The Elite in the Arts | Visual Arts

Defining Photography

Since its birth, creative photography has experienced a very bumpy path, fighting to become an independent art form.

While the basic steps to capture and make permanent an image were given freely to the world by the French government in 1839, the process proved to be arcane and difficult, requiring great skill. And there was a serious complication: the procedure demanded developing light sensitive silver plates over the fumes of mercury, slowly poisoning its practitioners.

From those very first years, photography stood accused of being incapable of being a fine art because it was made by a machine, the camera. By the turn of the century, the process had been made safe and also vastly simplified. Cameras became affordable and plentiful worldwide. Photography boomed as a hobby and camera clubs were everywhere. Photographers did not even have to develop film or print negatives. Anyone could make a picture, declared the Kodak ad: "You push the button. We do the rest."

For the first third of the twentieth century, most photographers adopted a style called Pictorialism in which photographs were made to replicate the look of established art forms. Soft-focus lenses, matte-textured and brown-toned printing papers, manipulation of the negative’s light-sensitive emulsion, romantic lighting, deliberate simplification of detail—many different effects were used in the effort to make a photograph look like a charcoal or an etching, or pastel drawing, manipulative techniques to show the hand of man overpowering the apparent machine, so that photography could be considered art. In addition, pseudo-historical subject matter became a popular subject to communicate the serious purpose of the photographer.

As a young man, American Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) studied photochemistry in Germany and gained prominence in photographic circles there by winning prizes at various salons and exhibitions. He returned home and became a leader of the Camera Club of New York. Stieglitz rejected Pictorialism, including the popular soft-focus lens, and chose instead lenses capable of sharp focus. He preferred natural light to the traditional artificial studio lighting. His viewfinder framed uncontrived, natural compositions in the city streets. His goals were to promote photography as a respected and independent medium: his vision of photography was art. Stieglitz opened a succession of hugely influential New York art galleries. While he exhibited photographs, paintings, and sculpture over the next four decades, covering the first half of the twentieth century, he found but a handful of photographers to be worthy of his support. It can be said that during his lifetime he was the most powerful leader in photograpy in the world. But he nurtured an atmosphere of exclusivity. He represented only artists who figuratively knelt before him. He charged his clients premium prices and would sell only to those he deemed worthy. He cultivated a new sensibility that eschewed Pictorialism but embraced elitism.

In 1932, an American photography movement, Group f.64, determined to set its own course, establishing photography as a fine art without Stieglitz’s exclusionary practices, including gender equality. Unable to gain recognition by Stieglitz, members of Group f.64 judged him to be out of touch with reality, with the contemporary world. They were exclusive only in their shared beliefs. They also agreed that photography must be wrested from the Pictorialists once and for all. Together they pledged to forge their own identity, separate from and in contrast with Stieglitz’s approach.

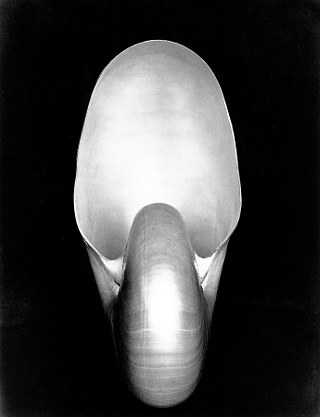

Group f.64 named itself for a tiny aperture setting on view camera lenses: focal length, f.64. A small lens opening combined with long-enough exposure time yielded the finely focused image with great depth of field that they demanded in their prints. Photography is the medium of light—light focused by a lens. Photography is capable of producing an image of exquisite sharpness of detail, with great depth-of-field, and a full range of tonalities. Photography can be an expression of immediacy. It can capture the world as it is seen and expressed by the photographer (although not necessarily as it really exists).

Most likely Group f.64 was the first art movement created at its very inception by both women and men. The members came from all walks of life. Three were college students, two were studio portrait photographers, one was a failed classical pianist, others were a housewife, a banker, a department store manager, a photographic assistant, and a newspaper photographer. All worked in their spare time to express themselves as creative artists, as creative photographers.

To promote their philosophy they decided they must take their plan for photography to the masses. In the tradition of the other avant-garde movements of that century, they wrote a manifesto to proclaim publicly their beliefs and chart a plan of action. They posted it on the wall of their first museum exhibition in November 1932 at San Francisco’s M.H. de Young Memorial Museum.

They knew that not only the example of their photographs but also education would be the key to their crusade. That meant writing books and magazine articles. That meant teaching workshops and establishing schools and departments of photography at universities and museums. They did all these things: Making a Photograph, a basic textbook on how to create a finely focused negative and a sharp print from that negative (1935); the first Department of Photography in a museum—the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), NY (1940); and the first Department of Photography (as a creative art) at a college degree granting institution—San Francisco Art Institute (1945).[“Making a Photograph,” excerpt or?; Picture of MoMA Department of Photography reading room, 1942; William Heick, “Guest Instructor Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams Discussing Photographs by Lisette Model with Students,” 1948; Al Richter, “Edward Weston Pointing Out Rock Formations to a Group of Students at Point Lobos,” 1948.

They made it clear that photography’s true strengths could be applied to the complete panorama of photographic expression. Who were these photographers? What were their contributions? Some would become among the greatest artists of their time.