Language – unique to humans

People learn languages especially well from the age of approximately one year to puberty. After that, the ability to learn languages gradually declines. But even adults can still learn a new language very well if they really want to – scientific studies have shown this.

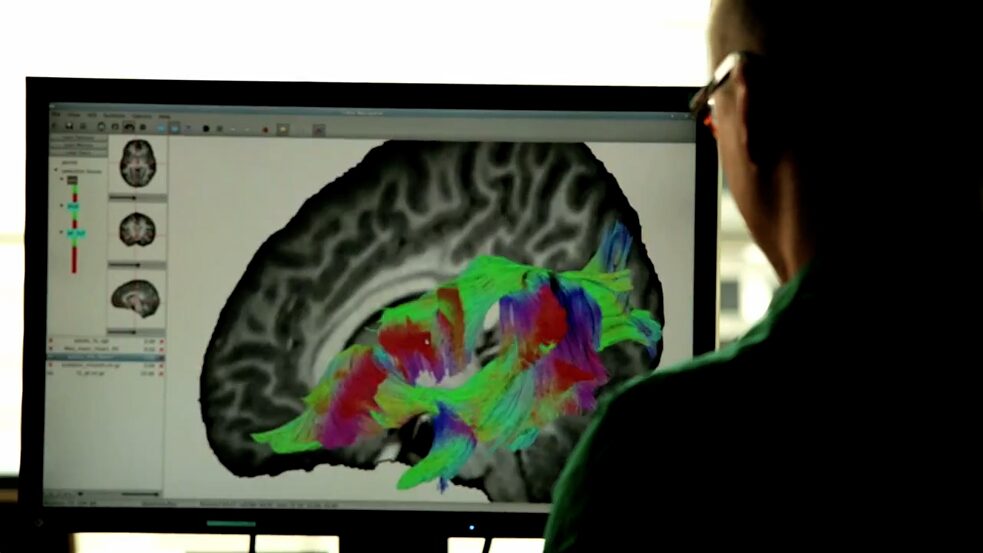

To process language, several brain areas have to work closely together. Some are important for sentence construction or grammar, others for the meaning of the words. This can be easily observed in infants: the nerve bundles that connect the different brain areas together like data highways only develop gradually. That’s why children can only gradually begin to understand complex sentences or produce these themselves.. The pace of learning varies: while some children say their first words as early as eight months, others only start talking from the age of two years.

Language is what makes us human

For Angela Friederici, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, language is what makes us human. Some animals, such as apes or even dogs, can learn the meaning of individual words – but connecting language together logically and on the basis of fixed rules is something only humans can do. Friederici and her team primarily analysed how the brain matures, which plays a key role in language development. The thing is, the individual brain areas responsible for language develop at different rates. Up to the age of three, a region known as the Wernicke region (language comprehension) in the temporal lobe predominates asthe language centre. It’s only then that the second central language region comes into play as well: the Broca’s area (language production) in the forehead area of the cerebrum. Now it is possible to construct increasingly complicated and meaningful sentences. But many years are needed until the connections between the two areas are fully developed. It isn’t until the end of puberty that we can process complicated phrases as fast as simple ones.

Language is what makes us human

For Angela Friederici, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, language is what makes us human. Some animals, such as apes or even dogs, can learn the meaning of individual words – but connecting language together logically and on the basis of fixed rules is something only humans can do. Friederici and her team primarily analysed how the brain matures, which plays a key role in language development. The thing is, the individual brain areas responsible for language develop at different rates. Up to the age of three, a region known as the Wernicke region (language comprehension) in the temporal lobe predominates asthe language centre. It’s only then that the second central language region comes into play as well: the Broca’s area (language production) in the forehead area of the cerebrum. Now it is possible to construct increasingly complicated and meaningful sentences. But many years are needed until the connections between the two areas are fully developed. It isn’t until the end of puberty that we can process complicated phrases as fast as simple ones.

Music and language have a lot in common. For neuropsychologist Daniela Sammler of the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, this is demonstrated for instance when a mother sings a song to her baby or talks to them in a certain way. The child understands the emotions communicated through this melody. Much like language, music in every culture also has a set sequence of sounds and – like a “grammar”. If musicians infringe these rules, similar areas of the brain are activated as for a grammatical error in a sentence.

With language and music, humans have developed two types of communication that no other living creature has. Daniela Sammler is convinced that the reason for this is the way information is processed by the brain. So her research group is exploring the meaning of language melody in our communication and also the way we perceive melodies in music.

A pianist plays a piano developed especially for this purpose whilst lying in an MRI unit. The scientist can observe his playing and his brain activity.

Language is in our genes

Some people are good at expressing themselves through language and learn foreign languages easily. Others find it far more difficult. It also depends on the environment, but the pre-requisite for language and speech is found in our DNA. The gene FOXP2, which was discovered in 1998 by Simon Fisher and is often referred to as the “language gene”, plays a key role. But it isn’t the sole condition for language, because FOXP2 is also present in monkeys, rodents, birds and even fish. Today it is known that FOXP2 is what we call a transcription factor. It regulates the activity of up to 1000 other genes in a neurobiological network. So there is not an individual “language gene” – language is highly complex, at a genetic level as well. For this reason the researchers in Fisher’s department at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics want to decode the genetic and neurobiological networks that make language and speech possible.

Cooperation partners

|

|