The portrait of the lawyer Hugo Simons

German Traces in Montreal

The Portrait of the Lawyer Hugo Simons

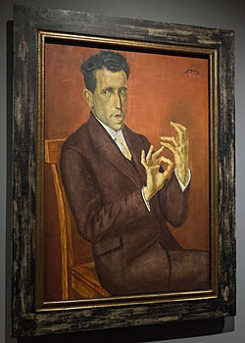

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal) houses an extraordinary treasure in its collection: a portrait of the artist Otto Dix’s lawyer and friend Hugo Simons (1892-1958), which was painted in 1925 in Germany. This piece has three features of particular interest: the unusual painting technique that Dix used for this portrait; the origin story of the work; and its odyssey during the Second World War, from Nazi Germany through Holland to Montreal.

Otto Dix (1891-1969) is undoubtedly one of the most significant modern German painters. His high rank in the international art scene is thanks to his expressionist drawings, gouaches, and oil paintings from before and after World War I, totaling over 600 pieces. He came to fame as part of the Weimar Republic’s “New Objectivity” (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement in the 20s. As a big admirer of northern European Renaissance painters of the 16th century, such as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Baldung Grien, or Hans Holbein, Dix studied the themes and painting techniques of the old masters carefully, often incorporating them into his work. As a result, he gained a prominent status among his artistic colleagues in the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, like George Grosz or Max Beckmann.

The portrait of Hugo Simons in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, painted by Otto Dix

| © Goethe-Institut Montreal

The portrait of the lawyer Hugo Simons, effectively a textbook example of this style, was painted with egg tempera colours in accordance with medieval techniques. This lends the work a special kind of “aura”, to borrow a phrase from Walter Benjamin. Many of Otto Dix’s works – particularly those from the Neue Sachlichkeit period – were either sold or destroyed by the Nazis, so the paintings that still exist from this era are very valuable due to their scarcity, especially from an art history perspective.

The portrait of Hugo Simons in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, painted by Otto Dix

| © Goethe-Institut Montreal

The portrait of the lawyer Hugo Simons, effectively a textbook example of this style, was painted with egg tempera colours in accordance with medieval techniques. This lends the work a special kind of “aura”, to borrow a phrase from Walter Benjamin. Many of Otto Dix’s works – particularly those from the Neue Sachlichkeit period – were either sold or destroyed by the Nazis, so the paintings that still exist from this era are very valuable due to their scarcity, especially from an art history perspective.

Dix painted Hugo Simons’ portrait in 1925 because he was thankful to the lawyer, who had successfully represented him in a lawsuit. Shortly beforehand, a client had asked Dix to paint a portrait of the client’s daughter. However, upon completion of the painting, the client refused to pay for the portrait, claiming that it didn’t look anything like his daughter. The case, which had a happy outcome for Dix, was not only a milestone in the official recognition of artistic freedoms, but was also the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the painter and his lawyer/model. The two became pen pals, even though their relationship was limited by the confusion and hardships of the Second World War.

Dix remained in Germany, where he was hit hard by the power of the Nazis, who banned him from teaching and exhibiting his work. He moved to a small town near Lake Constance (called Bodensee in German) on the Swiss border, where he spent the war and the years immediately following it unemployed and in poverty. Meanwhile, Hugo Simons fled Germany in 1933 with his family and possessions, going to The Hague in Holland. Simons was stateless and without a work permit, but he and his wife dedicated themselves to helping German Jews escape to Holland with great success. In 1939, after much difficulty, they were finally able to get passage to Canada with their three children. The family settled in Montreal, where Hugo Simons supported himself and his family with assorted jobs until his death from cancer in 1958.

Panel to the painting

| © Goethe-Institut Montreal

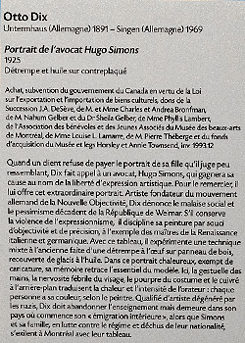

The Dix portrait of Hugo Simons, which had also made the journey to Canada, was first displayed publicly in 1964 as part of an exhibition of the Simons collection at the Goethe Haus Montreal. This was followed by several exhibitions in Germany and England in ‘91 and ’92, and Hugo Simons’ children eventually decided to leave the painting to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts on loan. However, the growing popularity and value of the painting brought the Canadian tax authorities into the picture. The Canada Revenue Agency demanded that the family pay capital income taxes for the painting from 1972 to 1992 in arrears, which effectively forced them to sell the piece. An American art dealer offered to buy the painting at its appraised value of 1,650,000 USD, but the Simons family instead offered the painting to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts for 810,000 CAD, a discount of over 50%. They wanted to thank Canada for accepting them in 1939 and to ensure that the picture stayed in Montreal. After subsequent negotiations and a tug-of-war on the financing of the acquisition between the museum, federal and provincial governments, and private financiers and patrons, the painting could finally be integrated into the Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection in the summer of 1993.

Panel to the painting

| © Goethe-Institut Montreal

The Dix portrait of Hugo Simons, which had also made the journey to Canada, was first displayed publicly in 1964 as part of an exhibition of the Simons collection at the Goethe Haus Montreal. This was followed by several exhibitions in Germany and England in ‘91 and ’92, and Hugo Simons’ children eventually decided to leave the painting to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts on loan. However, the growing popularity and value of the painting brought the Canadian tax authorities into the picture. The Canada Revenue Agency demanded that the family pay capital income taxes for the painting from 1972 to 1992 in arrears, which effectively forced them to sell the piece. An American art dealer offered to buy the painting at its appraised value of 1,650,000 USD, but the Simons family instead offered the painting to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts for 810,000 CAD, a discount of over 50%. They wanted to thank Canada for accepting them in 1939 and to ensure that the picture stayed in Montreal. After subsequent negotiations and a tug-of-war on the financing of the acquisition between the museum, federal and provincial governments, and private financiers and patrons, the painting could finally be integrated into the Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection in the summer of 1993.

On your next visit to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, please don’t miss out on seeing this unique piece in person with its incredible story.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

1380 Rue Sherbrooke Ouest

Montréal, QC H3G 1J5