As a new genre, media art promised women artists that they would be able to break free from the art scene’s established gender roles. But they were soon forced to realize that a new direction in art does not automatically bring new social structures with it. It became apparent that in the web as well, women artists were exhibited and invited less.

Many more recent works of feminist media art directly or indirectly reference traditions of the video- and performance-art of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Others repeat their methods and structures in the attempt to question gender attributions. Many works treat the theme of corporeality and digital disembodiment – and in doing so advance the conversation.

from seeing to feeling

Austrian artist Valie Export is one of the mothers of feminist media art. In her 1968 work,

Tapp- und Tastkino (“Tap and Touch Cinema”), she redirects our attention from seeing to feeling. For

Tapp- und Tastkino, she placed a box in front of her chest and asked passers-by in Munich to feel her breasts. As in cinema, the female body serves as projective space for male fantasies – with Valie Export’s performance ironically commenting on this.

Rotraut Pape’s short film

Rotron (1982) takes up the critique of representations of masculinity in digital discourses with equal irony. In the US-American virtual reality film

Tron (1982), a human being in a computer system battles against other programs. This inspired Pape to create her short film

Rotron, in which she satirises the heroic narratives of hackers and computer experts with the simplest of means (a bed, helium bottle and telephone).

In a squeakily nasal voice, she plays a computer programme that intends to hack the Pentagon: “There is the world of three dimensions. The world in which the laws of physics are valid. This world is an electronic microcosm that breathes and lives next to us”.

Against disembodiment

Foto: Jens Ziehe © VG Bild-Kunst 2004

Foto: Jens Ziehe © VG Bild-Kunst 2004

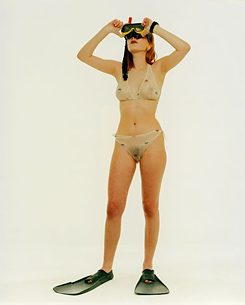

Eva Grubinger’s

Netzbikini of 1995 addresses the internet’s collaborative potential. She makes available patterns and directions on a website and calls upon the users to sew a copy of the bikini - preferably with web fabric. Those who send the artist a photo of the piece of clothing are sent a label in return as "thank you" that designates the bikini as a genuine Grubinger. In this way, Grubinger counters the discourse of digital disembodiment with the physical labour of sewing and putting on clothing.

1997 is an important turning point for web-based art: for the first time, at the documenta art festival that is held every five years in Kassel, web-based works were exhibited within the context of the established art system. Yet again, women were underrepresented. The only women participants, Eva Wohlgemuth and Joan Heemskerk, did not exhibit as solo artists, but jointly with their respective male (art) partners.

Eva Grubinger | Netzbikini, 1995

| Foto: Jens Ziehe © VG Bild-Kunst 2004

Eva Grubinger | Netzbikini, 1995

| Foto: Jens Ziehe © VG Bild-Kunst 2004

Nonetheless, documenta 10 was also the site of the “First Cyberfeminist International”, which was organised by the Old Boys Network

group. About 40 women artists, activists, hackers and theorists from Eastern and Western Europe, Australia and the USA gathered in Kassel to discuss the ways in which the new media were changing gender constructions. The participants debated the underrepresentation of women in this context as well. For many women, this was an important personal validation: we are here and have something to say!

to be a cyborg rather than a goddess

Above all, the Australian women artists’ group VNS Matrix ranks among the pioneers of cyberfeminism. Already in the early 1990’s, they were making use of digital and network metaphors with the intention of infiltrating an interference factor into the sleek technoid surfaces. “We are the future cunt” they proclaimed, and: “The clitoris is a direct line to the matrix”. Their aim was to celebrate corporeality in a medium that had been constructed as incorporeal. VNS Matrix was inspired by theorist Donna Haraway, who wanted to be a cyborg rather than a goddess and advocated an expansion of what it means to be human, one in which binary gender differences were to dissolve.

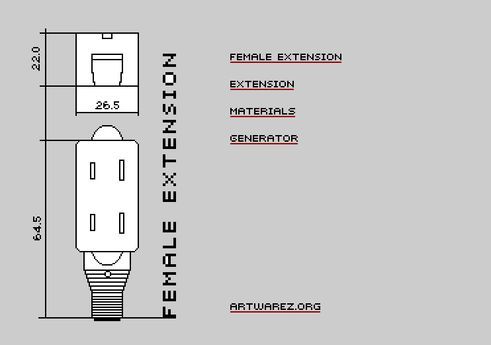

Cornelia Sollfrank | Screenshot of the documentation Website Female Extension (1997): http://artwarez.org/femext/

| © Courtesy Cornelia Sollfrank

Cornelia Sollfrank | Screenshot of the documentation Website Female Extension (1997): http://artwarez.org/femext/

| © Courtesy Cornelia Sollfrank

In 1997, Cornelia Sollfrank’s work

Female extension drew attention to the invisibility of women in web art in Germany in an original fashion. Sollfrank, who was also the initiator of the

Old Boys Network, took a contest by the Hamburger Kunsthalle as the occasion to create 288 virtual female women web artists, complete with names, email addresses and automatically produced artistic works, and to submit “their” works to the contest. The Kunsthalle was delighted by the high participation by women, but the awards went to men. With her hack, Sollfrank made visible the homogeneity of the digital art scene - a state of affairs that to this day has changed only gradually.

Laboria Cuboniks Xenofeminism | Screenshot (01.06.2017)

| © Laboria Cuboniks Xenofeminism

Laboria Cuboniks Xenofeminism | Screenshot (01.06.2017)

| © Laboria Cuboniks Xenofeminism

Laboria Cuboniks might well take up the cyberfeminists’ legacy. In mid-2015, this group of women artists from five different countries issued the

XenoFeminist Manifesto. In it, they speak out, fully in the tradition of Donna Haraway, for a reassessment of the concept of alienation: ”We are all alienated”. In their radical construction of bodies and thinking, this involves a possibility of freedom.

The question of the political meaning of gender has been one of the most important aspects in the work of women web artists. Since the late 1980’s, women artists have answered it in different ways. But in the meanwhile precious little has changed in social structures.