An interview with Van Bo Le-Mentzel

The Trojan horses of systemic change

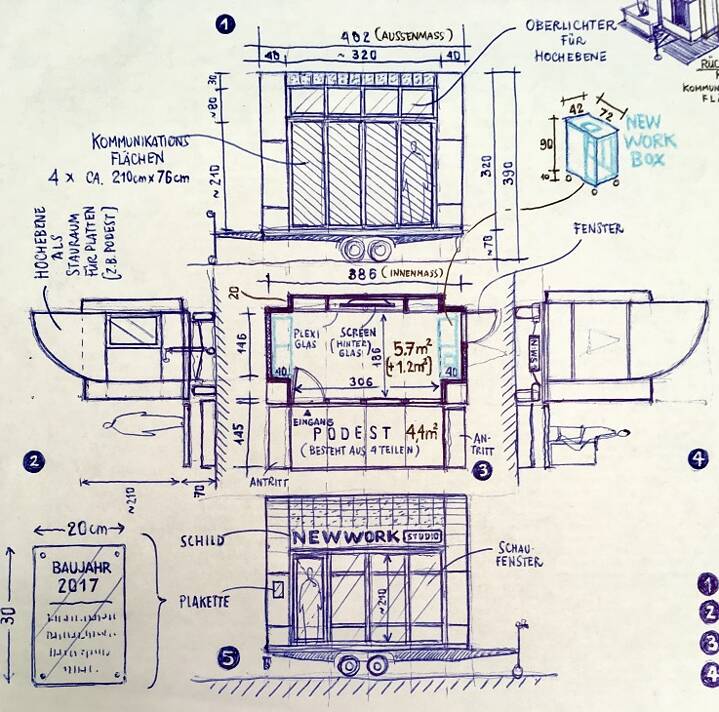

Van Bo Le-Mentzel is an unconventional thinker. The architect became known for his simple and inexpensive self-assembly instructions for Hartz4 wooden furniture. Then he extended the idea of democratic design to dwellings, developing living accommodations on bicycle trailers and tiny houses on wheels.

Recently, Le-Mentzel founded with like-minded people a temporary campus of mini-houses on the grounds of the Bauhaus Archive, a village and utopia that puts up for discussion new concepts of dwelling. When we meet on the site at the beginning of February, some of the houses are being painted and screwed together, groups are gathering for an architectural tour or a planning workshop. Le-Mentzel spends a lot of time here. Still. In March, when construction of Volker Staab’s new building of the museum starts, the Bauhaus campus will have to close.

Van Bo Le-Mentzel, it’s pretty cold, but people are still working everywhere.

Yes, I am amazed myself how much happens here even in freezing winter temperatures. People are committed because they have the opportunity to design things themselves. The Bauhaus campus was a one-year experiment in which we posed the questions: How can fairer cooperation work? How can human beings, who need work, community and space, realize these needs in urban space?

During the day you use the campus for work and workshops; at night some of the tiny houses are overnight shelters for people without a permanent residence. What has the response to this concept been?

The museum was thrilled. The neighbors too – for example, by the vegan food that is now available here. My impression is that we hardly have any enemies. But then we don’t do anything that could be considered bad: we don’t take anything away from anyone, we don’t expropriate anyone. And if people are here around the clock, they create a space of social control and there’s less crime. The museum effectively saves itself a guard.

It’s like this: in Germany, dwelling is fundamentally prohibited. If you own a plot of land somewhere, you are only allowed to spend the night there occasionally. Your primary residence is not allowed be a hotel, school, gym, truck or museum. There’s only one exception to the German ban on dwelling: a flat.

And you see this as a problem?

Not to have a residence means in Germany not to exist. You don’t get a tax number or a bank account. For example, we have someone from Kurdistan here who has no papers because Kurdistan doesn’t exist legally. Why does he have to adapt to our norms? If the office of public order came by, however, and we told them something about the philosophy of borders, we’d be talking to the wrong people. That’s why we say: it’s all art. And research.

Do you see yourself as an architect, artist or researcher?

I’m the court jester. I know that people think the houses are cute. With their small verandas and wooden façades, they look like a cozy Finnish sauna. But these are Trojan horses with a very serious content. It’s about homelessness, about system change, about transformation processes in society. What does a world look like in which we no longer separate dwelling and working? How can we deal with public resources, with town halls or schools that are unused at night?

Not many places so far have been converted for new use. What needs to change?

My idea for tiny houses is a parking permit that allows them to be parked anywhere in the city. By this I don’t mean that anyone who happens to have 50,000 euros for a tiny house can park where he wants. Rather those who are engaged in projects for the good of society – tutoring, childcare, food sharing, libraries or neighborhood cinemas – should find spaces.

So you don’t see tiny houses as an answer to housing shortages and rising rents?

The basic idea maybe. But a trailer standing in the exhaust fumes on the street is no alternative to a normal flat. Yet a supplement. A space satellite, like a garage. A buffer zone between completely private and completely public, where exactly for this reason something else happens than in the office or the flat. I see the tiny houses as a bridge between very hard uses and potential spaces.

What’s next for you when you have to leave the present grounds?

We don’t want to lay down roots. That’s why the trailers on which the tiny houses sit are a beautiful metaphor: we hitch ourselves to the neighborhood, to the infrastructure. Our project isn’t made for the desert; it docks onto the urban space where we find swimming pools, toilets, electricity, water connections and the services of public buildings – everything we need to live in the tiny houses. There are many such places.

What did you learn in the last year?

I learned a lot about freedom. And that it has to with space only to a limited degree.

How do you live yourself?

I live with my wife and two children in a 56 square meter flat. We deal with the space intelligently. It’s like this: we don’t have too little living space, we have too little imagination.

Comments

Comment