence in undoing deep structural damage. Working in the InformalStudio with over a hundred collaborators and as part of a network of thousands more has revealed to us a new power that lies in observing, engaging and collaborating – not to fix a problem but to lean into it and discover already existing systems that contain the answers we are looking for.

The studio was, however, only made possible by the contribution and commitment of over a hundred other lecturers, students, residents of Ruimsig and Marlboro South, city officials as well as members of the Shack Dwellers International Alliance and their member organizations.